Q&A: Naomi Lamoreaux and Stephen Haber on how patent systems have enabled innovation and growth

The Battle Over Patents: Naomi Lamoreaux and Stephen Haber on the formation and fights of the US patent system

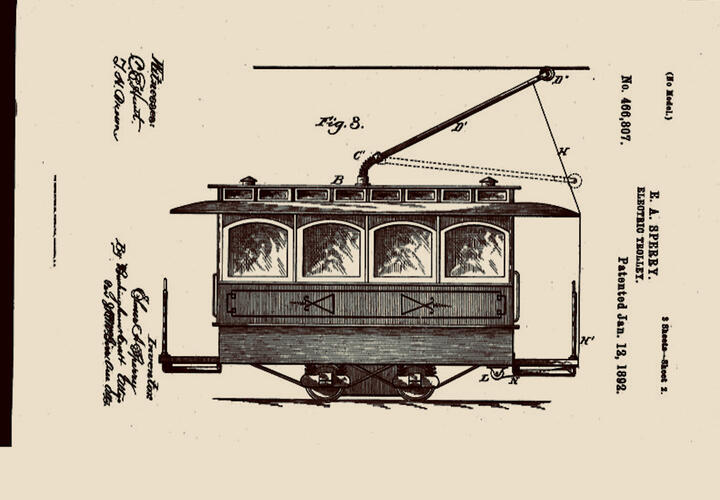

The US patent system emerged in the 19th century, offering inventors greater control over their ideas, protecting and encouraging innovation. In the time since, similar systems have been adopted around the world, guiding the ways that new technologies are created, shared, and used. Yet the very aspects of patent law that contributed to rapid economic growth and technological innovation – the ability it grants inventors to sell or license the rights to patents and collect royalties from those using patented products – are now challenged by large firms, who accuse smaller firms or individual inventors of “monopolization” of the component technologies they have patented.

Naomi Lamoreaux (left), Stephen Haber (right)

The history, strengths, and weaknesses of the patent system – and the profit-driven controversies that threaten it – are the subject of a new volume of essays, The Battle Over Patents: The History and Politics of Innovation (Oxford University Press, 2021). The editors of the volume, Naomi Lamoreaux, the Stanley B. Resor Professor of Economics and History at Yale and an affiliate of the Economic Growth Center, and Stephen Haber of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University discussed patents and growth in an EGC interview.

In your introduction, you write that this book largely answers the question: what problem do patents solve? What is that problem?

Haber: For most of human history, the big problem was that people who invested in coming up with a better way of doing things couldn’t reap the returns on that investment unless they could keep it a secret or unless they could protect it by being a member of a guild. And so technological progress tended to be slow because of what economists call the free rider problem. You invest all this time and energy at getting good at something or inventing a way of doing something, and then someone else just can come along and copy you.

What the patent system did was break the free rider problem because it allowed an inventor to have a property right to the idea. Then if somebody copied that idea, tried to free ride, it allowed the inventor either to stop them or, more typically, to get a royalty from them from using the process. That was allowed once the patent system matured by the 18th century in Britain and then in the 19th century in the United States. Once that happened, it allowed a market to develop in inventive activity. Ever since, there has been an active market of new ideas, new processes, and new ways of doing things. Specialized firms develop patented ideas that they sell on to a market.

Lamoreaux: Without the patent system we would be in a world where it would be very hard to develop complicated processes that require multiple inputs from different firms. With it, we have intellectual property rights that allow people to be secure in the knowledge that their ideas will not be stolen by the parties they're collaborating with.

EGC Affiliate Spotlight: Naomi Lamoreaux

What can late 19th and early 20th century antitrust efforts against Standard Oil and US Steel teach us about how Google, Amazon, and other tech giants should be regulated today? Lamoreaux uses historical analysis to inform modern thinking on monopoly power.

Your new book draws on examples from the history of the patent in the United States to analyze our modern patent system. Why do you think understanding the historical context of this system is important?

Lamoreaux: A good example is litigation. There are a number of books and articles that look at what is called the litigation explosion in patents. And now people say, “Oh, this is a terrible system, it leads to a large profusion of lawsuits.” One question you immediately want to answer then is: is there actually a lot of litigation? How does this compare with the amount of litigation historically?

One of the contributors to the book, Chris Beauchamp, has done this fantastic study where he went back to the 19th century and looked at two federal courts out of all the federal district courts in the country. He found that just in those two courts in the 19th century, there was as much litigation or more litigation as in the whole country today relative to the number of patents that are in force. That's a striking finding, because the country didn't fall apart. Technological change didn't stop. In fact, the period when there was all this litigation was also a period of tremendous economic growth and development. That suggests that people who are hysterical about litigation right now are overreacting, and that there are some very simple solutions that would reduce the amount of litigation without damaging the operation of the patent system.

The book suggests that patents can help “technologically laggard” countries “catch up” with the more developed nations. How does this happen?

Haber: The United States itself was once such a country, which caught up with its European competitors, but if you look at other countries around the world that were poor in the 20th century and then caught up, there's two that jump out at me: South Korea and Taiwan.

Circa 1950, both Taiwan and Korea were very poor countries. They caught up by building technology-based industries. Among the things that facilitated this transition were intellectual property rights that allowed their firms to absorb technologies from other countries and to collaborate with firms in the United States.

Program in Economic History

The field of Economic History uses empirical evidence, the tools of economics and econometrics, and appreciation of institutional context to understand how economies functioned in different times and places, and how present-day economic problems reflect earlier development.

Without a patent system that would protect property rights, an American or German or British firm won't go into a developing country and create a manufacturing facility and partner with local entrepreneurs because they worry, quite rightly, that they'll get hit by the free rider problem. But when a country has a patent system, it gives the foreign firms that are transferring technological knowledge assurance that they will not be subject to free riding. And it allows, therefore, for technology transfer and the building of domestic capability technological capabilities.

How have US-style patent systems changed as they have been adopted internationally? Why were they appealing?

Lamoreaux: When countries are adopting patent systems, they are to a large extent modeling them on the system that emerged in the US. And the single most important aspect that they're copying is the idea that patents should be examined by professional examiners for the patentable criteria – utility, for example--and to make sure that they're not just copies of technologies that are already in place.

One other feature of the US patent system that's very important is that patents were very cheap, and that puts the cost of a patent within reach of ordinary people. You have to hire a lawyer to help you get your patent through the bureaucracy, but it's still cheap. And many patent attorneys would take shares in the patents as payment as a way of helping inventors who had really great technological ideas to get started. The system was geared to small investors and allowing them to participate in technological progress.

The design of any patent system is structured by the interests of the people who are pushing for it. Our system was created when there weren't large firms, but other systems were created when large firms could lobby for provisions of the patent system that were favorable to them. When countries imitated the US examination system, they often did not imitate the cheapness of the system. The US patent system only awarded patents historically to the first and true inventor, but when Germany and other countries adopted their patent systems, they awarded patents to the first to file, a standard that advantages large firms. Independent inventors have a more difficult time with that standard.

What is the battle that is referred to in the title “The Battle Over Patents?” While editing and compiling the essays for this book, what did you learn about patents that surprised you?

Haber: One concept that crystallized for me was that there is now an assault on the patent system. It's neither a Democrat nor a Republican issue, and it's been going on since around the year 2000. The claim is that patents are impeding technological progress.

In any product, there is an amount of economic surplus that can be generated that is bounded by the demand for the product. Take laptops: firms at the end of the production chain are earning the revenues from consumers and they have to share them with everybody up the production chain, from the firms that make the glass for the laptop to those that make the keyboards to those that create the technologies that allow us to communicate with each other.

Firms up and down the production chain will use every arrow in their quiver to fight over that economic surplus. That battle is never-ending in the system – and that is by design. There is no frictionless world when money is at stake. The battle will be fought in the courts, in terms of legislation, antitrust policy – it will even be fought in academia. Indeed, law reviews are full of articles about how patents impede technological progress.

What needs to be understood is that the current battle over patents is really an inter-industry fight. Big-tech firms at the end of the production chain are fighting with smaller firms further up the production chain over the apportionment of the economic surplus generated by the production chain. Basically stated, the big-tech firms are squeezing their suppliers. The claims that are currently made about patents getting in the way of innovation need to be understood in terms of this endless battle within industries.

Lamoreaux: History gives you some perspective on current problems. It shows that, actually, the debate over patents is to a large extent by interested parties. They're fighting over profits, the surplus from innovation, and that is to be expected because there's money at stake – real money.

Written by Clare Kemmerer