How an EGC collaboration with South Asian economists in the 1960s yielded era-defining research

In the 1960s, members of EGC's founding team connected with economists in Pakistan as they founded the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. PIDE’s engagement with EGC fostered innovative research including the influential Fei-Ranis model of economic growth.

By Adena Spingarn

United Pakistan was established after the partition of British India in 1947, and consisted of two culturally and geographically distinct regions with their own local economies and languages, separated by a thousand miles of Indian territory. With the creation of the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) a decade later as a center for economic training and development research, the nation invested in building its capacity for economic research that would guide policy.

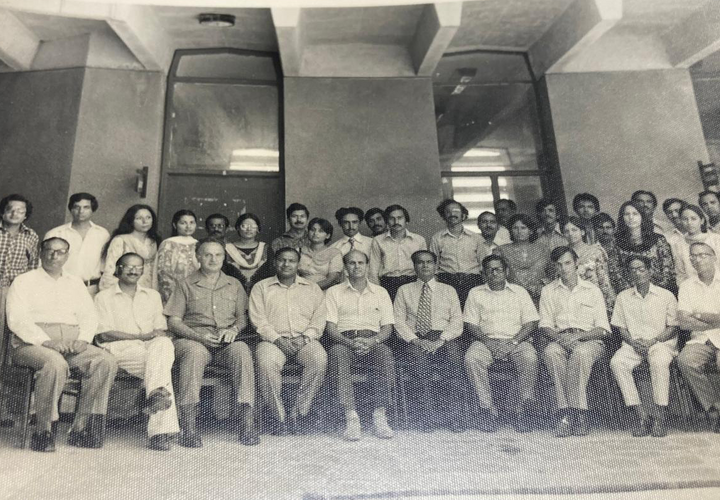

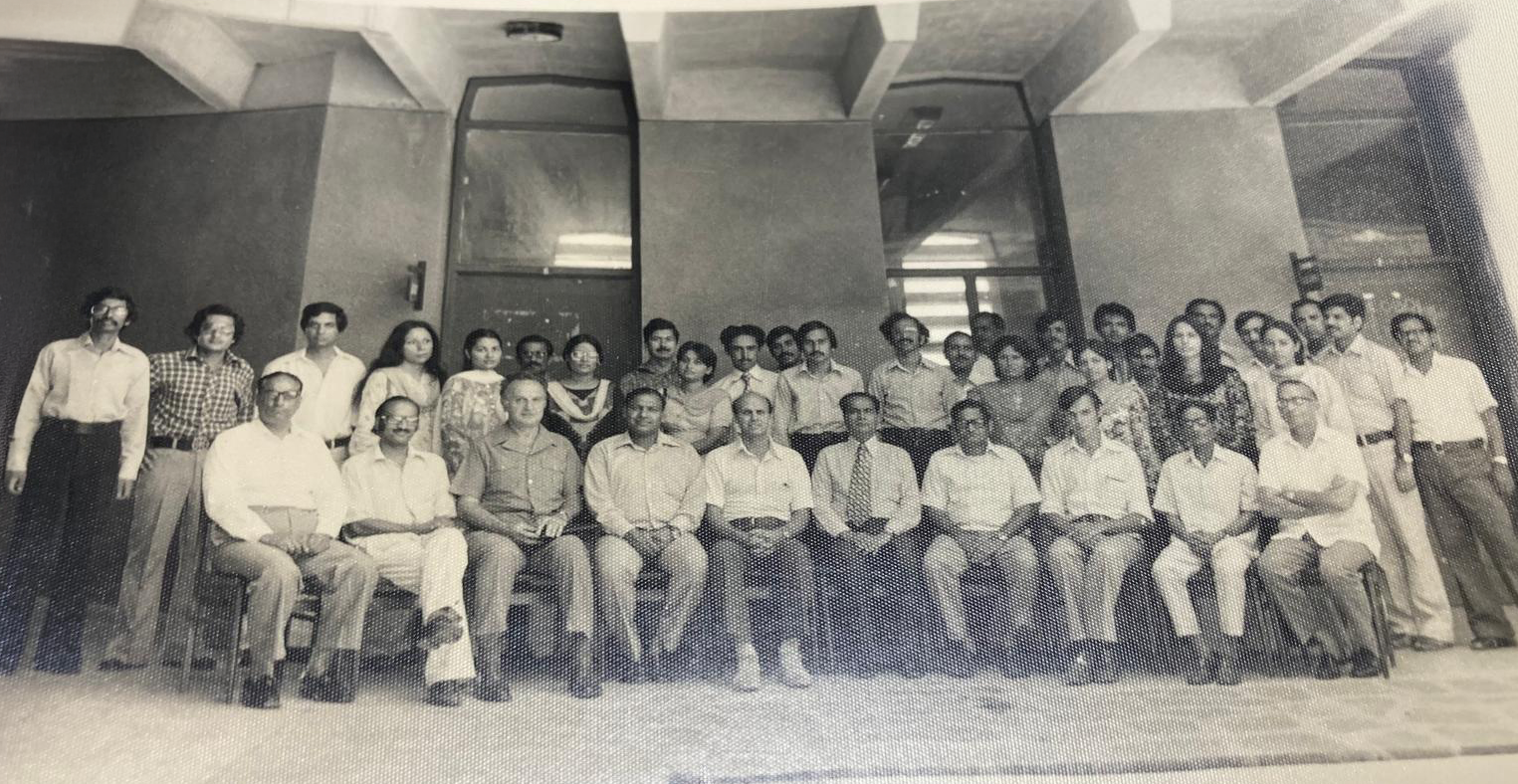

A group of scholars seated around Director Mr M L Qureshi (center, in tie), who was responsible for resurrecting PIDE in Islamabad in the 1970s.

The Yale Economic Growth Center (EGC) and PIDE were both initially funded by the Ford Foundation to encourage productive cross-country exchanges on economic growth among economics experts and support the training of early-career economists from lower-income countries. With Ford’s support, EGC sent senior scholars to Karachi to collaborate with Pakistani counterparts and help make PIDE a world-class center for development research. PIDE nurtured seminal research for economists who continued their work in present-day Pakistan as well as those who became key figures in independent Bangladesh (previously East Pakistan) after 1971. Today, PIDE is located in Islamabad and serves as one of Pakistan’s premier centers for applied economic research and as a degree-granting institution training a new generation of development researchers.

EGC affiliates including John Fei, Gustav Ranis, and the Center’s founding director Lloyd Reynolds visited Karachi and helped establish the institute’s research and training programs. They collaborated with PIDE staffers in creating flow diagrams –visual models of the movement of money, goods, and services through the nation’s economy – and input-output tables showing how the nation’s largest industries interacted with each other and the economy. PIDE, in turn, became a fruitful site for EGC research. Conversations between Fei and Ranis while both were in Karachi generated fresh insights and produced the now-famous Fei-Ranis model of economic growth, which suggests that nations can boost productivity by shifting labor and resources from agriculture to the industrial sector. The model was published in 1961 as “A Theory of Economic Development” in the American Economic Review. EGC affiliates contributed articles to the Pakistan Development Review, an international academic journal that has published theoretical and applied research in development economics, and on Pakistan in particular, since 1961.

Faisal M. Ansari, Flickr

Faisal M. Ansari, Flickr

A view of the Headquarters of the State Bank of Pakistan on I. I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi, in the 1960s.

Training a new generation of development economists

When Azizur Rahman Khan first arrived at the PIDE Karachi offices as a young student in 1960, he found John Fei playing a lunchtime game of ping pong at the tables set up in the center of the Institute’s large, open corridor. Fei, the “real champion” player at PIDE according to Khan, interrupted his game to welcome the new arrival from East Pakistan.

Khan had completed doctoral studies abroad through the Ford Foundation’s Overseas Scholarship Program, a program open to staff from PIDE and other academic and research institutions. Running from the 1960s through 1971, the program helped PIDE attract some of the nation’s strongest students, many of whom then continued their careers at PIDE.

Although located in Karachi, most of PIDEs staff – and many of the students supported by Ford’s study abroad program – came from East Pakistan, a region with a strong tradition of education and intellectual debate. Because the seat of political institutions was primarily in West Pakistan, West Pakistanis had greater access to lucrative government and private sector jobs, and were less likely to pursue Ford fellowships.

During the 1960s, PIDE research made significant contributions to the field of development economics by showing that united Pakistan’s economic policies, which reflected then-dominant theories of economic growth, produced greater inequality, especially between East and West Pakistan. This attention to the way that economic growth could augment inequality put PIDE’s research at the forefront of a broader investment by development economists in equitable and inclusive growth.

Although PIDE research was sometimes at odds with the policies of Pakistan’s governments of the 1960s, the Institute was able to continue as an autonomous research organization because the country’s leaders saw the value of having a well-regarded academic institute in the country and assumed that academic research would steer clear of politics.

“The two sides understood the rules,” Khan wrote in a 2010 reminiscence published in the Pakistan Development Review. “…PIDE understood that the price of [its] autonomy was self-imposed distance from politically sensitive controversies.”

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

On June 7, 1966, the people of what was then East Pakistan observed a general strike in support of the Awami League's Six-Point program of autonomy.

Birthing a new nation – and an institution

As the economy of united Pakistan grew, some East Pakistani analysts suggested that this growth favored West Pakistan over East Pakistan. A growing separatist movement led by the Awami League called for increased political autonomy for East Pakistan as well as greater equity in the distribution of government funding and foreign aid.

Some East Pakistanis also proposed moving some of the nation’s institutions, virtually all of which were in West Pakistan, to the East. In 1970, the government agreed to move PIDE from Karachi to Dhaka, and the furniture, library, and staff soon relocated. Although there was a tentative plan to maintain PIDE’s presence in West Pakistan, it wasn’t clear who would work there given the paucity of economists from that region.

In December of 1970, Pakistan held its first direct general elections – and the Awami League won decisively. But the military junta led by Yahya Khan refused to cede power, and political unrest turned to civil war on the streets of Dhaka. Virtually all PIDE’s staff – having relocated from Karachi just months before – fled the city.

When Bangladesh gained independence in 1971, Pakistan lost its premier economic research institution: PIDE remained in Dhaka and resumed operations as a Bangladeshi institution, ultimately named the Bangladesh Institute for Development Studies (BIDS). The change was so rapid that staffers used PIDE letterhead with “Pakistan” crossed out and “Bangladesh” written by hand.

With most of PIDE’s physical assets and staff remaining in Dhaka, and some of the few West Pakistani staff members held in India as prisoners of war, there were significant obstacles to reorganizing. But PIDE soon started to rebuild at a new location on the campus of the University of Islamabad (renamed Quaid-i-Azam University in 1974).

Rebuilding PIDE

The next several decades were a challenging period for PIDE. Although funding from the government of Pakistan continued after 1972, outside funds decreased substantially during the 1970s and 80s: the Ford Foundation withdrew funding completely by 1975, and others including the U.S. Aid for International Development and the United Nations Development Program also reduced their funding.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the government of Pakistan limited its PIDE funding to 75 percent of the institution’s expenses and asked PIDE to raise the other 25 percent from consulting work for national and international organizations. “It became more and more of a consulting firm,” said Pakistani economist Sohail Malik, a PIDE staffer during the 1970s.

Nevertheless, PIDE maintained its academic ties through the continued publication of the Pakistan Development Review as well as the 1982 formation of the Pakistan Society of Development Economists, which has continued to host an annual conference that draws prominent researchers from all over the world, including many Nobel laureates.

In the early 2000s, PIDE leadership identified an opportunity for Pakistani economists trained abroad “to transfer their knowledge to the young generation,” according to Nasir Iqbal, Associate Professor and Acting Dean at PIDE. In 2006, PIDE became a degree-granting institution focused on building Pakistan’s local development research capacity. PIDE awards Master’s degrees in several economics-related fields, including Public Policy and Development Studies, as well as PhDs in Economics and Econometrics. In recent years, Pakistan’s government has strengthened its commitment to PIDE by funding 95 percent of its budget, according to Iqbal.

This resurgence of government support has been accompanied by a shift in the institution’s research agenda toward more applied policy analysis. “Now we directly try to engage with the ministries,” Iqbal said. Current projects include working with the Ministry of Energy and Power on tariffs and with the Ministry of Planning, Development, and Special Initiatives to revisit annual development plans.

“PIDE plays a very significant role in terms of redefining government priorities, redefining the growth agenda, and redefining short, medium, and long-term strategies to revive growth,” he said.

To Shan Aman-Rana, a Fall 2024 EGC visitor who was a Pakistan Administrative Services bureaucrat in Pakistan before earning a PhD in Economics and is now Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Virginia, collaborations like the one between EGC and PIDE in the 1960s are vital sources for development research.

“I hope to see this collaboration continue and grow, strengthening the role of institutions like PIDE as hubs for cutting-edge research and amplifying the voice of local researchers in developing countries,” she said. “I look forward to seeing the next generation of economists emerge from these spaces – driven by curiosity, committed to impact, and equipped to tackle the challenges that shape millions of lives.”