Sagar Saxena on the economic effects of India’s agricultural support policies

India boasts large and long-running government-sponsored programs to support its agricultural markets. These programs have been in place since the 1960s and 70s and impact hundreds of millions of people directly since agriculture is the primary source of income for nearly half of the country’s workforce. Three of the most important programs which aim to support both farmers and households are: fertilizer subsidies, wholesale crop procurement at attractive pre-announced prices, and the sale of subsidized grains to low-income households. While there is extensive work on the scope and nature of the individual programs, little is known about their combined economic effects on producers and consumers.

To address this gap, new research by Sagar Saxena, a postdoctoral associate at the Economic Growth Center (EGC), and coauthor Shresth Garg examines how these three agricultural intervention programs interact with each other and assesses their overall impacts on farmers and households. Using a structural model of supply and demand in India’s agricultural sector, they find that consumers – especially lower-income consumers – and large farmers benefit from these programs, while smaller farmers are unaffected, if not slightly harmed.

For Saxena, who began his economics career in the policy-oriented field of industrial organization (IO), the paper’s combination of large government datasets with intricate models of individual farmers’ decision-making processes underscored the potential of using IO tools to pursue development economics research.

Photo by Vestal McIntyre.

Photo by Vestal McIntyre.

From industrial organization to development economics

Originally from Uttar Pradesh, one of India’s poorest states, Saxena was always interested in how governance and public policy affects people’s lives. This translated into a wide range of academic interests, including history, political science and international relations. While studying in Geneva, Switzerland, to pursue these interests, however, conversations with professors shifted his interest towards economics, which he hoped could help “settle [the] debates” about policy questions that he had long puzzled over through other disciplines.

After completing his undergraduate studies, Saxena worked in economic consulting. Working on topics related to antitrust and competition exposed him to IO, a policy-oriented field in economics that often uses large datasets with theoretical models of firm and consumer behavior – which led him to begin a PhD program in IO at Harvard.

But during the second year of his PhD program, Saxena took a course in development economics – a field in which he initially had little interest. Here, he was exposed to a suite of interesting theoretical models of firm and household behavior in developing countries but found that the related empirical work only tested some of the main predictions of these models in field experiments. This slight disconnect between theory and empirical work, he realized, was a methodological ‘niche’ for himself: given his training in IO, he could more closely align theory and empirics, and potentially use these empirical models to simulate "policy experiments" to answer questions that could not be answered through field experiments alone. He quickly imagined a wide range of applications and policy areas that could be pursued through such an approach.

Looking back on how this course redirected his academic journey, Saxena offered a sentiment echoing the late economist Robert Lucas, “Once I started thinking about applications of IO tools for answering development-related questions, it was hard to think about anything else.” As he attended IO seminars, watching speakers present research typically focused on the US, Saxena's mind would wander to how these empirical models could be tailored for developing countries, imagining the untapped potential if only the right data were accessible.

With that in mind, in 2023, Saxena completed his PhD in IO with a fresh focus on development – and his recent paper, “Distributional Impacts of Indian Agricultural Interventions,” highlights the powerful potential of combining these methodological approaches.

Modeling India’s agricultural interventions

As noted, India has three key agricultural programs. In the first program, the government sells highly subsidized fertilizers to farmers. Under the second program, which also directly supports farmers, the government buys a substantial share of key crops like wheat and rice at attractive prices known as Minimum Support Prices (MSP). Finally, in the third program, the government sells these grains to households at heavily subsidized prices through a public distribution system (PDS). Together, the three programs cost about 1.2% of India’s GDP and impact nearly 800 million people.

"Once I started thinking about applications of IO tools for answering development-related questions, it was hard to think about anything else"

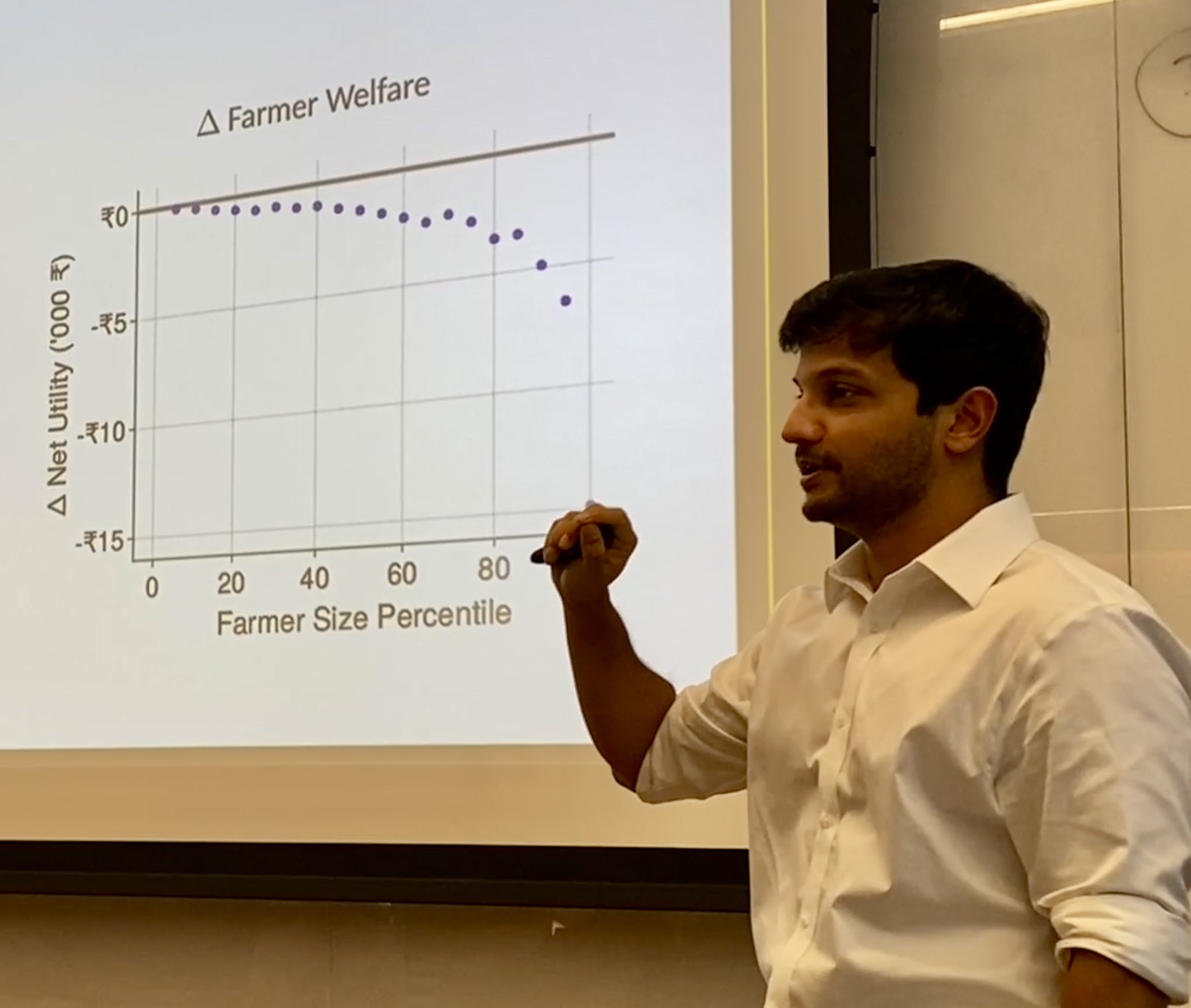

Utilizing a structural model of supply and demand and large datasets on these three Indian programs, Saxena and his coauthor were able to analyze how the programs interacted and assess their overall impacts on farmers and households. They found that the programs, when taken together, were beneficial to low-income consumers. In particular, they determined that the MSP procurement program reduced household food spending by 15-20%. Likewise, they observed that the programs benefit many farmers – but that these benefits are primarily enjoyed by large-scale farmers, who are more able to access the programs. They found that the MSP procurement program, for example, benefits the largest farmers while slightly harming small-scale producers who are less able to find and secure government buyers.

Many of these results reflected what economists call “equilibrium effects” – or economic effects that only become visible when implemented widely, such as through policy programs. By raising crop output through its fertilizer subsidies, for example, the government would have more crops to purchase from farmers through its MSP procurement program and more food products to sell to low-income households through its PDS program. This would decrease low-income households’ reliance on private agricultural markets, however, lowering prices and thus farmer revenues in those markets - and since, as noted, small-scale farmers have less access to MSP procurement, they are more exposed to this potential adverse effect.

To account for these equilibrium effects, Saxena and his coauthor’s model had to consider the decision-making processes of individual farmers and how those decisions affect the industry as a whole. For any given farmer, their model factors in their choice and share of which crops to plant, the level of fertilizer subsidy, the prices they expect to earn through MSP procurement, and the price they expect to earn in private markets. By aggregating these choices across the entire industry, the researchers could assess how the three programs interact with each other – and whether any inequalities or inefficiencies hindered their implementation.

For example, there are large differences in the geographic distribution of these programs. Some regions – like Saxena’s home state of Uttar Pradesh – see less than 5% of rice and wheat being sold to government buyers through the MSP program. Farmers in states like Chhattisgarh or Punjab, by contrast, sell 30-50% of their output through MSP procurement. While the reasons behind these regional dynamics need to be explored in greater depth, Saxena notes that they may stem from regional differences in the availability of government buyers and information about the program. This highlights a central challenge with MSP procurement, which has been a source of political tension in recent decades: large-scale farmers who know the program, have access to government buyers, and can transport their crops to government warehouses often reap the lion’s share of the program’s benefits.

The theoretical nature of their empirical model also allowed Saxena and his coauthor to play around with different program configurations. They were able to analyze, for example, how the overall effects would change if one or more programs were increased, decreased, or eliminated altogether. These findings have broad policy implications – which, as Saxena notes, ultimately depend on what the goals of the programs are.

“When these programs started in the 1960s, the objective was food security,” he said. “In recent years, the focus and rationale has been farmer welfare.”

Photo by Peter Zhang

Photo by Peter Zhang

Sagar Saxena presenting “Distributional Effects of Agricultural Interventions in India” at the Yale Development Workshop, organized by EGC, on February 19, 2024.

Expanding horizons about ‘structural’ development

As a postdoctoral associate at EGC, Saxena has used his time to wrap up a few significant projects, including a structural analysis of deregulation policies in India’s cement industry and an examination of the country’s industrial policy surrounding solar power. This fall, he will join the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania as an Assistant Professor.

A highlight of Saxena’s time at Yale was helping to organize EGC’s Firms, Trade, and Development Conference last October. Ahead of the conference, he and fellow organizer Rahul Shukla reviewed recent literature on policy interventions to address market frictions, a topic that dovetails closely with his recent paper.

“It was nice to see where the research was right now,” said Saxena about the conference. “Hearing [the expert] perspectives about where research should go with the findings we have now, that was helpful.”

Indeed, the conference coincided with the launch of EGC’s Markets and Development Initiative, which – much like Saxena’s broader research efforts – seeks to combine insights from the fields of development economics and IO, as well as international trade. This kind of alignment highlights what Saxena has appreciated most about his time at Yale.

“What’s amazing about Yale is that many people are open to interdisciplinary work, to combining models and data, to learning new methods and giving you feedback,” he said.

Written by Peter Zhang