Understanding FLFP

Generally speaking, at low levels of economic development, poverty leads women and men alike to work low-wage jobs, particularly in agriculture. As an economy grows, men become more educated, get better jobs, and bring more money home. It could be that in such situations women favor staying at home over getting non-agricultural jobs that are relatively low paying, or it could be that women, whose education has historically lagged behind men’s, come second to men in accessing these jobs. At more advanced stages of development, average household income continues to rise – and with it the education women attain and quality of jobs they can successfully compete for.

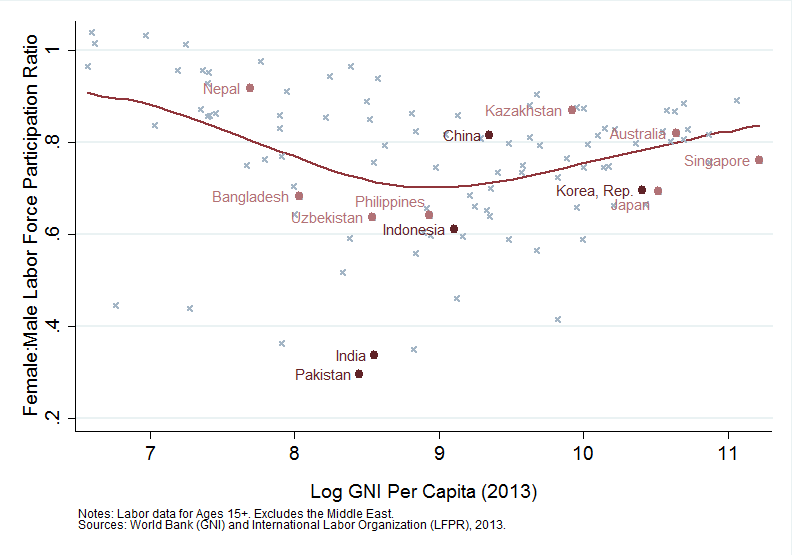

The U-shaped curve gives us a framework to spot cases where a nation’s FLFP stagnates when we would expect it to rise. If you look at the graph above, India and Pakistan are clear outliers with FLFP rates far below their economic peers. Evidence suggests (see Further Reading section below) that one major reason is that South Asian women are restricted from moving about their communities without their husbands or other family members. In India there is a further quirk to the data: women are simultaneously becoming more educated and less likely to work. Apparently, in the face of limited employment opportunities, they are pursuing degrees to make themselves better marriage material.

The obstacles keeping women from work have such deep cultural roots that they may appear unmovable. But if you look back to the graph, Bangladesh is much closer to that U-shaped line. EPoD directors Rohini Pande and Charity Troyer Moore attribute this to growth in the country’s garment industry and argue that, “Seemingly immutable norms can crumble when labor markets begin to value women’s work.”