Visiting Economic Historian Maggie Jones on links between development economics and economic history in North America

EGC Affiliate Spotlight: Maggie Jones

Twentieth-century guides for Black travelers and twenty-first century surveys of Indigenous youth in Canada may initially seem like disparate historical resources, separated by form, demographic subject, place and time. But for economic historian and EGC visiting scholar Maggie Jones, these documents are keys to understanding the effects of institutions on the ability of marginalized people to thrive in North America.

Originally from Canada, Jones sees her work as “research on development within developed countries”, using a variety of archival and survey resources in her wide-ranging, socially impactful research. She came to EGC as an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Victoria and will leave after this semester to join the department of economics at Emory University in Atlanta. Aside from continuing to work on her research endeavors, during her time at Yale she has organized the weekly economic history seminar and several conferences in economic history, including, Diversity and Ideas and Resilience in History. She is currently teaching an undergraduate survey course in American Economic History and will be organizing a conference related to race in economic history in the Spring of 2022.

Access to education for Indigenous youth in Canada

Originally intent on studying architecture, Jones came to the study of economic development in graduate school “on a whim”, but quickly became interested in the influence of economics upon education, health outcomes, culture, and beliefs. Since then, she has pursued a range of projects pertaining to the intersection of economic history and economic development in North America.

“In Canada, Indigenous people are often said to get post-secondary education for free, which is false,” she said. Since her time as a graduate student, she has conducted extensive research on the impacts of the residential school system, treaties between Indigenous peoples and white colonists, and the relationship between student financial aid and educational attainment.

She finds that these historical interactions with the Canadian government have significant relevance to Indigenous peoples’ economic situation in modern-day Canada. For example, the treaties initially made with Indigenous people “promised educational attainment”, an agreement which has led, in varied forms, to some funding for secondary education. But with changes to educational standards over time, the “attainment” acknowledged in the treaties has grown outdated. “What you need to participate in the labor market today means something different than it did in the late 1800s,” she said.

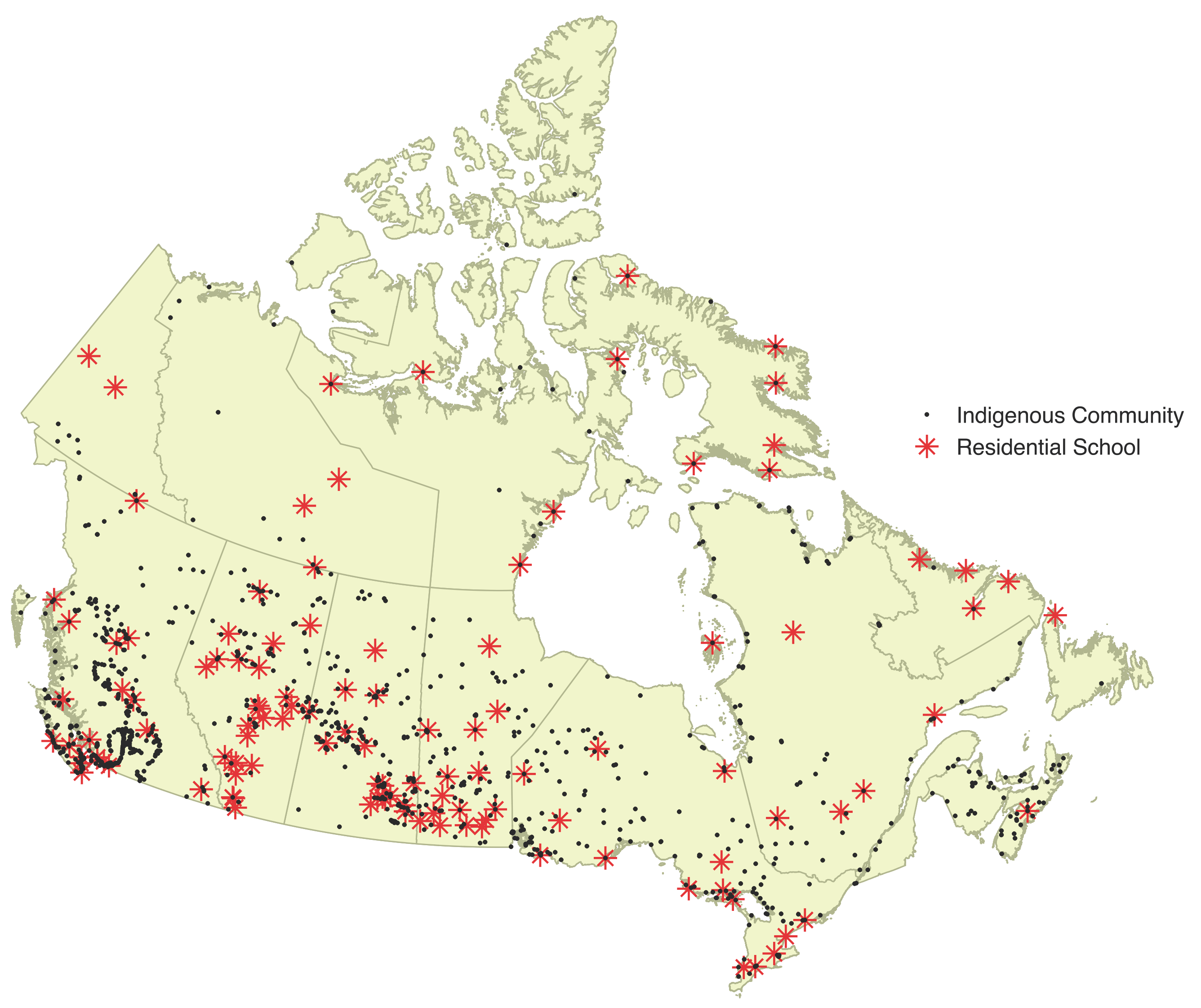

Jones researched the history of education and Indigenous peoples in Canada, focusing on the residential school system, a network of boarding schools funded by the Canadian Department of Indigenous Affairs and administered by a variety of Christian organizations. From 1894 to well into the twentieth century, the system forcibly enrolled Indigenous children with the aim of assimilating them into white Canadian culture. Abuse at these sites is well documented, and has recently come to international attention due to the exposure of mass graves at several former residential schools.

Map showing locations of Indigenous communities and residential schools, courtesy Maggie Jones.

“Often people know about [residential schools] from books or the newspaper”, says Jones, “but the more you learn about educational attainment, and treaties, and the interconnectedness of it all, the more you realize that you can’t study educational attainment at it pertains to Indigenous populations without thinking about the legacy of residential schools.”

Jones looked at a restricted government database, which contained responses from Indigenous people in Canada concerning their family history with residential schools, as well as their responses to a variety of socio-economic questions. While previous research suggested residential schools increased the human capital (educational attainment and other benefits) of attendees at great expense in other dimensions, Jones found that whatever human capital was gained was not transmitted intergenerationally.

Jones points to the disruption in ties to family and culture, as attendees of residential schools were less likely to speak an Indigenous language and engage in traditional activities, and more likely to live far from traditional communities. This trauma disrupted the transmission of human capital from parent to child, contrary to previous economic scholarship studying the transmission of human capital in other contexts.

Jones’ findings do, however, offer an optimistic perspective on the future of descendants of residential school attendees. Her conclusions relate to the concept of “Indigenous resilience”, which incorporates “individual, social, political and cultural dimensions of adjustment” (Masten 2001). Jones’ evidence empirically demonstrates that access to Indigenous cultural centers can mitigate the negative effects of intergenerational trauma from the schools.

Developing Research About the Green Books

Researching post-secondary funding for Indigenous students led Jones to read about educational grants for American veterans, and especially about the differential impacts of GI Bill funding on Black and white beneficiaries. This funding project was extremely successful in terms of educational attainment for white students, but segregation and discrimination in academic institutions prevented Black students from taking advantage of the resources.

This line of research led Jones to her current project, which broadly considers the economic impact of segregation on Black people through the metric of travel and accommodation, using twentieth-century travel guides as her primary resource.

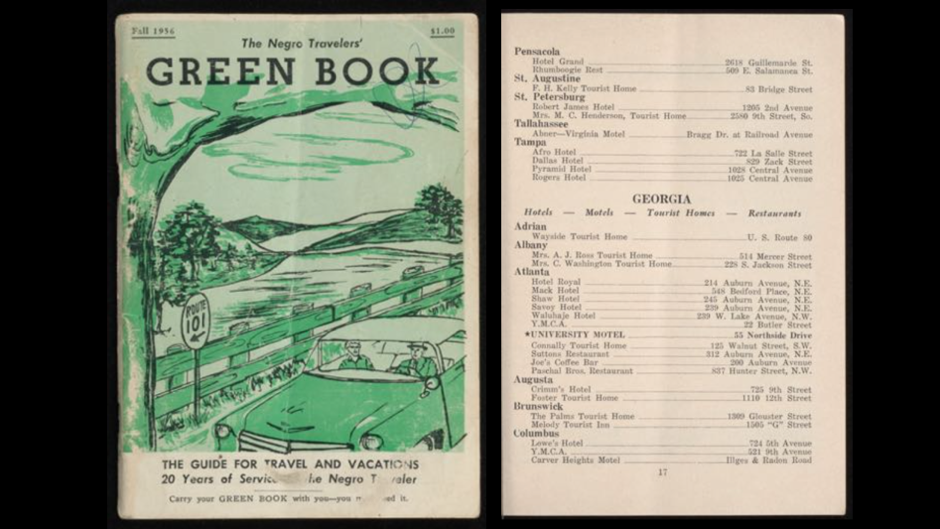

In the years between 1936 and 1966, Black travelers throughout North America kept a copy of the Green Book in their glove compartments. This annual motorist’s guide, originally authored by Victor Hugo Green, facilitated safe Black travel through Jim Crow America by documenting hotels, gas stations and restaurants that would serve Black people, as well as dangerous locations such as sundown towns.

1956 Green Book cover and listings in Florida and Georgia. Images courtesy Maggie Jones.

In a paper accepted at The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Jones and her co-authors Lisa D. Cook, Trevon D. Logan, and David Rosé use the data provided by the Green Books on the number of non-discriminatory opportunities available by region, and analyze the factors influencing counties with a greater proportion of these accommodations. Their paper then examines whether establishment owners upheld segregation in order to appease discriminatory white consumers. In doing so, they suggest that federal legislation was necessary to end these discriminatory practices.

The project has led to a heightened awareness of Green Books as an academic resource, and to the increased digitization and improved access of these important documents. At the EGC, Jones has continued her research into the Green Books, looking at both the geography of segregation in accommodations, as well as the economics behind segregated travel, including the cost of segregation to Black consumers; and the influence of anti-segregation legislation on accommodation, travel, and the economy.

Jones focuses her research on economic history in North America, yet sees parallels with her EGC colleagues, development economists studying the Global South. “I think that a lot of issues that are really pertinent to development economics are the same issues that are pertinent to thinking about economic development on reservations or reserves,” she said.

Written by Clare Kemmerer