Towards Gender Equality Newsletter Issue #3: Laws and Gender Equality

It is quite stunning to reflect on how just under 80 years ago – and on the eve of independence from British colonial rule in India – the status of women in my home country was remarkably different. Only six percent of women were literate, the average woman was married at age 15, and 2,000 women died for every 100,000 live births. A lot has changed since then.

To start with, women and men obtained equal voting rights as India started democratic self-governance in 1947. There have been hard-won legal rights, and measurable changes in the economic and social well-being of women since then, in India and the rest of the world. And yet, certain fundamental legal reforms towards gender equality remain politically out of reach. The burgeoning literature on the “mutual interaction of economic and legal changes” (Doepke et al, 2012; Tertilt et al, 2024) showcases the ways in which economic development and legal gender equality interact and evolve. In this issue of our newsletter, we highlight a number of emerging insights on this theme for research and policy consideration.

Aishwarya Lakshmi Ratan

EGC Deputy Director

Research Highlight

Gendered Laws and Women in the Workforce

Hyland, Djankov & Goldberg [Journal Article]

This paper by EGC Affiliate Professor Penny Goldberg with co-authors Marie Hyland and Simeon Djankov sheds light on legal inequality between women and men with respect to economic opportunity, and how these inequalities have evolved over the past half century. The authors use the World Bank's Women, Business and the Law database to illustrate inequalities between genders on pay, treatment of parenthood, and a range of other variables. In the paper, the authors establish the following stylized facts.

Stylized Fact 1: A woman in the average country has three-quarters the rights of a man

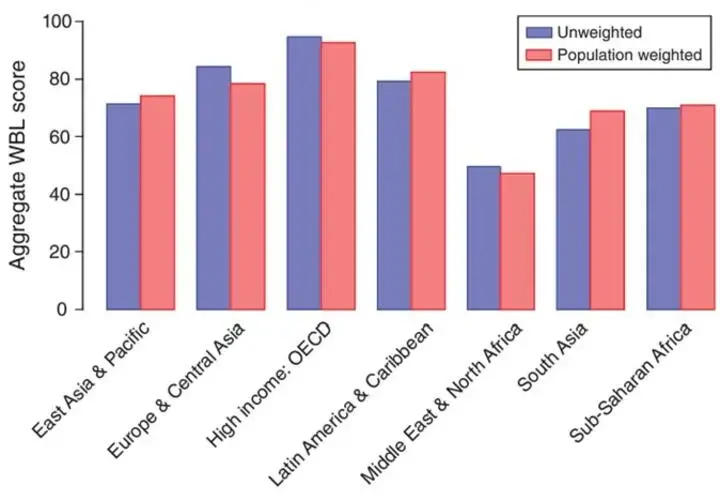

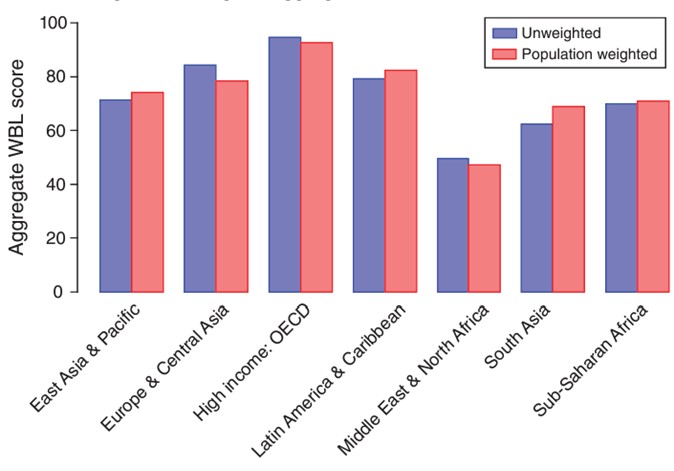

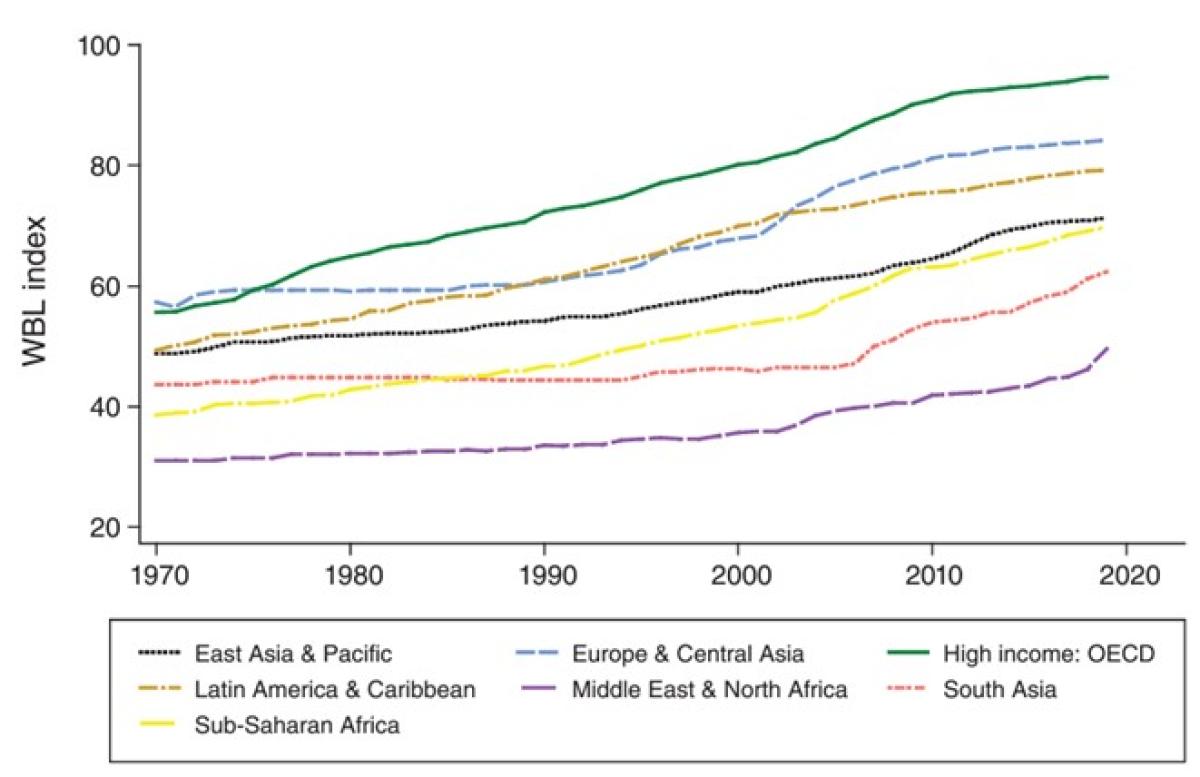

In 2019 the global average Women, Business and the Law (WBL) population-weighted score was 74.4 out of 100 points (75.2 out of 100 using population-unweighted country scores), indicating that women are accorded about three quarters the number of rights as men. There is also significant variation by region in legal gender equality, as illustrated by Figure 1.

Source: Hyland, Marie, Simeon Djankov, and Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg. 2020. "Gendered Laws and Women in the Workforce." American Economic Review: Insights, 2 (4): 482. Copyright American Economic Association; reproduced with permission of the American Economic Review: Insights

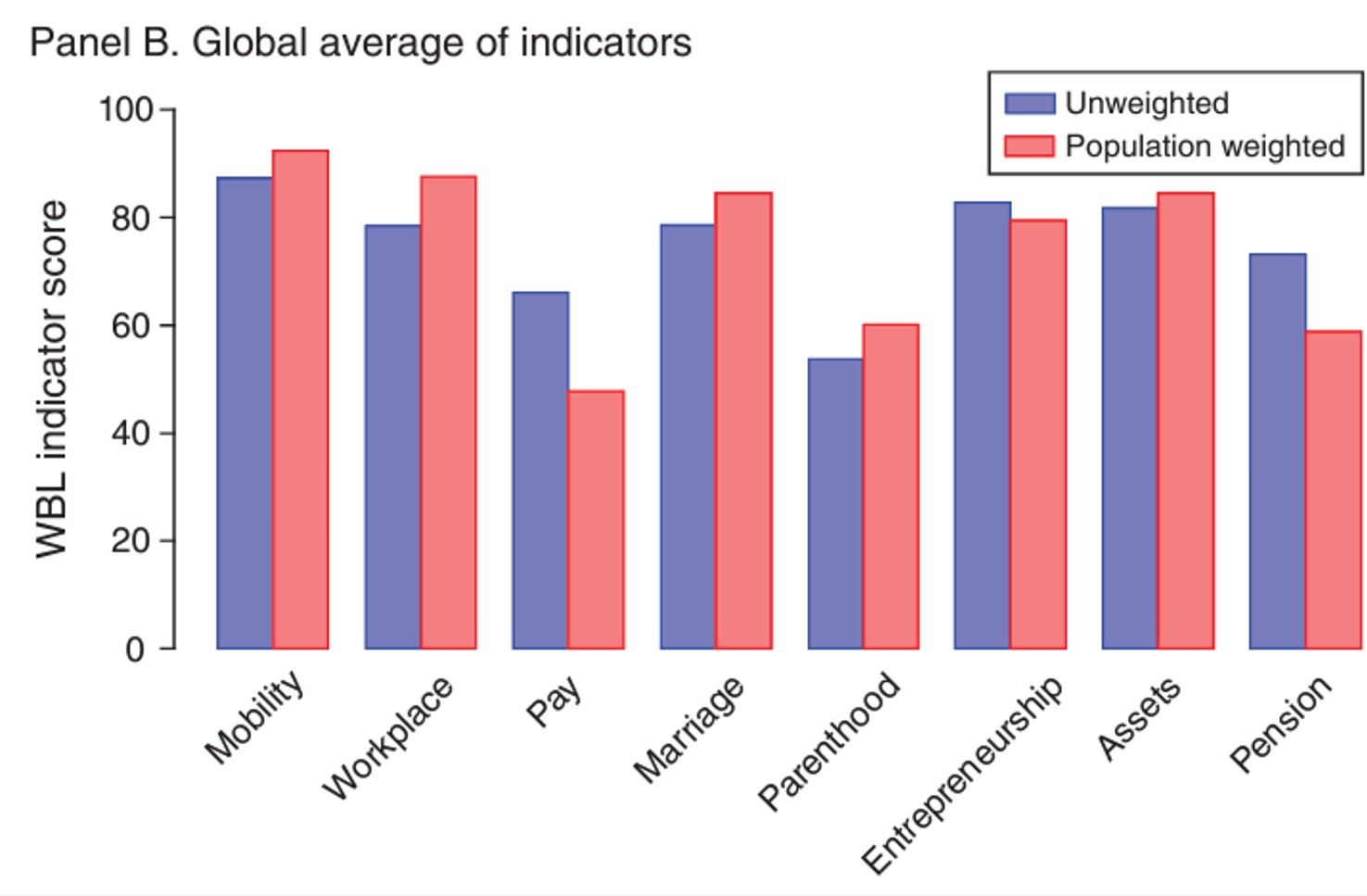

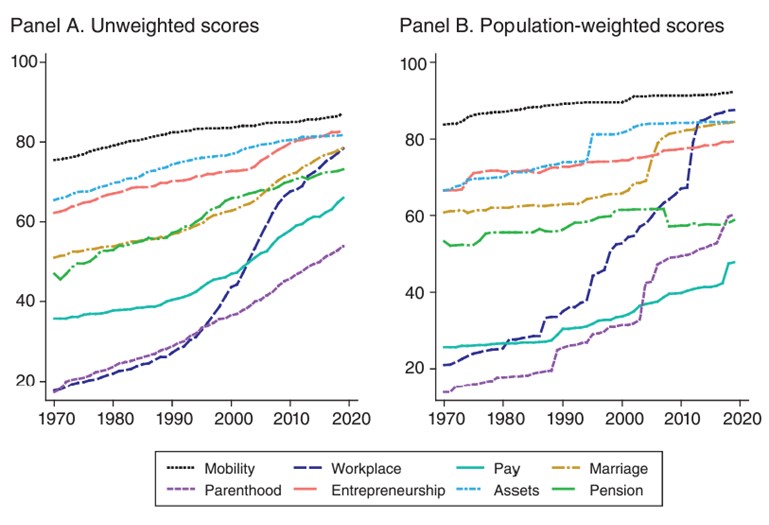

Stylized Fact 2: Women are most severely penalized when it comes to laws related to having children and getting paid

There are significant differences in the WBL score between the eight indicators covered. Figure 2 shows that for population-weighted WBL scores, women are most disadvantaged on equal pay laws. Conversely, mobility laws show the lowest level of gender inequality.

Source: Hyland, Marie, Simeon Djankov, and Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg. 2020. "Gendered Laws and Women in the Workforce." American Economic Review: Insights, 2 (4): 482. Copyright American Economic Association; reproduced with permission of the American Economic Review: Insights

Stylized Fact 3: The last five decades have seen tremendous progress, but the pace of reform has differed across regions

As Figure 3 shows, whilst unweighted global WBL score has increased almost 30 percentage points from 46.4 to 75.2 in the five decades leading up to 2019, different regions have progressed at different paces.

Source: Hyland, Marie, Simeon Djankov, and Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg. 2020. "Gendered Laws and Women in the Workforce." American Economic Review: Insights, 2 (4): 483 Copyright American Economic Association; reproduced with permission of the American Economic Review: Insights

Stylized Fact 4: The pace of reform varies not only across countries but also across individual indicators

Figure 4 illustrates progress on each of the indicators both when reforms are unweighted (panel A) and weighted by population (panel B). The Workplace indicator improved the most, yet the pay indicator still lags behind, despite starting from a relatively low base.

Source: Hyland, Marie, Simeon Djankov, and Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg. 2020. "Gendered Laws and Women in the Workforce." American Economic Review: Insights, 2 (4): 486 Copyright American Economic Association; reproduced with permission of the American Economic Review: Insights

Stylized Fact 5: Legal gender equality is positively correlated with women’s outcomes in the labor market

Results from OLS regressions show that the WBL index correlates with real economic outcomes. An increase of one point in the WBL index correlates with a 4.1 percent rise in female labor force participation and a 6.7 percent decrease in the gender wage gap.

New Research

Drivers of Change: How Intra-household Preferences Shape Employment Responses to Gender Reform (2023)

In this study, a field experiment measures how Saudi Arabia’s lifting of a driving ban for women affects their employment and agency. After two years women in the treatment group are 61% more likely to drive and 35% more likely to be employed, but 19% more likely to require permission to make purchases. The results show how intra-household responses to gender reforms can work to offset progress on legal equality for women.

Lawful Progress: Unveiling the Laws that Reshape Women's Work Decisions (2023)

In this IMF Working Paper, the authors study the impact of women’s legal rights on labor force participation decisions made by women and men. They do this with a detailed analysis of 35 gendered laws, and find nine key laws that can promote female labor force participation, including laws related to household dynamics and women’s agency within the family, such as divorce and property rights laws, and laws regarding the ability of women to travel outside the home.

Podcast: Why women in India are dropping out of the workforce

In this episode of Voices in Development, Farzana Afridi, a Professor of Economics at the Indian Statistical Institute in Delhi, and Kanika Mahajan, Associate Professor of Economics at Ashoka University in Sonepat, India, discuss their research collaborations on women and work, the benefits and risks of digital platforms for women in India, and how researchers can influence policy.

Featured Researcher: Antonia Paredes-Haz

Antonia Paredes-Haz is a Postdoctoral Researcher at Berkeley Haas and completed her PhD in economics at Yale University in 2023. She studies gender representation in politics, working in the fields of political economy and development. Antonia’s job market paper is titled “Gender quotas and strategic voters: Experimental evidence from Chile’s constitutional convention”.

In it, she examines the impact of a gender quota that enforced gender parity in candidates and representatives for the election of Chile’s constitutional election. To do this, she randomizes the rollout of a voter information campaign. She finds that voters responded by switching their vote to the gender favored by the quota requirement and reduced their votes for low-competency men. Overall, her findings support the use of electoral mandates that, when well-designed, can increase the average legislator's competence and the extent to which policy-making processes reflect voter preferences.

Antonia is also collaborating with Ceren Baysan, Carlos Molina, and Gamze Zeki on a paper assessing voter preferences for progressive gender equality policies in Turkey. Working with two political parties, they randomize at the neighborhood level two types of door-to-door campaign promises: one on issues related to women (female labor participation and domestic violence) and one on a party-chosen theme. By comparing vote shares among neighborhoods exposed to those two campaigns to a control group that is not exposed to any door-to-door campaign, they assess the return on gender equality campaigning.

See Antonia’s website for more information.

"I choose to focus on female representation because I believe democracies have limited power to represent their citizens' perspectives unless they broaden their representation, including more women in positions of power. Women are underrepresented in politics worldwide, and governments are actively seeking measures to improve their representation. As a researcher, I believe that studying these issues would help us design better public policies and enhance the lives of women, particularly in developing countries."

- Antonia Paredes-Haz

Policy Engagement, Events & Media Coverage

Upcoming event: Gender and Growth Gaps in India - Research and Policy Dialogue (August 8, 2024)

Join us in New Delhi for a day-long dialogue investigating gender as a dominant friction in India’s labor markets and exploring how policy can address this friction to better enable the country’s economic transformation. This will be the second event focused on South Asia organized under the global ‘Gender and Growth Gaps’ project, housed at the Yale Economic Growth Center, and builds on learnings from our first workshop held in August 2023 in Bengaluru. The event will also include a training and mentoring workshop held on Friday August 9, 2024, at the Institute of Economic Growth.

Women in India Face a Jobs Crisis. Are Factories the Solution?

EGC Director and Inclusion Economics lead Rohini Pande was cited in a New York Times article, which highlighted that as multinational brands shift factory production from China, Indian women – long shut out of the workforce – could be prime beneficiaries. The article explores how to connect women with the jobs they want, given social norms limiting their mobility. In the article, Rohini stated, "In all the surveys we see, women want to work but find it very difficult to migrate to where the jobs are, and the jobs aren’t coming to them".

Gender and Growth Gaps in Sub-Saharan Africa – Research and Policy Dialogue (June 13, 2024, Accra, Ghana)

The Gender & Growth Gaps in Sub-Saharan Africa: Research & Policy Dialogue took place on June 13 in Accra, Ghana. The workshop included three plenary sessions in which brief research presentations were followed by panel discussions that included research, policy, civil society, and industry experts. In the opening keynote dialogue, former gender Ministers Hon. Williametta Saydee-Tarr from Liberia and Hon. Nana Oye Bampoe Addo from Ghana gave their perspectives as senior policymakers. The main plenary sessions focused on Macroeconomic Growth Strategies and Gender Gaps in Key Labor Market Indicators; Gender & Power: From the Household to Institutional Structures; and The Rise of the Digital Economy.

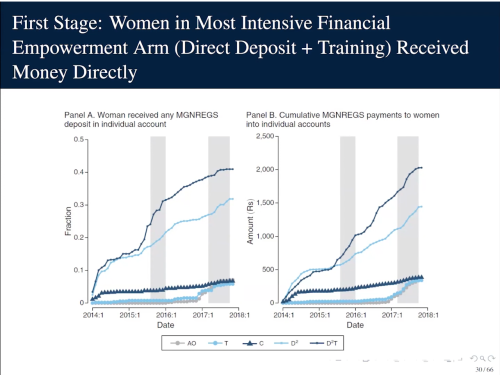

Building Resilience through Inclusive Safety Nets: Empowering Marginalized Women (May 10, 2024, webinar)

As part of the USAID Agency Learning and Evidence Month 2024, Charity Troyer Moore, Scientific Director at Inclusion Economics, presented findings on the effects of design changes that can make India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), the world’s largest workfare program, work better for women – with implications for similar policies around the world.

Additional Resources

Women, Business and the Law 2024

Women, Business and the Law (WBL) 2024 is the 10th annual edition of the World Bank series of studies that track the extent to which laws facilitate women’s equal economic opportunity in 190 countries. This year’s version presents two sets of data. WBL 1.0 focuses on the core index of eight indicators of women’s legal empowerment. An expanded version, WBL 2.0, measures the gap between the presence of laws, or de jure equality, and how these laws function in practice, contributing to de facto legal equality. WBL 2.0 introduces two new indicators, which are Safety and Childcare, and also revises the existing indicators.