Assistant Professor Diana Van Patten on the surprising impacts of foreign firms in Costa Rica

Political scientists define banana republics as politically unstable nations that economically rely on the exportation of a single product. In Honduras, Guatemala, and other Central and South American nations, this product was bananas grown by the American United Fruit Company; the firm’s monopoly led to extreme class stratification and exploitative labor practices in those countries. But Diana Van Patten – whose appointment as Assistant Professor of Economics at Yale School of Management and an EGC affiliate begins this Fall – made a surprising finding in a new paper: the presence of a monopolistic foreign firm in Costa Rica during the late 20th century had long-term positive impacts on its workers. The paper is one of several in her line of research on the long-term effects of the presence of foreign firms in Costa Rica.

Van Patten’s interest in Costa Rica is two-fold: she was born and raised there, and also sees potential in the unique opportunities the nation provides for research. “There are natural experiments and data that allow you to answer unusual and interesting questions,” she said.

Watch an Econimate explainer video of this research

An animated film "Do Multinationals Help or Hurt Emerging Economies?" presents the main findings of Diana Van Patten and Esteban Méndez-Chacón's 2020 working paper. “Multinationals, Monopsony and Local Development: Evidence from the United Fruit Company.”

Her career path has placed her well to research such question. She worked as an undergraduate student researcher at the Central Bank of Costa Rica, then she went on to the PhD program at UCLA, where she continued to study the economy of her home country. Her current research utilizes large data sets to answer a range of questions about the long-term effects of the presence of foreign firms – from quality of life for Costa Rican citizens, to environmental impacts, to political attitudes towards foreign trade.

Discovering a positive impact

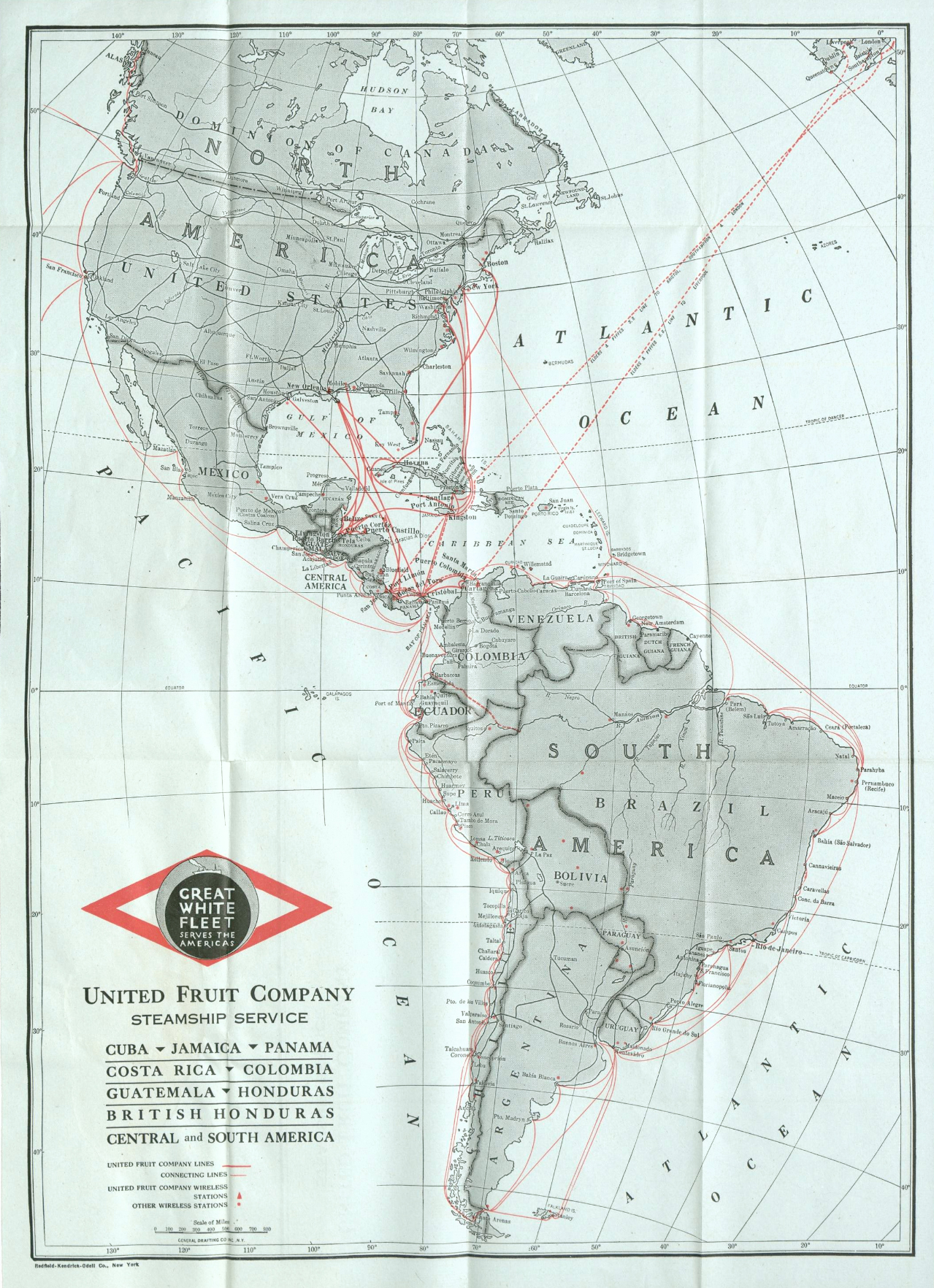

The UFC’s history as the largest agricultural monopoly in recent history began in Costa Rica. In 1899, the company was granted a concession of land to complete a railroad across the country, and shortly after the completion it began to experiment with banana cultivation and export. The initial plantation was a financial success, and the company went on to establish more plantations in other Central and South American countries. By the 1950s, UFC bananas comprised 58% of Costa Rican exports.

As it developed, the UFC gained an international reputation for exploiting workers, bribing government officials, and ruthlessly consolidating monopolies. In nations including Guatemala and Honduras, relationships between the firm and government officials and discouragement of transportation development led to corrupt political leadership and massive class stratification. The connections between the UFC, widespread poverty, and political instability in these countries have been immortalized in works by poet Pablo Neruda and novelist Gabriel García Márquez, among other socially conscious writers. But the comparatively positive impact of the firm in Costa Rica – and the reasons for this difference – have received considerably less political and scholarly attention.

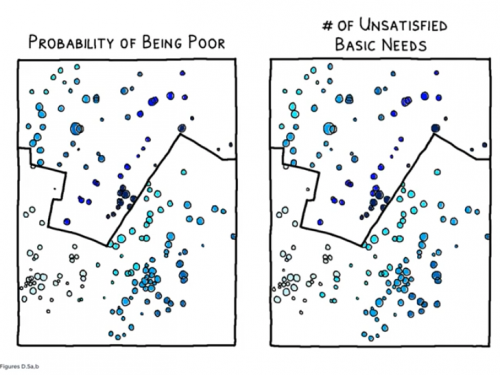

To assess the impact of the UFC on Costa Rican living standards, Van Patten and co-author Esteban Méndez-Chacón accessed census data between the years 1973 and 2011. Data from the late twentieth century in a randomly assigned portion of UFC properties showed sharp distinctions in the living standards of residents, aligning directly to the contours of the boundary of lands UFC obtained by concession. Households within the concession showed a 12.4% lower probability of being poor (26% relative to the sample mean). The probability of being poor or having low-quality housing was still lower for these households in 2011, decades after the UFC left the concession.

This was contrary to Van Patten’s expectations, given the record of monopolization and dangerous labor practices that the firm garnered throughout Central and South America. But, looking closely at detailed census records and company reports, she and her coauthor were able to uncover complex dynamics at play between the United Fruit Company and the Costa Rican labor market.

Meet the new EGC Affiliates, Fall 2021

With the launch of the Fall 2021 semester, EGC is welcoming new affiliates and visitors – part of a long history of supporting development economics research through collaboration.

The key finding of Van Patten’s paper is that worker mobility – meaning their ability to relocate for employment – supported company investment in the local economy and prevented some of the exploitation seen in other nations. Agricultural workers in Costa Rica often worked in short-term bursts, moving between coffee and banana plantations according to season, so the UFC had trouble attracting a long-term workforce. Workers were accustomed to traveling in and out of cities for work, leaving their families for only short periods of time. In order to establish the firm as a long-term employment opportunity, the UFC built schools, hospitals, and free housing for their workers.

A structural model used in the paper asked: what would have happened in Costa Rica if worker mobility would have been lower? “[In the] counterfactual, we find that if worker mobility would have been half the amount of what we estimate, the company would have had a negative and persistent effect on living standards,” Van Patten said. “Worker’s outside options and mobility are key.”

In Guatemala, for example, evidence suggests that worker mobility was lower. “There are letters from [United Fruit] Company officials to government officials disincentivizing the construction of roads. In these places, when we do a much more naive comparison between UFC and non UFC areas, we find that UFC areas are worse off today.” Worker mobility was a key incentive for the company to invest in the local economy, leading to the long-term positive effects seen in Costa Rican citizens.

Other Impacts of Foreign Firms in Costa Rica

In her new appointment at SOM and EGC, Van Patten is building on her study of the UFC to focus on other impacts of the presence of foreign firms in Costa Rica.

In an upcoming project in the same body of work, she uses agricultural census data to examine the long-term environmental effects of the presence of foreign agricultural firms in Costa Rica. Census data establishes the productivity of individual plots of land, owned by foreign and local firms, between 1964 and 2014. Using a similar methodology as in the UFC paper, she compares foreign and domestic-operated plots side-by-side along vectors of productivity and pesticide or chemical use.

Van Patten explained her findings so far: “If the plot has been exploited or used by a foreign producer, it's true that the plot is more productive, [but] contemporaneously, it also uses more chemicals and fertilizers. Over time, the productivity of that plot decreases significantly.” She explained that exposure to foreign firms leads to negative long-run effects on productivity. “In particular, we see that heavy use of chemicals and fertilizers is associated with health problems in the population. So there are not only good aspects, but also bad ones of hosting these firms.” This finding reflects the complicated history of foreign firms in Costa Rica, yielding financial profits, employment, and investment but also long-term environmental costs.

Another upcoming paper uses unique voting data to gain insights into how Costa Ricans feel about the complex history of foreign firms in their country. Questions about citizens’ political views and voting behavior are hard researchers to answer empirically, as people often misrepresent their vote in surveys, giving the answer they think the surveyor wants to hear. However, a quirk in how Costa Rica conducts its elections gives Van Patten a better lens on voting behavior. In 2007, Costa Rica held a nationwide referendum that allowed voters to decide whether to uphold the DR-CAFTA (a NAFTA-like trade agreement between a group of several Central American states and the United States). While the US has been Costa Rica’s trading partner for many years, the vote was extremely close, passing by a margin of about 51%, with almost 60% of the country’s citizens participating in the referendum.

Costa Rica organized the election by having people vote in groups separated alphabetically by last name in public-school classrooms. This rendered voting data identifiable at the group level of 500 voters. Linking voting data with employer/employee data, Van Patten is able to ask: are people whose employers benefit from foreign trade more likely to vote?

“We find that that’s the case”, she said.

Additionally, Van Patten finds that the firm at which a person is employed is significantly more likely to impact participation in the vote than the type of labor they do or the industry they are in. Across skill levels and industries, people employed by firms that could benefit from foreign trade were more likely to vote in favor of the free trade agreement.

At Yale and the EGC, Van Patten will continue to pursue a broad range of research topics pertaining to the presence of foreign firms in developing countries. She will pass on a sense of both inquisitivity and responsibility to her students at the School of Management. Development economics research, she said, “can be a very powerful tool. You feel like your work can make a difference in the well-being and life quality of people in the developing world.”

Clare Kemmerer is a second-year graduate student in the MAR program at the Yale Institute of Sacred Music, concentrating in the study of visual arts and material culture, and an EGC Communications Intern. Photos by Vestal McIntyre for EGC.