By Rohini Pande and Charity Troyer Moore

This article first appeared in the New York Times on August 23, 2015.

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Usually, economic growth in lower-middle-income countries creates more jobs for women. But as India’s economy grew at an average of 7 percent between 2004 and 2011, its female labor force participation fell by seven percentage points, to 24 percent from 31 percent. Despite rapidly increasing educational attainment for girls and declining fertility, the International Labor Organization in 2013 ranked India 11th from the bottom in the world in female labor-force participation.

Research shows why this matters: Working, and the control of assets it allows, lowers rates of domestic violence and increases women’s decision-making in the household. And an economy where all the most able citizens can enter the labor force is more efficient and grows faster.

For India’s government to maintain the country’s progress into the ranks of middle-income countries, it needs to understand why female labor force participation is falling, and develop an effective policy response.

Data shows a complex and puzzling picture: Women are becoming more educated but, simultaneously, the positive labor market effects typically associated with higher education are declining.

It’s not that women don’t want to work. Our analysis of data from India’s latest labor survey shows that over a third of women engaged primarily in housework say they would like a job, with that number rising to close to half among the most educated women in rural India.

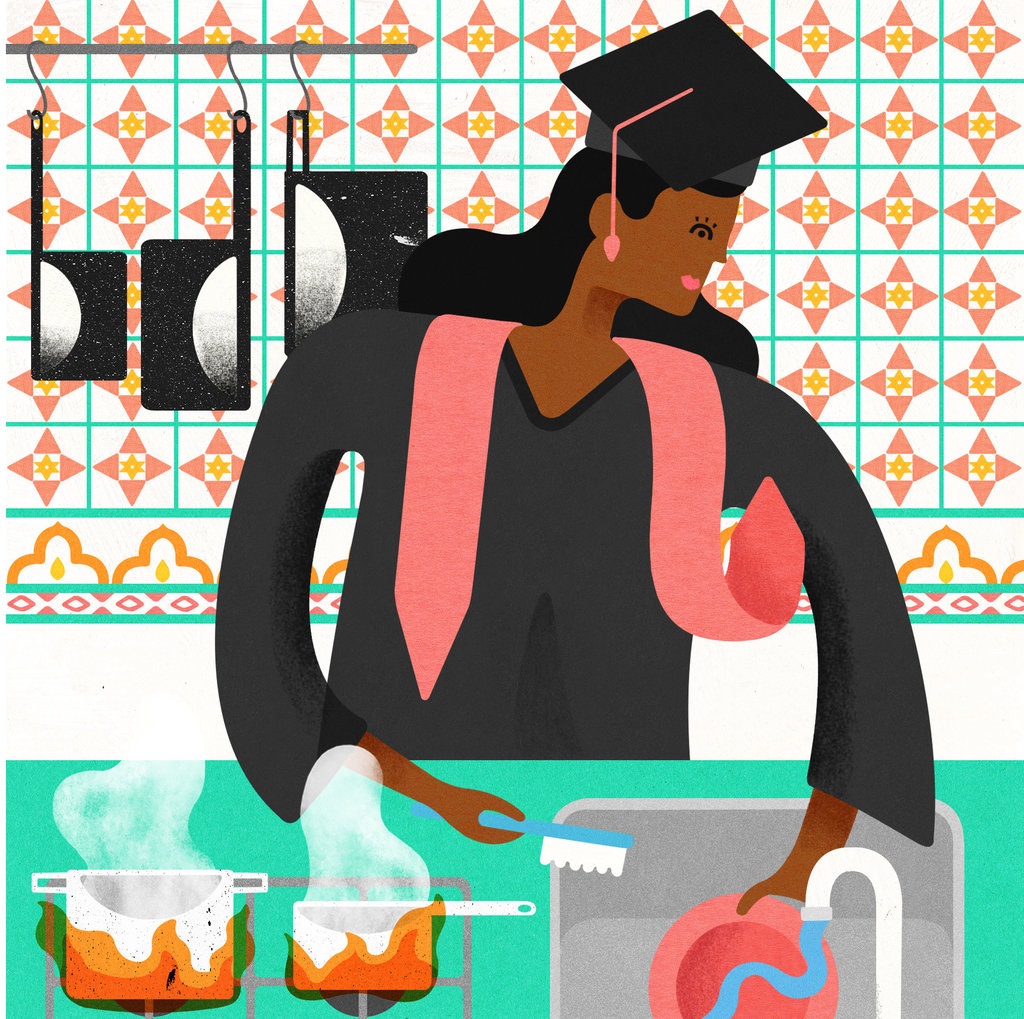

Much of the reason they don’t work appears to lie in the persistence of India’s traditional gender norms, which seek to ensure “purity” of women by protecting them from men other than their husbands and restrict mobility outside their homes.

Home-based wage work or entrepreneurship, even when it exists, rarely transforms and liberates the worker. In our work with young women targeted by vocational training programs in rural India, we have witnessed men refusing to allow their daughters, wives and daughters-in-law to leave the village for training and subsequent job placements. Trainers, whose pay depends on employment outcomes of their trainees, are reluctant to work with women who may be more likely to refuse job placements. In urban India, the jobs are geographically closer but women struggle with lack of access to traditional male-dominated job networks.

So, women often end up in lower-paid and less-responsible positions than their abilities would otherwise allow them – which, in turn, makes it less likely that they will choose to work at all, especially as household incomes rise and they don’t absolutely have to work to survive.

This picture may seem daunting. Yet seemingly immutable norms can crumble when labor markets begin to properly value women’s work. The garment industry in neighboring Bangladesh accounts for over 75 percent of national export earnings and, strikingly, nearly 80 percent of Bangladesh’s four million garment-sector workers are women. The explosive growth of that industry during the last 30 years caused a surge in large-scale female labor force participation. It also delayed marriage age and caused parents to invest more in their daughters’ education. Those changes, in turn, very likely reinforced Bangladesh’s strong growth record in the garment sector.

In India, in professional sectors where there has been sharp expansion, and where working conditions are clearly good, women have done very well. One example is financial services: While only one in 10 Indian companies are led by women, more than half of them are in the financial sector. Today, women head both the top public and private banks in India.

Another example is India’s aviation sector, which positioned itself early on as a female-friendly profession. Today, 11.7 percent of India’s 5,100 pilots are women, versus 3 percent worldwide.

These successes, though, represent a few thousand women in a country of hundreds of millions. India needs policies that will create a rapid and widespread demand for women’s work similar to what happened in Bangladesh. In the absence of a fast-growing manufacturing sector that creates jobs for women, the answer for India may be expanding gender quotas in the labor market.

India has already successfully used such quotas in local elections. Research shows that in places with quotas, more women ran for office and more women won, even after the quotas were no longer in place. The quotas raised parents’ aspirations for their daughters, and the girls’ aspirations for themselves. The increase in female elected leaders also resulted in better outcomes for women overall: More funds were spent on public goods and services that benefit women, and women were more likely to speak out about acts of violence. The economy benefited too, as, more women took out business loans in villages that had a quota.

India’s other big experiment in gender quotas, starting in the 1980s, was with female teachers in schools. Again, using data from India’s labor surveys, we find that education is the largest sector employing women in urban areas and the largest, except for agriculture, in rural areas. Introducing, and rigorously evaluating, quotas in other sectors that are accessible to young educated women and that offer them an attractive career in a safe workplace is a promising next step.

Moreover, to ensure that the supply of able and trained women meets the new demand, the establishment of quotas needs to be supported by safe and effective job training and placement programs.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Independence Day speech last year emphasized the need to transform India’s gender norms. Little, though, has changed in the year since.

What is needed is obvious: Mr. Modi and his advisers should make wider use of the policy tools already available, including quotas and training, to ensure that all of India’s women have the opportunity to undertake rewarding work — work that will allow them to determine the course of their own lives, those of their families and that of their country.