Can well-timed access to financial products boost African farmer incomes and benefit rural communities?

In rural African grain markets, prices fluctuate dramatically, falling during harvest time and rising sharply during the ‘lean season.’ While farmers could store grain and sell it later at a profit, most smallholder farmers are unable to do so. A policy experiment in Western Kenya showed that credit constraints are a major barrier: farmers who received loans during harvest time stored more grain and took advantage of better prices later, stabilizing incomes and benefitting the broader community. However, the researchers also observed that access to credit alone provided only short-term gains. In a follow-up study, they discovered that integrating simple savings tools with loans could further boost farmers’ ability to invest, grow, and increase consumption.

Improving access to credit allows farmers to take advantage of seasonal price fluctuations in grain markets. Farmers offered loans stored 25% more grain, which increased net revenues.

Timing matters: loans offered at harvest time had the greatest impact.

Dampening price fluctuations from improved access to credit and greater storage benefitted the broader community: positive spillover effects accounted for up to 81% of overall gains in some areas.

With access to both credit and savings options, farmers invested 11% more in farm inputs and increased overall consumption by 7%.

Seasonal price fluctuations present arbitrage opportunities for farmers

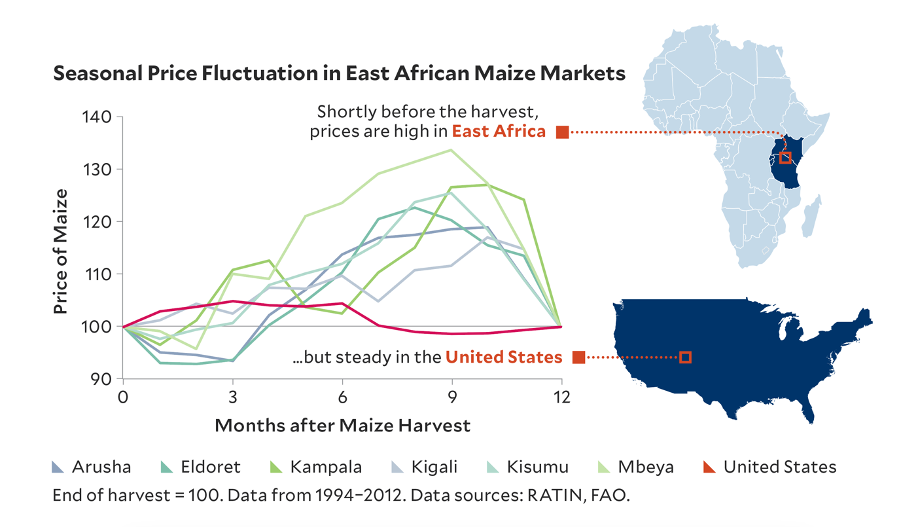

Large seasonal price fluctuations in African grain markets often imply low prices for the majority of farmers who sell immediately after harvest and high prices for consumers buying in the lean season. Prices can rise by 25–40% between the harvest and lean seasons in major markets, and by even more in remote areas.

“Rural farmers and household consumers often refer to this period as the 'hunger season,'” Bergquist, an Assistant Professor of Economics and Global Affairs, explained in an EGC interview. “Food prices are so high that people literally go hungry.”

In comparison, US grain markets see only a 5% fluctuation (see figure below). The larger increase in Africa presents an arbitrage opportunity for farmers, who could store their grain at harvest and sell (or avoid buying for consumption) at higher prices later. However, most smallholder farmers do the exact opposite, selling grain at low prices at harvest and buying it back at high prices in the lean season. Credit constraints may explain these challenges: rather than wait for prices to rise, farmers often sell quickly during harvest to cover immediate expenses like school fees.

Credit constraints prevent smallholder farmer arbitrage

In partnership with the One Acre Fund (OAF), Bergquist and her co-authors Marshall Burke and Edward Miguel conducted a two-year study in Western Kenya testing whether providing small cash loans at harvest time could enable farmers to store their grain and sell it later at higher prices. They randomized the loan offer across OAF farmer groups, then conducted high-frequency follow-up surveys three times throughout the year.

The study, published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics in 2019, showed that farmers offered loans stored about 25% more grain, with inventories jumping in the post-harvest period and gradually releasing in the lean season. While this initially reduced net maize revenues in the post-harvest period (as treated farmers held off selling their crops), they were significantly higher in the lean season as the stored maize was sold at higher prices. In total, this increased net revenues by 1,573 Ksh (US $18), yielding a 29% return on the loan.

The study also showed that the timing of the loan was key. “Access to finance is crucial, but what really matters is timing,” Bergquist said. “It's not enough to just give someone a loan – it has to be the right kind of loan, at the right time, for it to have a real impact.”

In the first year of the experiment, the researchers randomly varied the exact timing of the loan: for some, the loan was disbursed immediately after harvest in October, while for others it was disbursed right before school fees were due in January. The team observed that impacts were concentrated among the October borrowers.

At the market level, loans yield even larger community gains

To test whether this shift in sales behavior by individual farmers had an effect on market-level prices, the research team experimentally varied the density of treated farmers across locations and tracked prices at over 50 local markets. In locations where more farmers received loans, they found significantly higher prices at harvest – as more maize was stored, lowering supply – and slightly lower prices in the lean season as the stored maize was released.

This shaped the returns to the loan: revenue impacts were largest for borrowers in low-density areas, where large arbitrage opportunities remained; in high-density areas, storage by others dampened the seasonal price fluctuations that borrowers exploited. Put another way, arbitrage is most profitable when you are the only one doing it.

Conversely, for farmers who did not receive the loan, these price effects could be helpful, as they implied a higher price at harvest time – when most non-loan farmers sold – and a lower price in the lean season when most of these households bought. Bergquist and her co-authors found suggestive evidence of these positive spillovers among the control group.

“Even though these are micro-level RCTs, they have a large-scale impact,” Bergquist said. “Dampened seasonal price fluctuations in isolated rural markets have the potential to benefit entire communities – this is about more than just individual transactions.” On net, these positive spillovers to the broader community were substantial, accounting for 81% of the overall gains in high-density treatment areas, which ultimately saw larger total benefits than low-density areas.

Integrated financial products can channel farmers’ returns into forward-looking investments.

One limitation of the harvest-time loans is that they only offered short-term gains. While they helped farmers time their sales more effectively and earn higher revenues, Bergquist and co-authors did not observe any significant effects on household consumption or productive investments. This led them to question whether savings tools, when coupled with loans, could help farmers achieve longer-term growth in spending and investment.

They conducted a second follow-up study with coauthor Sanghamitra Warrier Mukherjee, published in the Journal of Development Economics in August 2024, to explore the impacts of a savings intervention that was cross-randomized with the harvest-time loan. To a randomly selected sample of farmers, they offered a simple savings tool: a metal lockbox stored in their home. Outside their intervention, two-thirds of respondents reported having no formal savings accounts. The researchers’ goal was to understand how credit and savings can complement each other to increase consumption and investment.

They discovered that although the lockbox did not alter the returns to the loan (it had no effect on maize revenues), it did affect how farmers channeled loan returns. Farmers who received both the loan and the lockbox invested 11% more in farm inputs and saw 7% higher consumption. The consumption boost was especially pronounced during the lean season. They did not observe any effect of the lockbox on its own.

Potential implications

For policymakers, the findings from this research highlight the critical need for a more nuanced and integrated approach when designing financial products for rural communities in low- and middle-income countries:

1. Timing matters: Rural economies are shaped by harvest-driven seasonal fluctuations, which result in large price and consumption swings. Financial products should be tailored to align with the specific timing of farmers’ income and expenses.

2. Integrated financial approaches can be complementary: Poor households often lack access to both the credit products needed to exploit economic opportunities and the savings vehicles needed to channel resulting profits into forward-looking investments. Providing households with complementary credit and savings products could be particularly effective.

3. General equilibrium effects can shape size and distribution of the returns to financial access: In isolated and rural markets, prices can respond to changes in local supply and demand. These price responses can shape the returns to financial access. In the context of the study, they resulted in damped seasonal price fluctuations, which shifted the benefits of credit from direct recipients to the broader community.

“The overarching theme of this research is how finance interacts with local markets – specifically, how it affects rural agricultural economies,” said Bergquist. As an extension of these research questions, she is currently working on a large-scale randomized controlled trial studying a mobile marketplace in Uganda to connect buyers and sellers of agricultural commodities.

“It’s designed to reduce search costs, a potentially important component of trade costs,” she said. “The results have some parallels to what we see in the maize storage project, though they’re about arbitrage across space rather than time. We find that prices in surplus areas rise but drop in deficit areas. These results show how interventions can affect both producers and consumers.”

Research summary by Devina Aggarwal. Infographic by Nils Enevoldsen and Goodness Okoro.