State Capacity and Climate Change Adaptation in Nepal

By Rohini Pande, Michael Callen, Jenna Allard, Gauri Shankar Gautam, Juni Singh and Chandra Bhandari

Executive Summary

- LGs have not fully fulfilled their climate responsibilities, and struggle to report budget allocations on climate risk resilience and disaster management.

- Local politicians overestimate their knowledge of climate change, and actual levels of knowledge are low.

- Politicians report that they see climate change as a major issue, but they believe that their constituents would prioritize development.

Context and Sample

Globally, climate change is a major threat to wellbeing, social inequality, and economic growth. Yet solving the climate crisis is inextricably linked to politics and redistribution. Nepal ranks 135 out of 185 countries on climate vulnerability, but its carbon emissions are only 0.1 kg per PPP $ of GDP. Effective climate justice will require supporting Nepal’s local governments to implement effective adaptation policies.

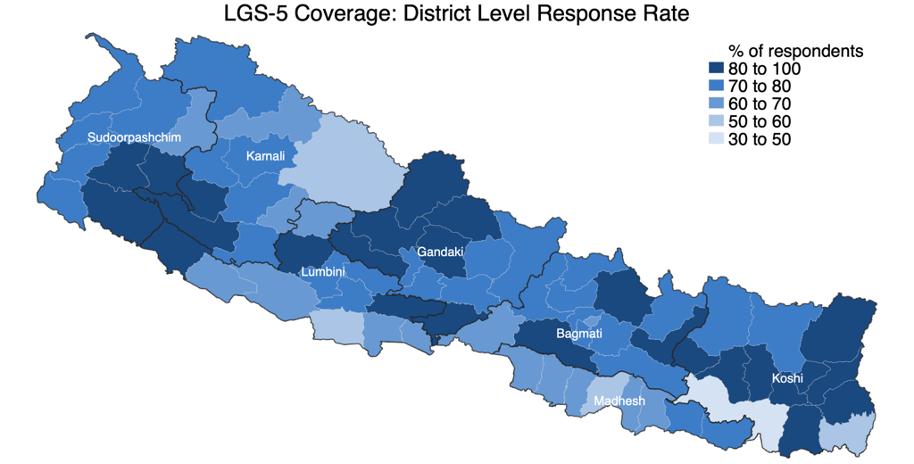

From February to March 2023, we conducted surveys with 12,251 local and ward-level officials across 95% of LGs in Nepal to understand how local elected officials perceive their own climate responsibility, and whether their actions on climate change are limited by knowledge or by perceived political risks.

Although local officials recognize that climate change poses a significant risk to their municipalities, many have not taken significant action to address its impacts. Our data reveals two potential channels to limit this action: (i) limited knowledge of climate change impacts and how adaptation can be linked to local policies, (ii) a perception that climate is a low priority among their constituents, suggesting that it may not be a vote-winning issue.

Below, we describe the main findings of our survey.

Finding 1: LGs have not fully fulfilled their climate responsibilities, and struggle to report budget allocations on climate risk resilience and disaster management.

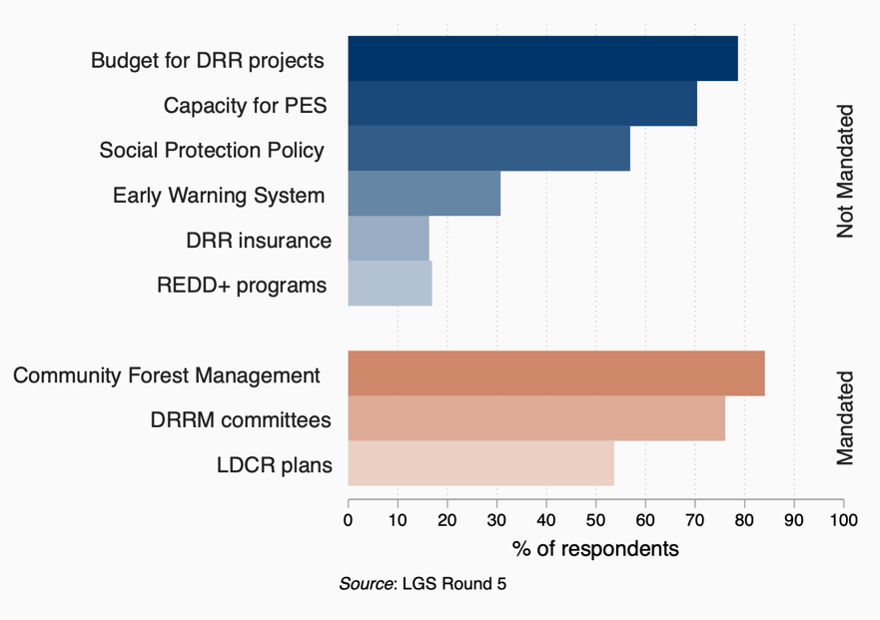

27% of LGs have not yet formed a constitutionally mandated Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM) committee. While 84% of LGs have kept up with managing long standing activities like community forests management, most LGs have not participated in REDD+ schemes, put Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) insurance in place or set up early warning systems (see Figure 1).

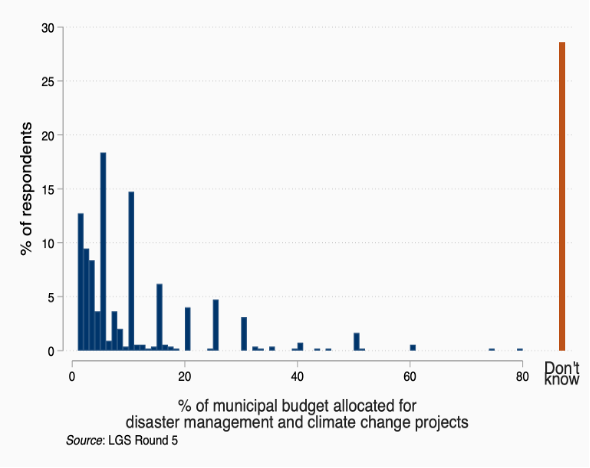

Figure 2 reports that close to 30% of the local officials do not know if their LG has allocated a budget for climate action. About 12% of the LGs have not allocated any budget toward climate action. More than 25% of the LGs have less than 5% budget allocated to climate adaptation policies.

Finding 2: Local politicians overestimate their knowledge of climate change, and actual levels of knowledge are low.

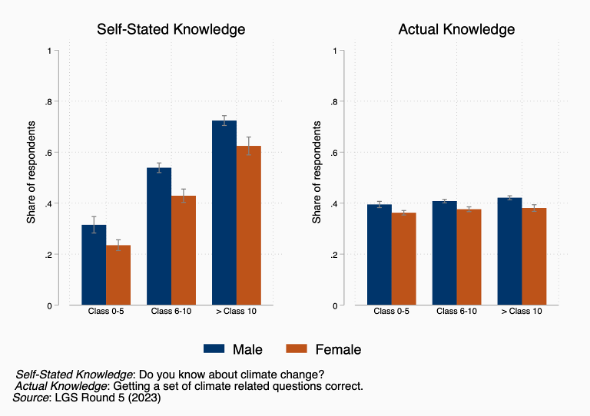

Local politicians overestimate their climate knowledge. This is especially true in the case of male and high-educated politicians. On average 50% of the politicians reported having moderate to high levels of climate knowledge. But in comparison, only 39% managed to answer climate related questions correctly (see Figure 3).

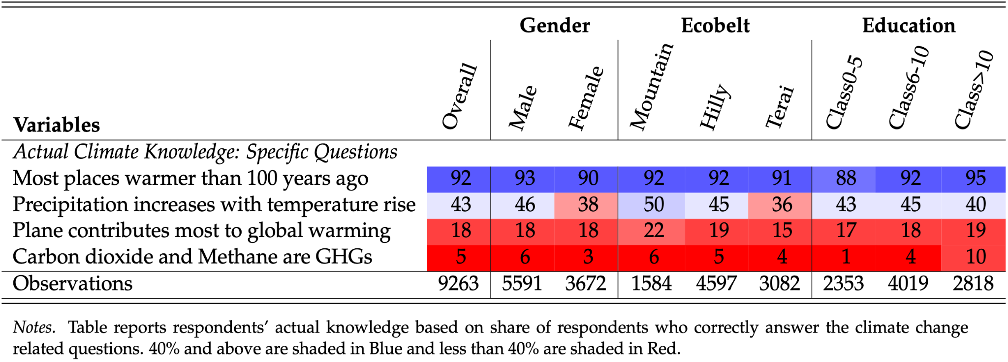

Table 1 shows the accuracy rates for different climate related questions in the survey. Local politicians are aware about climate change as evidenced by high accuracy in the question that asks if global temperature has risen in the past 100 years. However, accuracy drops as we ask about the specifics of climate change which reveals overall low climate knowledge.

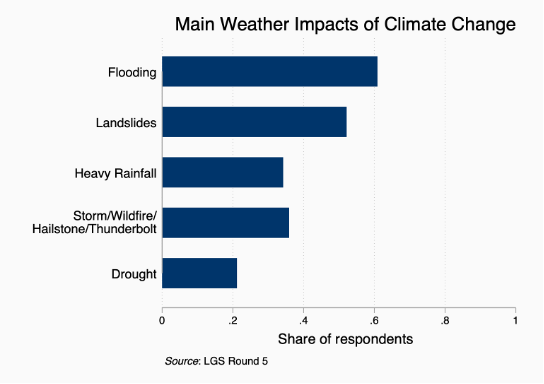

Figure 4 shows that flooding (60% of the time) is mentioned as the main impact of climate change followed by landslides (38% of the time). It is interesting that both these phenomena are precipitation based, yet there is there is a considerably low accuracy in the precipitation question as shown in Table 1. Local politicians do recognize that they are confronted with major weather impacts due to climate change but lack an understanding of the intricacies of climate change to make informed decisions.

Finding 3: Politicians report that they see climate change as a major issue, but they believe that their constituents would prioritize development over environment.

73% of local officials believe that they are responsible for tackling climate change, and 64% see it as a lot more serious issue, and 29% see it as a moderately serious issue.

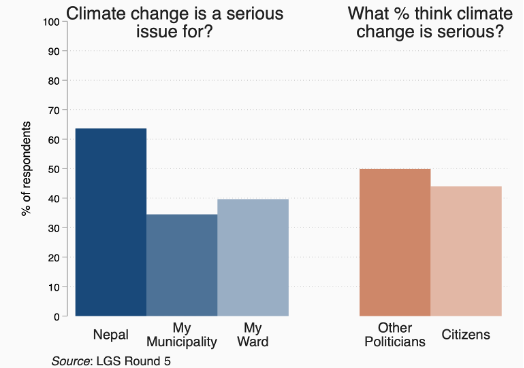

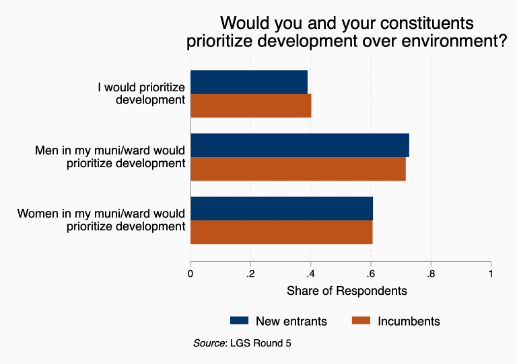

While the majority of politicians say they would prioritize the environment over development, they report that their constituents would instead prioritize development (see Figure 5). 64% local representatives believe that climate change is a serious issue in Nepal, they believe that only 50% of other local politicians and 40% of their constituents are serious about climate change (see Figure 6). Only 35% of local politicians believe that climate change is a serious issue for their own municipality or ward, and they do not list climate change in their top three policy priorities. Local representatives rank climate change 4th below education, roads and infrastructure and health.

Implications

Local Governments are not fulfilling their mandate to reduce climate risk. Our findings suggest the need to build basic knowledge among local politician on the implications of climate change for their constituencies, particularly with regard to extreme weather events and precipitation patterns. We also suggest building a concrete link between climate risks and local adaptation plans. In addition, we need to understand whether politicians are correctly understanding citizens’ perceptions on the value of addressing climate change, so we can suggest interventions to make adaptation policies more politically viable and salient at the local level.

Appendix