Did women have an impact on social mobility in pre-modern economies?

EGC Research Summary, April 2023

Historical studies of social mobility typically overlook the role of women: it is generally assumed that before the industrial age, women lacked much ability to change their social status except through marriage or kinship with men. EGC affiliate José-Antonio Espín-Sánchez and co-authors analyzed data comprising all 18th century marriage records from Murcia, an ancient region on Spain’s southeastern coast, to generate surprising insights on women’s ability to influence the social status of their children – particularly their daughters.

In pre-modern Spain, social mobility can be traced inter-generationally through the honorific titles don and doña, which denoted high-class status.

Don and doña were not strictly transferred through inheritance or marriage and could be gained regardless of gender; from a data set containing more than 18,000 marriages, the researchers documented 1,416 doñas and 1,160 dons.

Doña mothers influenced their children’s status as much as don fathers did, though the strength of the influence varied by gender: the daughter of a doña was about twice as likely as her son to achieve high status, with similarly gendered correlations for the children of don fathers.

In mixed-status marriages, by contrast, the high-status parent had a stronger influence on the status of their children’s spouses of the opposite gender, likely due to the gendered social dynamics of match-making.

Tracing social mobility through 300-year-old marriage records

Very little is known empirically about inequality and social mobility in pre-modern economies, given the scarcity of economic data. What data do exist typically overlook women, who often appear in the written record only in reference to their husbands and fathers. This contributes to a general misconception that women’s social status has historically always been dependent on men.

This was not always the case, according to research published in a recent issue of The Journal of Economic History by Espín-Sánchez and his co-authors Salvador Gil-Guirado, from the University of Murcia, and Chris Vickers, from Auburn University. The researchers focused on a unique measure of social status used in pre-modern Spain: the honorific titles of don and doña, which denoted high (but not noble) status in recognition of one’s economic, social, or cultural standing. Once gained, an individual could not lose the title, but its passage from parents to children was not guaranteed: dons and doñas occasionally had children who did not receive the title, and vice versa.

This paper is extremely innovative in measuring inter generational mobility for women," – Dan Bogart, Co-Editor of the Journal of Economic History

Importantly, the titles were also not driven by gender. Doña measured the status of women directly – it was not simply transferred through inheritance or marriage, and marriages of mixed status occasionally occurred. (For more information on Spanish honorifics, see Perez Leon (2012) and Pita Pico (2013).)

Given these factors, don and doña are reliable measures for tracing social mobility in pre-modern Spain – and for understanding complex gender dynamics in that society. “In our case, it is useful because the title was objectively – or at least consistently – certified by the local priest,” said Espín-Sánchez, who grew up in southern Spain. “Of course, some people would call themselves by the title, including on documents like the census, but the priest will not record them as such.”

To conduct their analysis, Espín-Sánchez and his co-authors accessed 18th century marriage records from church archives in Murcia, a centuries-old bureaucratic capital with exceptionally well-preserved historical documents, and digitized a large number of paper records. In fact, the researchers found some evidence of fully upwardly mobile women in 18th century Murcia: 84 brides (out of more than 18,000 marriages in their data set) recorded as doñas despite both of their parents and the groom lacking equivalent status.

"This paper is extremely innovative in measuring inter generational mobility for women," said Dan Bogart, Professor of Economics and the University of California, Irvine, and Co-Editor of the Journal of Economic History, where the paper was the lead article of its issue. "It gives evidence for a gendered transmission of status in Spain. In other words, mothers' status matters more for their daughters and fathers status matters more for their sons. These findings, with wide implications, are the result of careful research into historical marriage records. It should inspire more research on gender and mobility in other contexts."

Fabio Alessandro Locati, Wikimedia Commons.

Fabio Alessandro Locati, Wikimedia Commons.

The cathedral in Murcia, where many records are stored.

Doña power: women’s surprising influence over their children’s social mobility

The team began by observing the recorded title of every bride, groom, and both sets of parents at the time of marriage. If that couple had children who subsequently married, the researchers recorded the same six data points (bride, groom, and both sets of parents) at the time of the next marriage, then linked the records. In this way, with just two marriage documents, it was possible to observe social mobility across multiple generations – and to assess the specific role that gender played.

They found substantial differences across gender in how status was transmitted. While the status of both parents affected their children’s status, the strength of the influence varied significantly by gender. The daughter of a doña was more likely to achieve high status than a doña’s son, with similarly gendered correlations for the children of don fathers. In general, parents influenced the social status of their same-gendered children about twice as strongly as their children of the opposite gender (correlation coefficients of 0.6 and 0.3, respectively).

Contrary to the conventional wisdom, these results underscore that mothers played an important role in their children’s social mobility in pre-modern Spain – for their sons but especially their daughters. In addition to providing an honorific (or lack thereof) to their daughters, the researchers suggest that women imparted a number of less tangible influences that contributed to women’s mobility – for instance, passing on gender-specific social and economic knowledge and skills to help their daughters find a good marital match.

Assortative mating: similar findings with opposite gender dynamics

The researchers found that doña mothers had little influence on whether their daughters married a don – and don fathers had little influence on whether their son would marry doñas. By contrast, they found that having a doña mother increased her son’s likelihood of marrying a doña. Likewise, having a don father increased his daughter’s likelihood of marrying a don.

Espín-Sánchez and his co-authors interpret these findings to mean, only one parent had access to higher-status social networks to find a good match for their child. If a don husband was the high-status parent, he could access high-class don circles to find an advantageous match for his daughter; if a doña wife was the high-status parent, she could access high-class doña circles to find an upwardly mobile match for her son.

Understanding the historic roots of social mobility and inequality

“Historically, we know far less about the impact of mothers than fathers on the transmission of status across generations,” said Joseph Ferrie, Professor of Economics at Northwestern University. “This is a result of the difficulty in studying matrilineal family lines in contexts where women's names change at marriage. José's work cleverly fills these gaps in our knowledge and provides conclusions that will be of enduring importance."

While their study is limited to the context of 18th century Murcia, the innovative technique used by Espín-Sánchez and his co-authors offers economic historians a new tool for understanding the gender dynamics of social mobility. The terms don and doña, for instance, have equivalents in many other languages, from the French monsieur to the Italian signore, which have independent equivalents for women. Recently, Espín-Sánchez worked with students in Italy who are applying the Murcia project’s code to analyze their own historical data sets.

This research is also part of Espín-Sánchez’s broader effort to better understand the nature of economic development by conducting empirical analysis of historic sources. Previously, he studied a 700-year-old Spanish water distribution system to explore how local institutions affected water access, social justice, and poor farmers’ productivity. Currently, he is applying the Murcia project’s technique to analyze the gender dynamics of US social mobility in the 20th century – and to assess how social mobility in colonial Latin America was linked to the status of migrants’ families in Spain. Projects like these help illuminate the pre-modern systems that created and sustained inequality, in the hopes of better understanding and addressing the inequities we still face today.

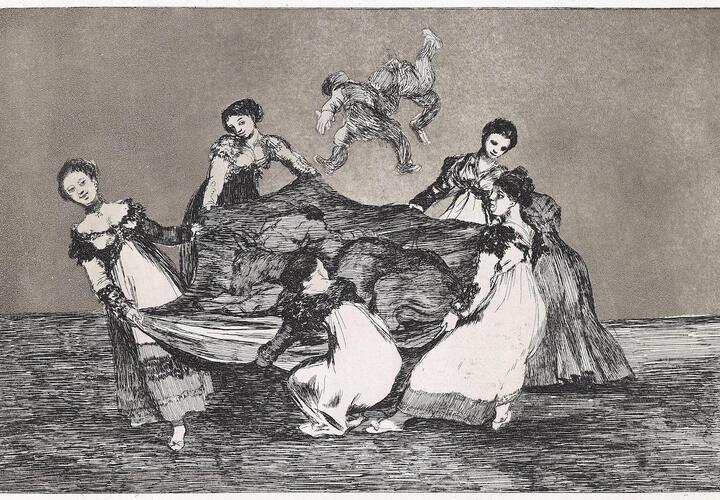

Research Summary by Clare Kemmerer. Cover image: "Pesa mas que un buro muerto," etching by Francisco de Goya (1746-1828), courtesy Wikimedia Commons.