In the US-China trade war, how did some “bystander” countries come out ahead?

Recent years have seen globalization evolve in response to shifting trade dynamics and increasing geopolitical uncertainties – including, since 2018, a trade war between the world’s two largest economies. Rather than triggering an overall decline in global trade, however, these trends are transforming global trade patterns. Most notably, trade is reorienting away from the United States and China as other nations adapt to emerging opportunities and challenges. What are the key dynamics and broader implications for these “bystander” countries to the US-China trade war?

New research by EGC affiliates Pinelopi (Penny) Koujianou Goldberg and Amit Khandelwal (with coauthors) in the American Economic Review: Insights explores these issues and their ripple effects. Analyzing recent global trade data, their study reveals how bystander countries have seized opportunities during the trade war to boost their global exports of goods subject to tariffs by the United States and China. Most notably, they find that countries with exports that are substitutes for products targeted by US and Chinese tariffs saw significant growth – particularly countries with greater ability to rapidly boost production in those products – while countries with complementary exports saw smaller gains. The study highlights that despite increased trade uncertainty during the trade war, global trade did not collapse; it shifted from the United States and China to other countries, signaling a transformation in globalization rather than its end.

During the US-China trade war, the rise in exports of tariffed goods by "bystander" countries was large enough to offset the collapse of trade between the United States and China.

On average, exports of tariffed goods from bystander countries increased to the US, changed only marginally to China, and increased to the rest of the world – resulting in a net increase in trade, rather than just shifting trade across destinations.

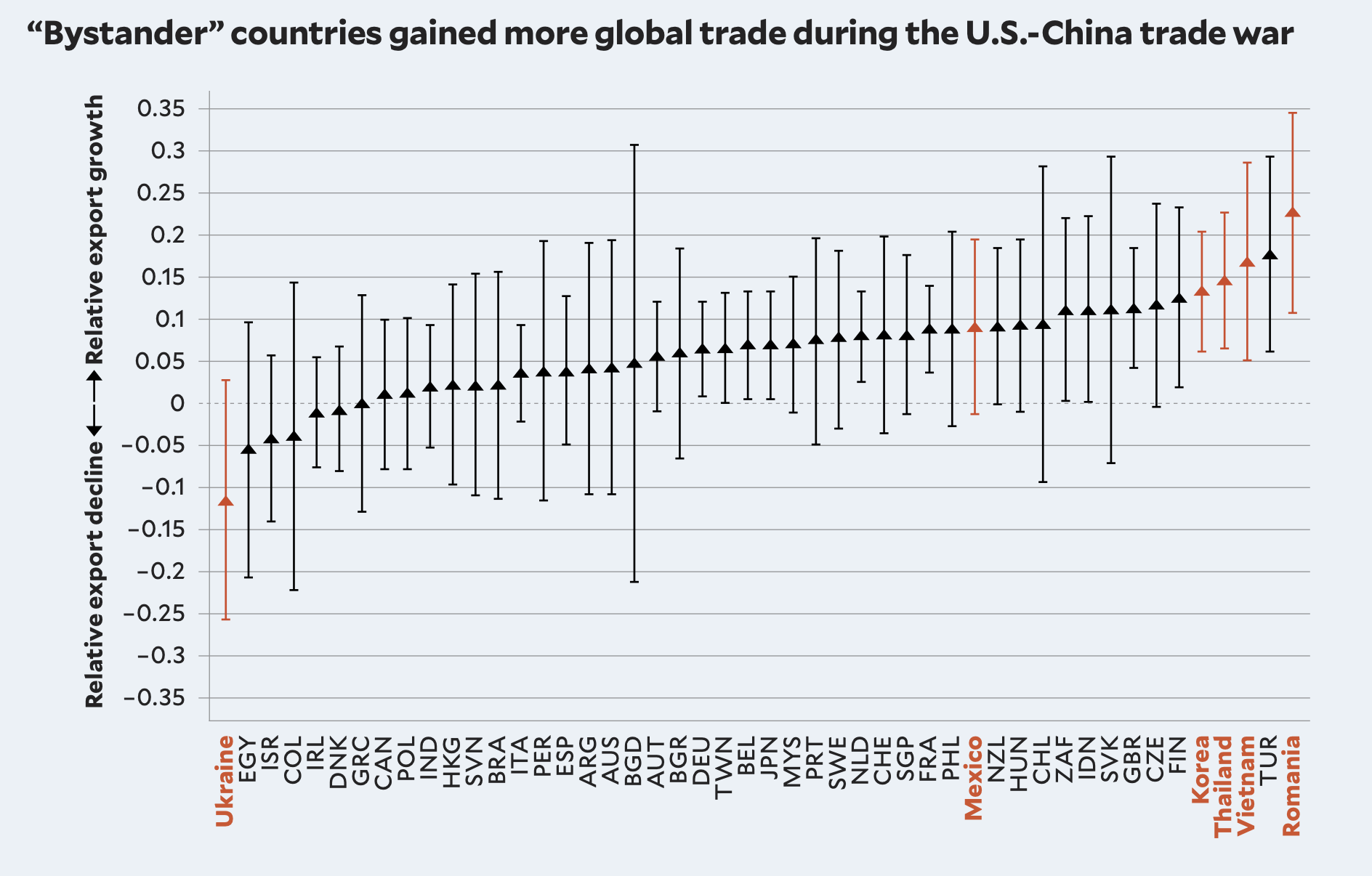

Export growth in targeted products varied significantly across countries, with countries like Vietnam, Thailand, Korea, and Mexico emerging as major beneficiaries.

Differences across countries and sectors in export growth for targeted products are mostly due to supply elasticities (or the ability to rapidly boost production of specific products in response to tariffs), along with the size of trade flows and pre-war specialization patterns.

Of these factors, an estimated 75.8 percent of the variation in export growth across countries was driven by country-specific factors.

Tensions for some, opportunities for others

In 2018 and 2019, the United States and China sparked a trade war by imposing tariffs on approximately $450 billion worth of goods. This disrupted the decades-long trend toward reduced global trade barriers and notably decreased direct trade between the two countries, a trend that continues today. However, the conflict also created unexpected opportunities for bystander countries not directly involved in the US-China conflict, many of which seized the opportunity to by boost their exports of the tariffed products to the US, China, and other markets.

Which bystander countries benefited from the US-China trade war, why, and how? In our globally connected world, the answers to these questions depend on a complex interplay of trade dynamics and economic forces. In their new study, Penny Goldberg, the Elihu Professor of Economics and Global Affairs, and Amit Khandelwal, the Dong-Soo Hahn Professor of Global Affairs and Economics – along with coauthors Pablo Fajgelbaum, Patrick Kennedy, and Daria Taglioni – shed light on these issues, analyzing detailed trade data to investigate the ways in which some bystander countries benefited from the US-China trade war.

“When the US-China trade tensions escalated, some countries were euphoric because they thought, this is our chance,” Goldberg said in an EGC interview. “We can actually fill the space, the void left by China. So there was this incredible optimism among some, among others, that was great anxiety.”

Modeling a trade war

To conduct their analysis, Goldberg, Khandelwal, and their coauthors began by developing an economic model to better understand how the complex dynamics of global trade were affected by the US-China trade war. On the demand side of the model, they estimated how global demand for a large number of traded goods was influenced by the imposition of tariffs – which depends on factors like prices and whether a particular good is a substitute or complement for the products targeted by US and China tariffs. On the supply side, the model incorporates trade costs and tariffs for each exporting country and tariffed product. This setup made it possible to estimate bystander countries’ export responses to US and Chinese tariffs.

To build and refine their model, the researchers analyzed more than 5,000 product categories using UN Comtrade data from 2014 to 2019, a period that straddled the onset of the US-China trade war. They focused their analysis on major exporting countries (excluding oil exporters). Once exports from the US and China were excluded, the dataset covered approximately 71% of all non-oil global trade. Then they examined export trends to three destination categories – the US, China, and all other countries – across nine sectors: agriculture, apparel, chemicals, materials, machinery, metals, minerals, transport, and “miscellaneous.”

The authors’ tariff data reflected substantial country and sectoral variation following the onset of the trade war in 2018. The US raised tariffs significantly on Chinese machinery and metals, for example, and China raised tariffs on the US across a number of sectors – while reducing them for non-US partners.

Main findings

At a high level, one of the study’s key findings was that the US-China trade war's impacts on bystander countries hinged on whether a country’s exports acted as substitutes for (i.e., interchangeable) or complements to (i.e., used together with) the products targeted by US and Chinese tariffs. Also important was the concept of “supply elasticity” – or how quickly countries could expand production of the tariffed products. Countries with substitute exports and the capability to rapidly increase production of those substitutes saw substantial export growth, whereas countries with complementary exports saw smaller gains.

These dynamics show up in the trade data. On average, the researchers find that bystander countries increased their exports in tariffed products by 6.4 percent – and the rise in their global exports was large enough to offset the collapse of trade between the United States and China. On average, bystanders increased their exports to the United States, barely changed their exports to China, and increased their exports to the rest of the world in products with higher US-Chinese tariffs. These results show that the trade war created new trade opportunities for many countries, rather than just shifting existing trade around.

There was substantial cross-country variation, however. Countries like Mexico and Thailand, for example, benefited because they already exported products that could replace Chinese exports to the US. But in addition to having this pre-existing specialization, they also had the ability to rapidly expand production of those goods to meet increased US demand after the tariffs were imposed. Conversely, the exports from countries like Colombia and Ukraine were complements to the tariffed products – so they did not see as many benefits.

According to the researchers’ analysis, 75.8 percent of these cross-country differences in how bystander countries benefited from the US-China trade war were primarily driven by these country-specific aspects, rather than pre-existing sectoral specialization or trade flow volumes. This suggests that individual country characteristics played a more significant role than sector-specific or size-related factors in explaining how countries adapted to the trade war.

“We aggregate the two together to come up with an overall winners and losers' picture for each country, which is kind of a weighted average of their export response to the US and China and the export response to the rest of the world,” Khandelwal said in an EGC interview.

Julia Luckett.

Julia Luckett.

Goldberg (second from left) and Khandelwal (far right) with fellow members of EGC's Markets & Development initiative, Lauren Falcao Bergquist and Nicholas Ryan.

US-China tariffs and beyond

Goldberg, Khandelwal, and their coauthors’ study offers a nuanced understanding of how tariffs between major economies can ripple through global trade networks – affecting bilateral trade as well as global supply chains, while also creating new opportunities for bystander countries. Trade did not collapse due to the US-China trade war; instead, it shifted away from the economic super-powers to other countries that seized the chance to boost their global presence.

While benefiting from increased trade, however, these bystander countries – and the entire global economy – have also faced heightened uncertainty and anxiety from the elevated trade tensions. Amid rising protectionism in many of the world’s leading economies, this uncertainty and anxiety poses real risks. In particular, bystander countries often fear that they could be the next targets of tariffs and have become less certain of how reliable the global trading system is.

“It's relevant to two literatures: the literature on trade and how trade policy, how trade protection affects trade flows, but it also speaks to this emerging literature on geopolitics, the tensions between the US and China, and how this is going to affect the rest of the world,” Goldberg said.

Nonetheless, the implication is that recent trends may not signify the end of globalization but rather the onset of a different kind of globalization. The globalized world is adapting to shifting geopolitical forces, resulting in the emergence of new trade partnerships and growing export volumes from smaller economies.

Research Summary by Adam Walker. The cover image shows Cat Lai international port, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam on April 16, 2024. Photo by Tieu Bao Truong, Shutterstock.