The pioneering career and indomitable spirit of economist Cynthia Taft Morris

By Lisa Qian

September 21, 2020

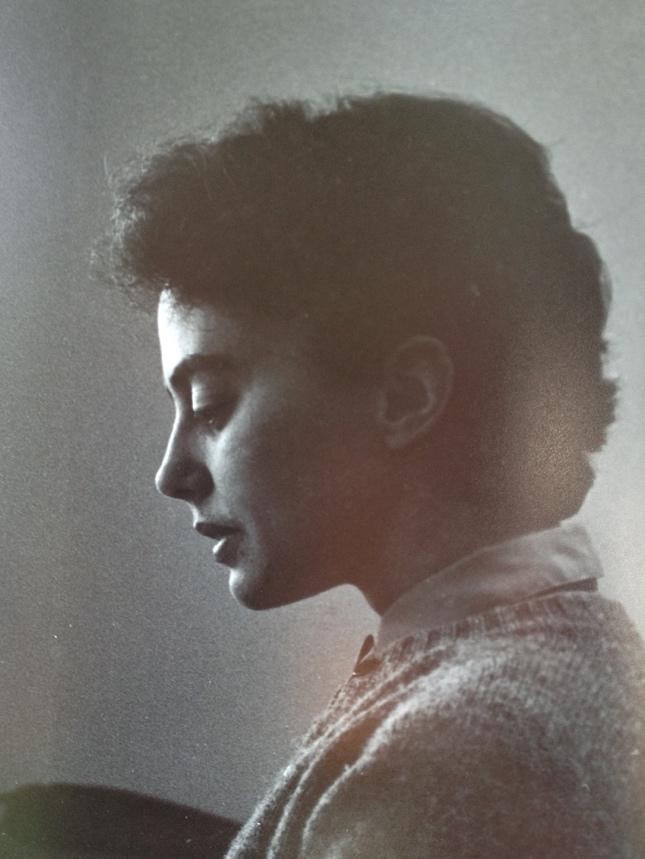

Throughout Cynthia Taft Morris’s life, she was known for her fierce resilience, determination, and independence.

In an era when few women pursued academia, Taft Morris earned a Ph.D. from Yale in economics and lobbied her way into becoming one of the first women on the economics faculty at both American University in Beirut and American University in Washington DC. In addition, her collaboration with fellow pioneering scholar Irma Adelman yielded pioneering insights into the importance of social and political factors when considering economic development.

Taft Morris never let her status as a person with a disability define her options. “My mother didn’t bristle at discrimination,” her son David Taft Morris said. “She ignored it. She essentially forced her own accommodations on whoever she was interacting with.”

Early Life

Cynthia Taft Morris was born Cynthia Herron Taft in 1928, one of seven children in a distinguished family. Her grandfather was President William Howard Taft, and her uncle was Robert A. Taft, who served as a senator in the 1940s and 1950s, briefly as Majority Leader.

When Taft Morris was 13 years old, a polio infection paralyzed her from the waist down. She refused to use a wheelchair, and instead went through intensive physical therapy to learn to walk with crutches. This experience “developed her strength of will, which served her well through the rest of her life,” according to David Taft Morris.

Though her family legacy was rooted in the Republican party, she formed a liberal political viewpoint early, under the influence of her mother, whose own views were socialist. Taft Morris’s mother was also influential in her post-polio recovery, taking her to the Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation in Georgia, a polio rehabilitation facility founded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Taft Morris attended Vassar College, where she became interested in economics and, specifically, in economic history. Upon receiving her undergraduate degree in 1949, a desire for adventure took her to Europe in the aftermath of World War II. She studied at the London School of Economics (LSE); after receiving her master’s degree, she worked for the Mutual Security Agency, a Paris-based organization founded by the US to continue the economic recovery work of the Marshall Plan.

Time at Yale

At this point, Lloyd Reynolds, the chair of the Yale Economics Department, was looking for a research assistant who had a background in labor economics and could speak French and German. He reached out to Taft Morris’s LSE tutor, who recommended her. In New Haven, her position transformed into a spot in Yale’s Ph.D. program, where she was one of the few woman students.

Though Reynolds made her a co-author of his book, departmental policy disallowed her from serving as a teaching assistant. Knowing that she would be moving to Cambridge, MA, where her fiancé Donald Morris was to begin a Ph.D., her sights shifted to Harvard University. By her own admission, “with two glasses of sherry under [her] belt,” she called up the chair of the Harvard Economics Department and persuaded him to allow her to be a teaching fellow. She was also one of the first woman tutors at one of Harvard’s houses.

After graduating from Yale

After Taft Morris received her Ph.D. from Yale in 1959, she followed her husband overseas on Foreign Service postings, first to Geneva, Switzerland, and then to Beirut, Lebanon. Determined to find a teaching position at the American University of Beirut, she convinced the Economics Department to hire her as a visiting assistant professor, the first woman professor.

At a time when wives of Foreign Service Officers were expected to host and entertain guests of their husbands, Taft Morris refused to ask permission to work; instead, she went to the Deputy Ambassador’s office to declare her plans to him. There was nothing he could do to stop her.

“Cynthia just wouldn’t let anything stop her from what she wanted to do. And always with a laugh or a smile.” – Ivy Broder, former dean of academic affairs and interim provost at American University

“Men had amazing ways of blocking women from good jobs,” Taft Morris would later write. “When we met with the kind of stupidities I have recounted [such as being blocked from teaching positions], we thought: ‘What a stupid man. I'll go find an intelligent man to help me out.’ If we were determined enough, we found one and kept going.”

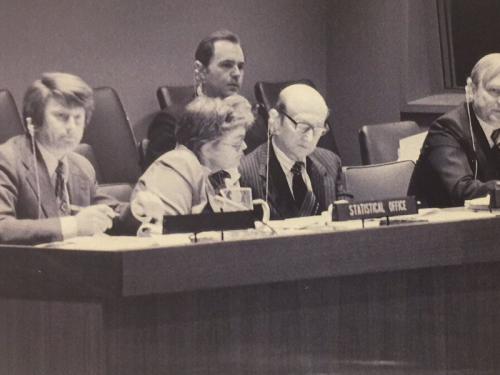

She returned to Washington, DC in 1962. There, she met Irma Adelman while working at the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), with whom she enjoyed a fruitful collaboration that lasted many years. To Adelman’s work in development, Taft Morris brought an economic historian’s perspective; she was one of the first scholars to incorporate the study of economic history into development theory. Together, Taft Morris and Adelman argued for the interdependence of development policy and social and political institutions. Their work was firmly rooted in practical considerations at a time when the study of development often focused on abstract mathematical models, and many of their pioneering insights are now widely accepted within the field.

“Cynthia and Irma are female giants and pioneers of development economics,” said Maria Floro, a professor at American University and friend of Taft Morris. “They certainly deserve to belong among the ranks of influential development economists who are men.”

Later in her career

To receive National Science Foundation funding for her work with Adelman, Taft Morris needed an academic appointment, so she persuaded American University to give her a role on paper. Her time at American University, however, turned out to be far more than symbolic – she became a mainstay in the Economics Department and served as a respected mentor to other women professors. She also negotiated a number of accommodations necessary for persons with disabilities: a dedicated parking spot (before disability parking was mandated by the Americans With Disabilities Act), as well as a ground-floor office near the Economics Department building entrance.

Ivy Broder, who recently retired from a 40-year career at American University and served as dean of academic affairs and interim provost, did not have a single woman mentor in her study of economics before Taft Morris. “It was amazing to me that here was a female professor who welcomed me,” Broder said. “Cynthia helped me become a stronger person and develop more confidence in myself.”

After 19 years at American University, Taft Morris moved to Smith College, where then-President Jill Kerr Conway was looking to hire senior woman professors to mentor young female faculty. The economics department there hadn’t had a tenured woman professor in decades, and she was a natural choice. Taft Morris pursued her academic career while remaining dedicated to raising a family – an achievement she valued greatly, according to her daughter, Michele Taft Morris.

After retiring from Smith, she moved back to Washington, DC, where she was an economist-in-residence at American University. At this time she used a wheelchair to get from home to campus –with a sign attached to the back that read, “Don’t push me, I’m working out.” Even when working from bed some years later, she learned to use voice-activated software so that she could continue to write and had students deliver papers to her.

She died in 2013.

“Cynthia just wouldn’t let anything stop her from what she wanted to do,” Broder said. “And always with a laugh or a smile.”

Lisa Qian is a 2020 economics graduate of Yale College, and a former intern at the Economic Growth Center.

As Yale celebrates the 50th anniversary of coeducation and the 150th anniversary of women students at the university, the university’s pioneering woman scholars are also receiving renewed attention. In addition, the Economic Growth Center celebrates its 60th anniversary in 2021 and wishes to honor the women who paved the way for successive generations. This article is one is a series to recognize women who have been a part of EGC and Yale Economics. The other articles can be found here.