One reason for low demand for skilling in India quickly became apparent when EPoD researchers compiled evidence from the National Sample Survey. Government-funded skills training programs typically required entrants to have a 12th grade education. But in rural areas only 14 per cent of males and 10 per cent of females in the targeted age range (18 to 35) had reached that level of education. A larger group, 18 per cent of males and 12 per cent of females, had ended their education at 8th or 10th grade.

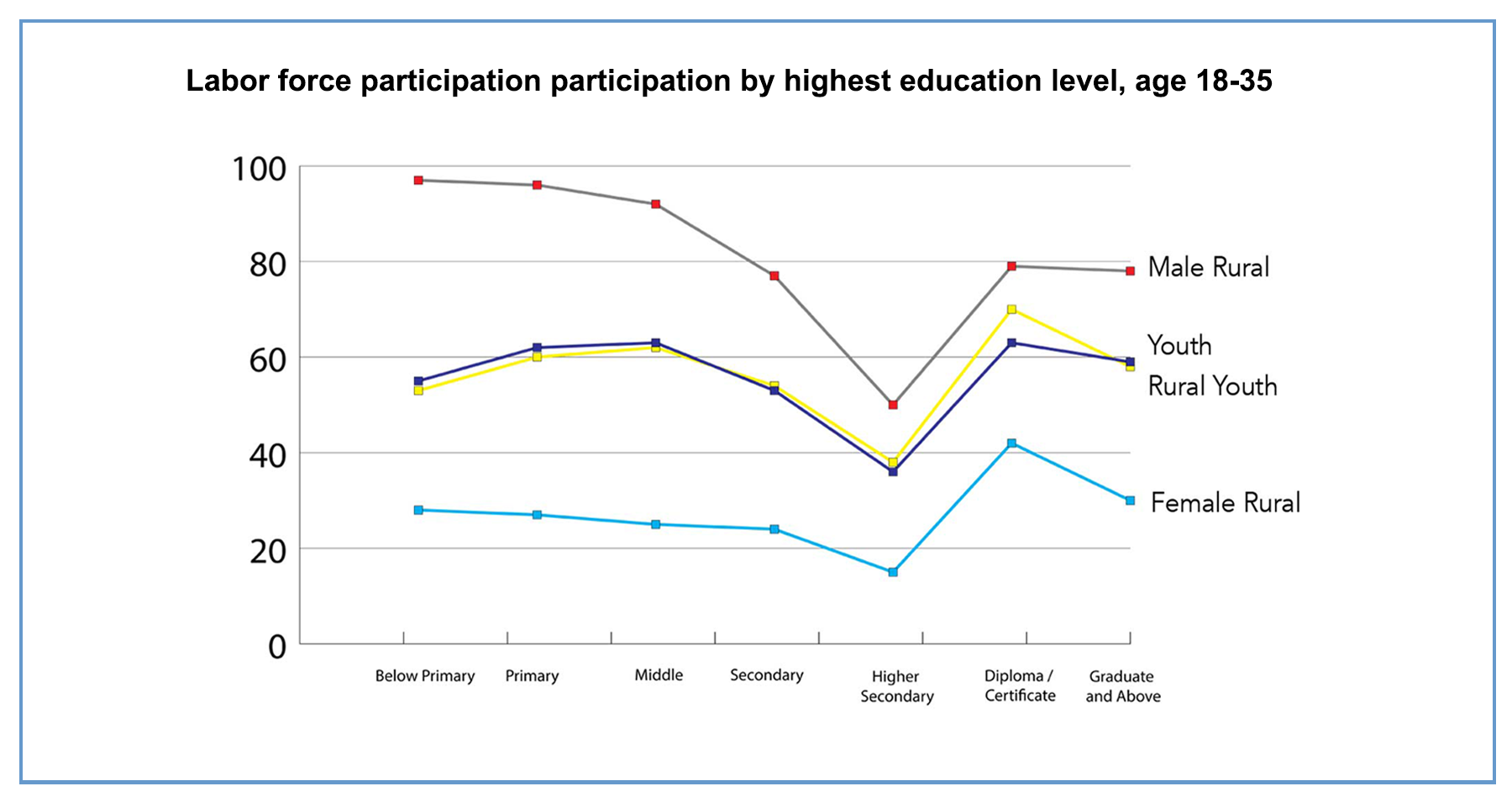

You can see in the graph below that there is a dip in the relationship between education and labor force participation among rural youth. This is consistent across genders and geographical regions. Those who completed 11th or 12th grade were less likely to participate in the labor force than those less educated. So youths who only just completed high school or dropped out just before graduating were trapped in a kind of limbo – less likely to take low-paying, unskilled jobs than those of lower education, but shut out of jobs that required a specialized education.

This combination of facts – all available in existing government data – suggested that a longstanding requirement had created a mismatch between the supply of training and the group that would best benefit from it. Only a few training programs (e.g. hospitality) were open to those who had completed 8th or 9th grade, and the programs that led to most lucrative jobs (e.g. IT) mostly targeted those with some college education. Opening up more training to the groups at the bottom of the dip promised to include a huge number of underemployed rural youth. EPoD’s Charity Moore and Soledad Artiz made the case for casting a wider net in an op-ed first published on IndiaSpend, a data journalism website.