Unequal treatment of men and women by economic law: Global trends

Legal gender discrimination, or the unequal treatment of men and women by the law, is one of the most prominent forms of economic gender discrimination around the globe. Using the World Bank Women, Business, and the Law Index, EGC affiliate Pinelopi Goldberg and coauthors Marie Hyland of the World Bank and Simeon Djankov of the London School of Economics and the Peterson Institute of International Economics determined five overarching themes regarding the legal status of women in the workplace.

A woman in the average country has three quarters the rights of a man.

Women are most severely penalized when it comes to laws that are related to having children and getting equal pay.

The last five decades have seen tremendous progress, but the pace of reform has differed across regions.

The pace of reform varies not only across countries, but also across the individual indicators.

Legal gender equality is positively correlated with women’s outcomes in the labor market.

Legal gender discrimination takes many forms. Women are barred from entry into certain professions in many countries, and the law does not mandate equal pay for men and women. Not only does the law, or a lack thereof, directly affect a woman’s work environment, but it also permeates other spheres of her life, including her marriage and her parenting, which may negatively impact her ability to work.

By 2010, many individual studies of gendered laws’ effects on economic outcomes had already been published. However, the existing literature lacked a broader survey of regional variations in women’s legal statuses and of trends over time. To fill this knowledge gap, the World Bank created a database used to construct the Women, Business, and the Law Index, that quantifies global trends in legal gender economic discrimination and is updated annually. It contains data from the last 50 years beginning in 1970.

In the dataset, each country receives a score out of 100 for eight indicator variables. The indicators encompass national laws affecting a woman’s Mobility (the ability to travel independently including the right to choose where to live), Workplace (the ability to get a job and protections from discrimination in the workplace), Pay (the right to equal pay and whether any work-related restrictions exist on women), Marriage (regarding a woman’s relationship with her husband including a woman’s right to divorce and remarry), Parenthood (the ability to work after having children), Entrepreneurship (a woman’s ability to start a business), Assets (the right to property and the ownership of other assets), and Pensions (differentiated retirement age requirements and whether maternal leave is negatively factored into pension pay). A score of 100 indicates that women receive 100% of the legal rights that men enjoy.

Drawing from two sets of WBL country scores, one unweighted and one weighted by population, the researchers identified these trends:

Fact #1: A woman in the average country has three quarters the rights of a man.

In 2019, the global average of WBL scores was 75.2 unweighted and 74.4 when weighted by population, meaning the average woman receives only three quarters the legal rights as her male counterpart. As expected, this statistic varies widely by region, with a remarkably high average across the OECD countries (94.7) and with the lowest scores found in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region (49.6). Eight countries, including Belgium, Canada, and Denmark, received a WBL score of 100 while countries like South Sudan and the Republic of Yemen scored under 30.

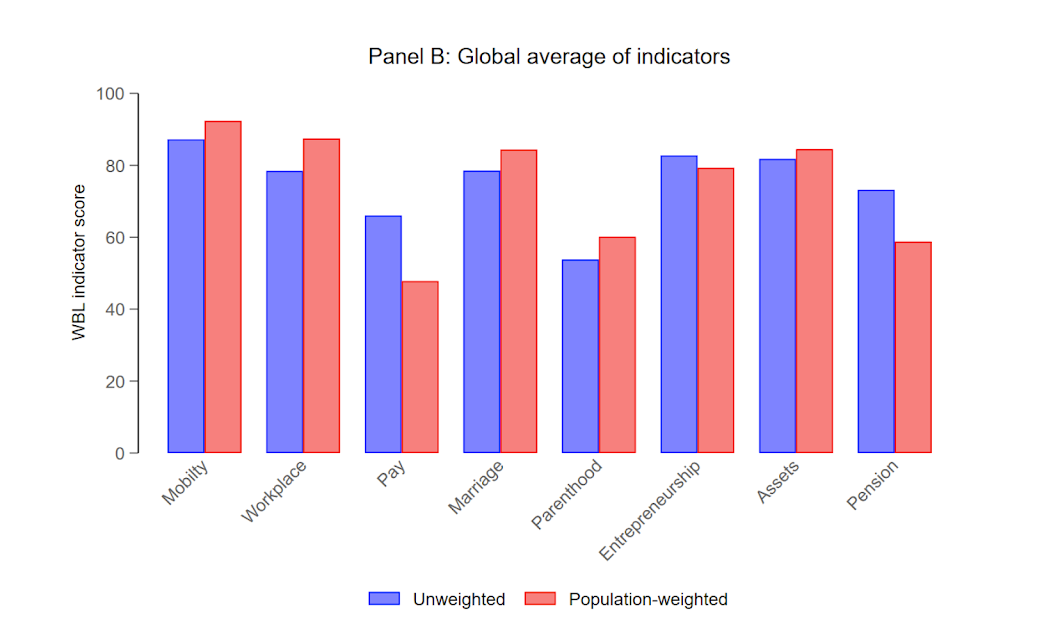

Fact #2: Women are most severely penalized when it comes to laws that are related to having children and getting paid.

Drawn from Figure 1 in working paper

Across the board, women experienced the least restrictions on their ability to travel independently. On the other hand, the researchers found that women experienced the most discrimination regarding their reproductive rights when examining the unweighted WBL scores. When they looked at population-weighted scores, they found that women experience the most discrimination when they are being paid. To explain these differences, the authors point to China and India, which both scored 25 out of 100 on the Payment indicator.

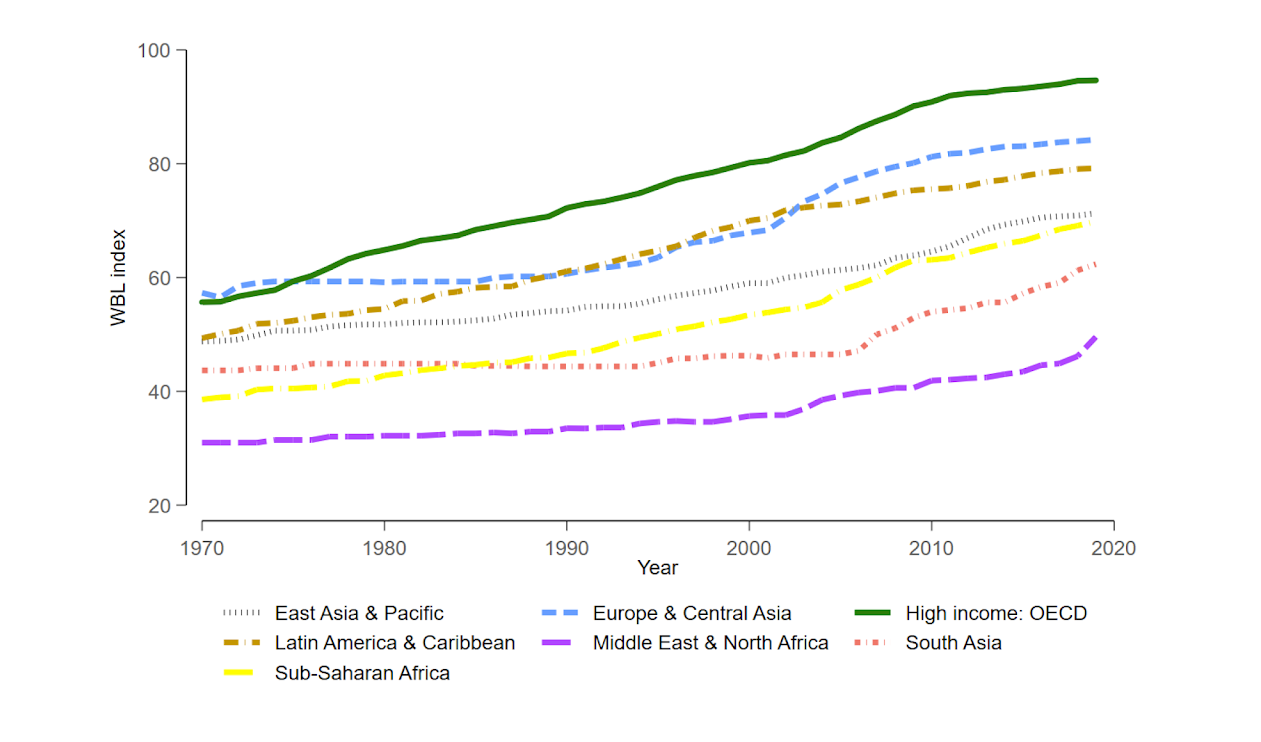

Fact #3: The last five decades have seen tremendous progress, but the pace of reform has differed across regions.

Charting the progress of legal gender equality over time. Drawn from Figure 2 in working paper.

The global average WBL score has increased from 46.5 in 2970 to 75.2 in 2019. However, the aggregate data obscures differences in pace of reform in different regions. For example, the Latin America & Caribbean (LAC) region of the world had a very similar WBL score to East Asia & Pacific (EAP) in 1970, but LAC countries have since outpaced their EAP counterparts in gender workplace reform. The researchers believe that LAC progress towards gender workplace equality was heavily influenced by early European reform movements of the same nature.

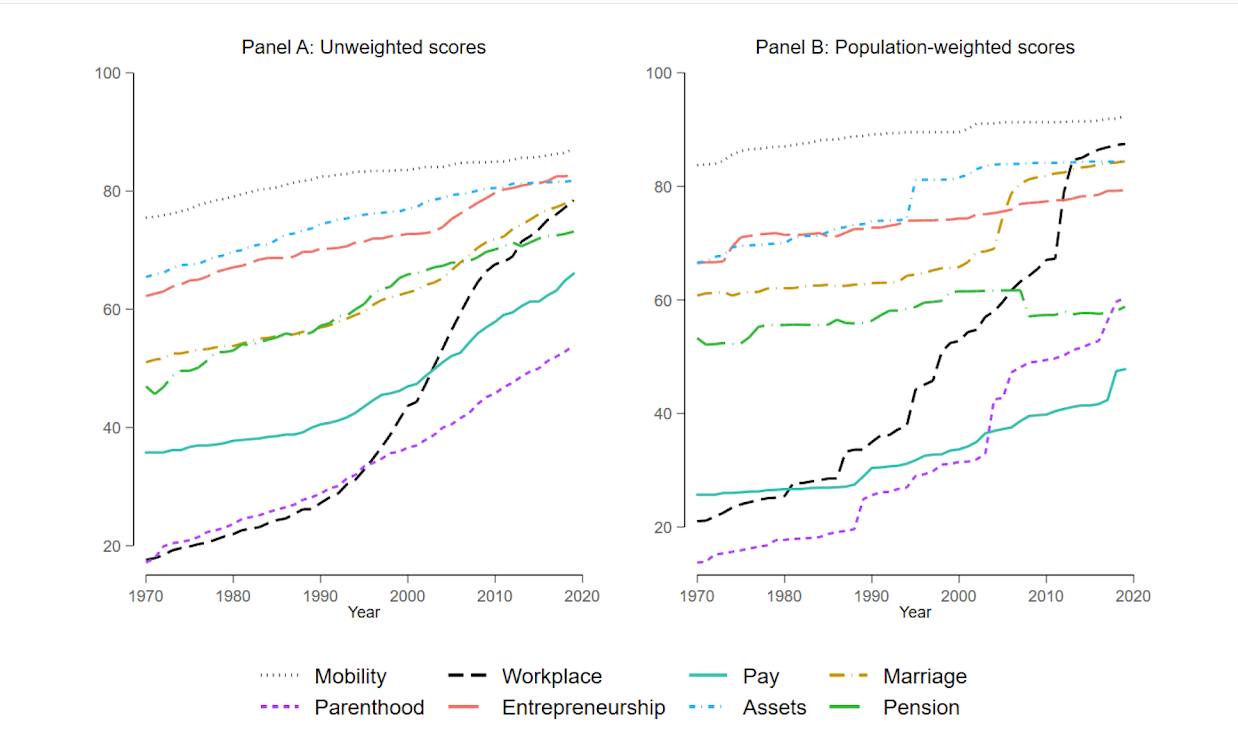

Fact #4: The pace of reform varies not only across countries, but also across the individual indicators.

Drawn from Figure 5 in working paper.

Of all the indicators, Workplace-related laws were reformed at the most rapid pace, whereas laws regarding Mobility experienced a rather slow pace of reform. Interestingly, when weighted by population, improvements in Pension related laws actually regressed around 2008 when China mandated different retirement ages for men and women.

Fact #5: Legal gender equality is positively correlated with women’s outcomes in the labor market.

The authors found that a higher WBL index score correlates with better outcomes for women in the labor market as measured by the gender wage gap and by female participation in the non-agricultural sector (since agricultural work is often informal and therefore not regulated by the law).

The Pace of Change

From the data, the researchers postulate that economic motives underlie the differing pace of legal reforms across indicators. For instance, laws that increase the female labor participation rate often pass much quicker than laws that guarantee equal pay, perhaps coinciding with periods of rising labor demands.

While the authors draw many important conclusions from this dataset, they also note the WBL is not without any limitations. Since these laws were evaluated at the national level, it is possible that this dataset obscures any regional discrimination among other marginalized groups.

Furthermore, the WBL cannot paint a full picture of gendered economic discrimination by exclusively analyzing the de jure legal infrastructure and ignoring the de facto of sociocultural norms and environmental pressures. But we have reasons to be hopeful: Recent research on the relationship between laws and norms outlines cases in Senegal, India, and Cote D'Ivoire where changes in the law have successfully improved economic outcomes for women. Thus, relative improvements in regional WBL indices might establish greater female economic empowerment, now and in the future.

Research summary by Sarah Guan.