Professor Naomi Lamoreaux on antitrust regulation, and how economic history speaks to development

What can late 19th and early 20th century antitrust efforts against Standard Oil and US Steel teach us about how Google, Amazon, and other tech giants should be regulated today?

A lot, according to economic historian Naomi Lamoreaux, the Stanley B. Resor Professor of Economics and History. In her view, economic history is integral to the study and analysis of business, economics, and economic development.

“Economic historians look at how economies developed in the past, but not just for antiquarian reasons,” she said. “Some of those lessons are relevant to development in the present. That’s really what economic historians care about.”

Initially interested in math, Lamoreaux was drawn to economic history as a graduate student because of how it applied quantitative thinking to real-world issues. “At the time, a new style of economic history was blossoming that brought economic theory and econometric techniques to bear on historical problems,” she explained. “I found that very exciting.”

Learn about the Program in Economic History

The Program exists within the Economic Growth Center to foster research of the long-term development of economies. Visit the Program's website for information on weekly events, mini-conferences, and other program activities.

Lamoreaux became interested in late 19th-century monopolies while completing her PhD at Johns Hopkins University. Her dissertation culminated in her first book, The Great Merger Movement in American Business: 1895–1904. She has since become a leading expert on a broad range of topics in US business and economic history, from finance to intellectual property rights and corporate governance. More recently she returned to her roots in US antitrust history.

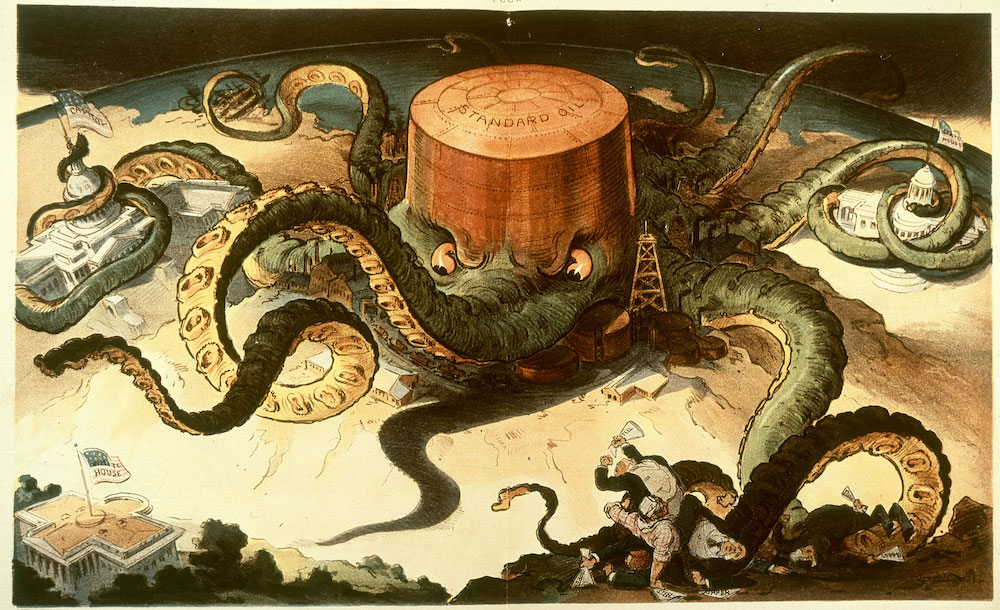

In a 2019 paper titled “The Problem of Bigness: from Standard Oil to Google,'' Lamoreaux described how US policy makers have struggled to deal with monopoly power for more than a century. As early as the 1880s, concerns emerged over how dominant companies like Standard Oil used their size to create barriers of entry for new firms.

Photo by achinthamb, Shutterstock

Photo by achinthamb, Shutterstock

Google Headquarters in Mountain View

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

A 1904 political cartoon showing a Standard Oil tank as an octopus with many tentacles wrapped around the steel, copper, and shipping industries, as well as a state house, the U.S. Capitol, and one tentacle reaching for the White House

“Even efficient firms doing wonderful things want to prevent competitors from entering markets,” she observes. “We should worry whether today’s big tech companies are not just innovative and exciting, but are also keeping out new players who could push the innovation frontier even further.

Since regulation could help more new firms and ideas enter the market, Lamoreaux thinks the current scrutiny facing tech giants is potentially good for long-run economic growth. But her study of economic history reminds her that finding the right balance can be difficult.

“Policy can go too far,” she says. “Sometimes regulation is too lax, and sometimes it’s overly burdensome. Throughout history, one extreme tends to lead to the other.”

Written by Sarah Guan