How Nurul Islam, one of Bangladesh’s founding economists, found intellectual refuge at Yale

As economic inequality between East and West Pakistan fueled a growing separatist movement for a free Bangladesh during the 1960s and early 1970s, EGC collaborated with Nurul Islam and his fellow development economists at the Pakistan Institute for Development Economics – and provided an academic home for Islam and his family when they were forced to flee political violence.

By Adena Spingarn

In the recent protests in Bangladesh against now-resigned Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, some may see echoes of the violence and chaos of 1971, when demonstrations by political dissenters including Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, led to a war for the independence of Bangladesh. Although 50 years separate them, these protest movements share a common target: a government imposing an inequitable economic system. Today, demonstrators largely oppose employment quotas and government corruption that reduce opportunities and freedom; then, citizens objected to an oppressive government that promoted economic growth in West Pakistan – today’s Pakistan – at the expense of East Pakistan – today’s Bangladesh.

The protesters of 1971 understood the economic disparities in united Pakistan due to the scholarship of many Bengali economists of that era, including Nurul Islam. His work on the national economic policies that widened disparities between East and West Pakistan was supported by collaboration with colleagues from the Yale Economic Growth Center (EGC) – where he also found an academic home during the months of 1971 when he was forced to flee East Pakistan under threats to his life from the military junta. “My father immediately had a family there," said Roumeen Islam, daughter of Nurul Islam, of EGC. She is now Senior Economic Advisor to the Managing Director of the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank Group.

Before and after his collaboration with Yale, Nurul Islam was a prominent economist and teacher, mentoring many, including Muhammad Yunus who would go on to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 and to lead Bangladesh’s interim government today. Islam died last year at age 94.

“[Islam’s] crucial economic analysis provided the intellectual basis for East Pakistan’s desires for greater economic and political autonomy,” said Mushfiq Mobarak, the Jerome Kasoff ’54 Professor of Management and Economics at Yale and an EGC affiliate, adding that his research on Bangladesh’s contemporary social and economic development builds on the work of Islam and his contemporaries. “This translated into a separatist movement, and finally led to the birth of a new nation.”

Developing an economic critique of united Pakistan

Born in 1929 in Chittagong, in what was then British India, Nurul Islam grew up in a middle-class family. An exceptional student, he earned his PhD from Harvard in 1955 and returned to take a position as Professor of Economics at the University of Dhaka in East Pakistan, eventually serving as Department Chair. Much of Islam’s research focused on the national economic policies that encouraged the economic growth of West Pakistan at the expense of East Pakistan. Early in his career, Islam helped develop what became known as the “two-economy theory” of economic disparities between East and West Pakistan, which suggested that government policies had created such severe inequalities between East and West Pakistan that it was as if the regions had two different economies.

The Pakistan Institute for Development Economics (PIDE) was a research institute with the dual mission to conduct quantitative, policy-oriented research and to promote the training of Pakistani economists. Established in Karachi, West Pakistan in 1957 with funding from the Ford Foundation, PIDE was initially led by American economists including Gustav Ranis, who would go on to serve as EGC’s Director, and Mark Leiserson, who in 1962 took his wife and five children to Karachi for a two-year sabbatical from Yale. The Ranis and Leiserson families became lifelong friends to Nurul Islam and his family.

Islam became director of PIDE in 1964 in line with the Ford Foundation’s requirement that a qualified Pakistani economist take over leadership of the Institute. His appointment by the united Pakistan government despite the controversial political implications of his work was the result of a number of factors, among them that West Pakistani economists, who had greater access to the higher salaries and social power of jobs in government and finance, were not interested in research or an academic position. Islam, who was recruited by EGC’s Gustav Ranis, was acceptable to government leaders because they believed that, as Islam later wrote in an autobiography, “in the non-descript position as the Director of PIDE, I would have no role to play in the political economy of Pakistan.” This would turn out to be far from the case.

During the late 1960s, Islam and PIDE’s primarily East Pakistani economists – many had been trained in research methodologies under his influence at the University of Dhaka – continued to develop critiques of the economic and political structure of united Pakistan. This research would inform the economic rationale for the independence of Bangladesh. “Under Nurul's leadership,” recalled Islam’s friend, economist Rehman Sobhan, “this group of Bangalees at PIDE constituted a veritable think tank of policy ideas which fed the agendas for self-rule for East Pakistan and incubated further policy options for the germinating state of Bangladesh.”

In 1966, Islam led other dissenting economists including Sobhan and Anisur Rahman (who would shortly head to EGC for a year-long visit) in drafting the League’s Six-Point Program for a more equitable distribution of power and resources between East and West Pakistan.

EGC affiliates contributed to this work not only by advising research at PIDE as visiting advisers in Karachi, but also by inviting Nurul Islam to spend 1967-68 at Yale.

“My father spoke really fondly of his time at Yale,” said Islam’s daughter, Roumeen Islam. “Though he went into government later, he was really an academic at heart. He loved arguing for argument’s sake, just to get to the truth of the matter.”

The research Nurul Islam conducted and presented at EGC that year included a critique of the system of trade controls intended to balance imports and exports, which Islam showed harmed economic growth and widened income disparities between East and West Pakistan.

While Islam was visiting EGC, tensions between united Pakistan President Ayub Khan and Awami League leaders grew. When Islam returned to Karachi, a massive student uprising emerged in East Pakistan to protest the military government’s repressive rule.

Islam, whose critique of the united Pakistan government had until now been confined to economic planning, became more politically involved. He became a leading economic advisor to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, leader of East Pakistan’s Awami League, who after independence would become president and prime minister of Bangladesh, and joined him in negotiations with the president in the Spring of 1969, as student demonstrators clashed with government forces in the streets.

With the approach of the 1970 election – the first and ultimately only direct general election in united Pakistan – Islam intensified his public support of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the Awami League. He took the lead in drafting the League’s 1970 pre-election manifesto, which detailed how to apply the Six-Point Program to united Pakistan’s constitution.

Meanwhile, Islam met with EGC leaders Gustav Ranis and Lloyd Reynolds in Karachi in December 1970 to discuss future collaboration between PIDE and EGC. Notes from their meeting report that Islam was “very keen on more research collaboration between PIDE and EGC” and floated ideas that could be proposed in the next Ford grant application: bringing more PIDE people to Yale, funding research in Pakistan through EGC, “[m]aybe a joint PIDE-EGC conference every couple of years.”

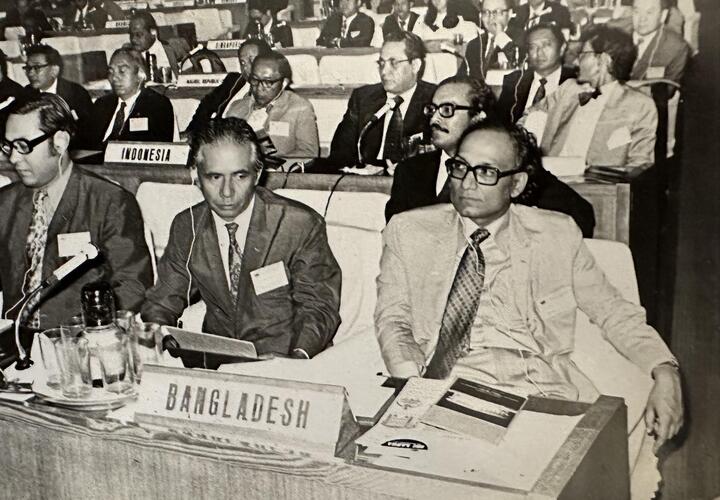

Photo courtesy Roumeen Islam.

Photo courtesy Roumeen Islam.

Nurul Islam and his wife, Rowshan Ara.

An independent Bangladesh

Although Islam was now seen as an enemy of the ruling regime, Ayub Khan’s successor Yahya Khan and his cabinet recognized that they needed to make some concessions to East Pakistan. One of the Awami League’s demands was to move some of the nation’s institutions, which were then all clustered in West Pakistan, to East Pakistan. The new government agreed to Nurul Islam’s proposal to relocate PIDE from Karachi to Dhaka. According to Islam’s contemporary Sobhan, this move from West to East Pakistan “was seen as a low-cost gesture by the military regime to appease the Bangalis.”

Nevertheless, the 1970 elections brought chaos to the region as Yahya Khan’s military junta refused to cede power to the Awami League despite its sweeping victories in East Pakistan’s national and provincial elections.

Recognizing the economic arguments that undergirded East Pakistan’s resistance, the military targeted PIDE economists including Islam, who went into hiding only a day before his home was ransacked by the army. Political turmoil put a pause on the institutional collaboration between EGC and PIDE, as the army of Pakistan occupied Dhaka and virtually all of PIDE’s staff fled for safety. As PIDE economist Swadesh Bose reported in a letter to Lloyd Reynolds, “[f]or all practical purposes the Institute was non-functioning during the period of March through December 1971.”

With ongoing threats to the freedom and lives of those who called for the liberation of Bangladesh, development community leaders worried about the physical safety of Islam and other dissenting economists. In May 1971, Gustav Ranis, now EGC Director, persuaded the Ford Foundation to add funds to the EGC’s upcoming two-year grant in order to provide Nurul Islam with a safe place in New Haven to live and work. Although Ford had rejected Ranis’ request for increased funding for EGC operations only days earlier, the foundation now added a one-time increase of $40,000 to cover Islam’s “salary, travel, and related expenses” while he spent a year at EGC.

Islam arrived in the US in May 1971. Ranis and a Ford Foundation officer were waiting for him at the airport. Islam’s wife and two children, having escaped separately via Paris, joined him in New Haven a few months later.

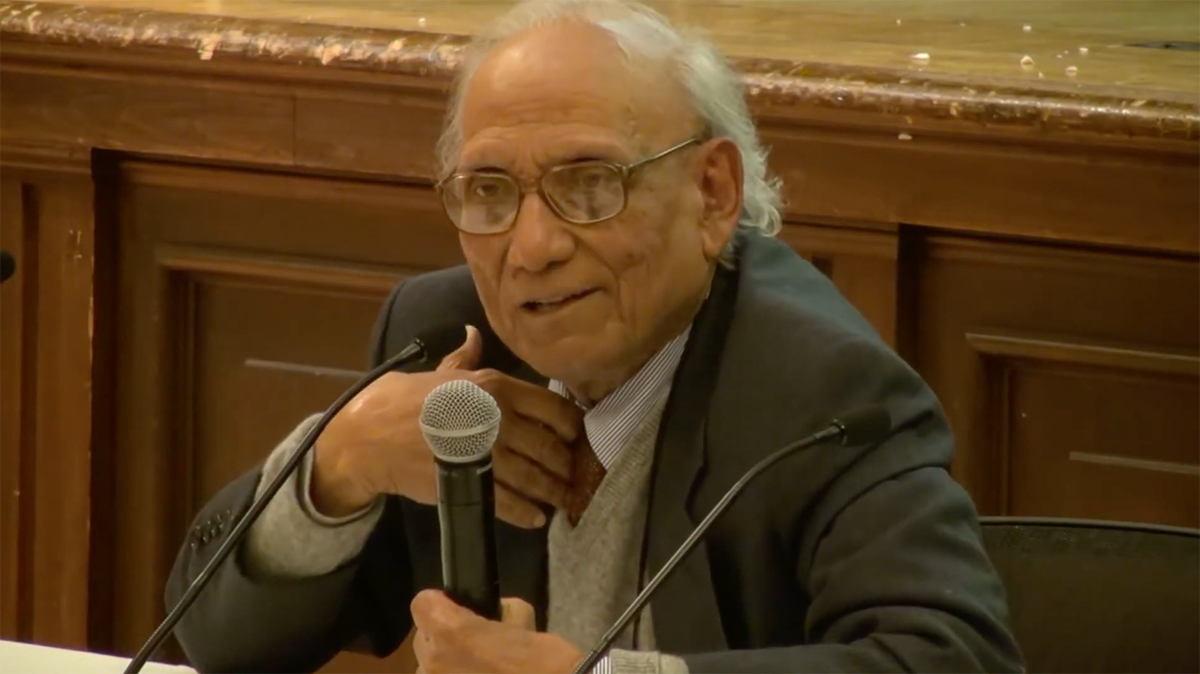

"We economists know the ingredients of economic growth, but we don't know the recipe."

Nurul Islam speaking at the presentation of the Lifetime Achievement Award from by Bangladesh Development Initiative (BDI) in 2015.

Roumeen Islam recalls her family’s gratitude to the EGC community during this time. “They really supported him,” she said. “EGC gave us a place to be.” Nearly every weekend, the Islam family would share a meal with the Ranises at one or the other’s home.

In New Haven, Islam spent much of his time rallying the international community to Bangladesh’s cause and meeting with American policymakers to encourage them to halt financial support of Pakistan.

Bangladesh achieved independence in December 1971. Islam, who had done so much to bring about this new country, watched on television as the Pakistan Army surrendered in Dhaka. Excited to join in the formation of the new nation of Bangladesh, he left New Haven a day or two later, just seven months after arriving.

As a cabinet minister and head of Bangladesh’s first planning commission, Islam was charged with setting up and running the nation’s economy. After three years of policymaking, Islam was ready for a more academic life, and in early 1975, he left Karachi with his family for a short-term fellowship at Oxford. While he was abroad, a coup in Bangladesh prevented his return to his country. However, the system he put into place formed the basis for the country’s exceptional economic growth; at its birth, Bangladesh was the second poorest country in the world, but its growth over the next fifty years made it “one of the great development stories,” according to the World Bank.