Are There Too Many Farms in the World? New research on agricultural productivity in developing countries

Farm Scale and Productivity

Several studies have shown that the relationship between farm size and productivity differs in developing and developed countries. In low-income countries, where small farms are prevalent, larger farms appear to be less productive than the smallest farms, while in advanced economies, larger farms become more productive with scale.

A new study uses data from India to connect the dots between these two phenomena, showing that farm productivity follows a U-shaped curve with farm size, and that substantial gains in output and income would result if farms in developing countries were significantly larger. The analysis suggests that agricultural consolidation – though a challenging policy prospect – could lead to significant economic growth and poverty reduction.

Results at a Glance

- New data analysis shows a U-shaped relationship between farm productivity and farm scale, observed globally.

- The smallest farms, which dominate low-income countries, are more productive than slightly larger farms because of the costs of hiring additional labor.

- Larger farms have increasing productivity with size because they can take advantage of machines that have higher capacity and lower cost at larger scales.

- In India, the optimal farm size is estimated to be 24.5 acres – over 7 times today’s average size of under three acres – using technology available in India today.

- Increasing all farms in India to the optimal size would increase output per acre by 42% and output per worker by 68%. The redistribution would result in an 87% decrease in the number of farms, but a reduction in the total labor force of only 16%.

Explaining the U-curve in low-income countries using unique data

In low-income countries like India, Indonesia, China, Tanzania, and Colombia, agriculture is dominated by farms that are, on average, much smaller than those in more developed countries, where farming is typically on a large scale. The relationship between farm productivity and farm size also shows a global pattern: the smallest farms in low-income countries are more productive than farms that are slightly bigger (decreasing returns to scale, in technical terms), while in the developed world, productivity increases with scale.

While the inverse relationship between farm size and productivity in low-income countries is well-established, a new study by Mark Rosenzweig, the Frank Altschul Professor of International Economics and an EGC affiliate, and coauthor Andrew D. Foster of Brown University, shows that the U-shape relationship between scale and productivity that is observed across richer and poorer countries occurs within a single low-income country – that is, productivity falls as farm size increases from its smallest unit, and then rises as farm size increases, after a threshold. What has remained a puzzle until now is what drives this pattern: why is the relationship between farm scale and productivity U-shaped? Why are small farms more productive than those which are slightly bigger but far less productive than the larger farms observed in high-income countries?

The authors take advantage of unique data from an Indian panel survey, which uniquely contained a substantial fraction of larger farms, to show that this U-curve relationship is driven by two factors: the transaction costs of labor (i.e. the cost of hiring additional farm workers) and the scale-economies of machine capacities.

Explained in simple terms: on a very small farm, family members work the land, participate in wage work on other farms, and operate their farm efficiently. As farm size increases, the family members increase their level of on-farm work until they are unable to spend any more time working (this point of complete self-sufficiency is known as autarky). Because hiring additional labor comes with additional transaction costs (finding workers and travel costs) and thus lowers net income, the family continues to work the land as farm size increases (decreasing labor to land ratio, or productivity) until such point that the benefit of hiring additional workers outweighs the cost, and productivity starts to increase – which is where we observe the bottom of the curve. After this point, productivity rises with farm size, as larger farms can take advantage of machines that have higher capacity at larger scales and lower labor use – mirroring the economies of scale that are well-observed in developed countries.

Increasing farm size could expand agricultural output and reduce poverty

The discovery of this U-shaped pattern within a single context means that what researchers had previously understood about farming in low-income countries was wrong: that is, the smallest farms are not necessarily the most productive. In short, there are too many small farms – especially in low-income countries. The research implies that increasing farm size through consolidation would ultimately increase agricultural output, while substantially reducing poverty in agriculture. The authors illustrate this point using their model to show that the minimum farm size in India that would maximize return on land using only locally- available machinery is 24.5 acres – over 7 times the mean farm size in India today. If all farms were this size, the number of farms in India would decrease by 82%, total output would increase by 42% and income per farm worker would increase by 68%. However, there would only be a 16% decline in the total agricultural workforce, owing to the under-utilization of labor in most small-scale farms.

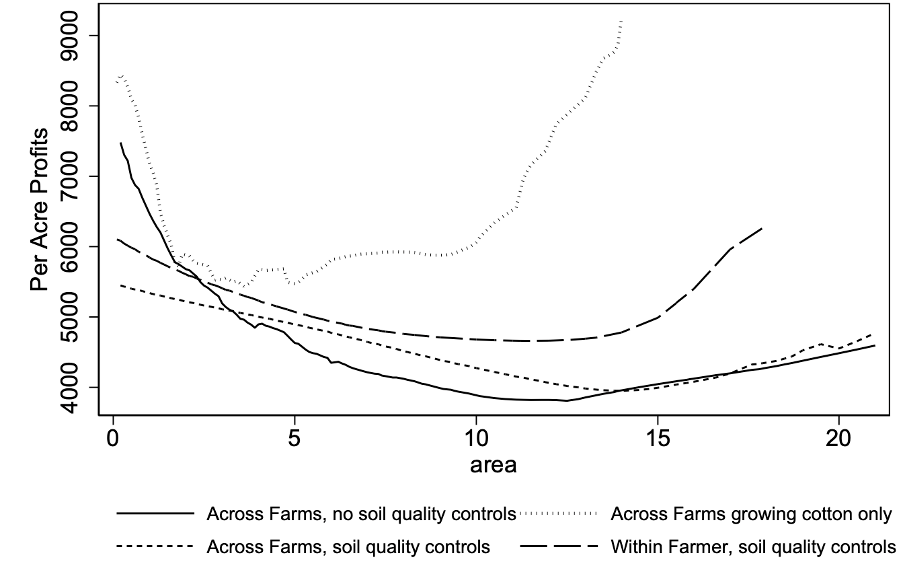

A graph from Foster and Rosenzweig (2021) showing real profits per acre by owned area in India, with the different lines taking into account differences in plot quality and farmer characteristics. Data come from the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) survey of India, 2009-14.

The authors call attention to the fact that their findings are consistent with a study the government of India made over 70 years ago. In 1947, the United Provinces Zamindari Commission concluded that there were too many small farms in India and that this had a negative effect on the country’s output and poverty levels. Today, however, India’s government is in support of the large number of small land-holdings, and as recently as last year, the Minister of Agriculture stated that while Indian farms are smaller than they have ever been, output is increasing so that there is no evidence that small scale farming is not a cause of the low level of agricultural productivity. Until now.

New findings on the effects of widespread arsenic poisoning in Bangladesh

EGC affiliate Mark Rosenzweig and coauthors combine economics, genetics, and family lineages to show the direct effects of arsenic-contaminated water on cognition, physical strength, and earnings.

Rosenzweig argues the government’s conclusion in 1947 is still true today. He stresses that part of the reason behind the consistent defence of small agriculture is that, historically, all the evidence from small farm countries suggested that increasing farm size would decrease productivity. “When you look at existing data, they show that the smallest farms are the most productive. There has been no evidence to refute this view – until now, when we get to see the U-shape because we have more data than before on the few larger farms that exist in India today.”

A challenge for global development

The research suggests that having too many small farms is a development bottleneck for the world and for large producers like India. Agriculture is the dominant economic activity in low-income countries, accounting for, on average, more than 25% of GDP and employing at least 40% of the total workforce. This new evidence thus presents a big idea for growth: it implies that increasing farm size through consolidation could substantially increase agricultural output while reducing poverty and agricultural employment. “If we want to understand barriers to growth, this shows that small farming is both a symptom and a cause of under-development,” Rosenzweig says.

While these findings are compelling for low-income countries, the authors argue that the likelihood that small-scale farmers would increase their landholdings to reach the optimal farm size, on their own, is remote. This is because of the initial decreasing returns to increasing farm size previously described, and the enormous level of coordination required by farmers to “leap the chasm” from a small to a much a larger farm when all neighboring farms are also small.

When asked for historical examples of how countries made this shift, Rosenzweig points to France. Following the Second World War, France enacted several major policy changes concerning agricultural land use. Starting with the establishment of INRA (the French Institute for Agricultural Research) in 1946 and extending through the establishment of Common Agricultural Policy by the EU in 1962, compulsory land consolidation in France was used to increase land productivity by lowering the costs of production. Initially enacted in response to the food shortages of the war, land consolidation offered an opportunity to modernize farming practices and to contribute affordable food for the nation and for trade across Europe. Land consolidation is ongoing in Europe and encompassed 38 million agricultural hectares (one quarter of all cultivated land) as of 2004.

Rosenzweig suggests that his study provides evidence that economists and governments have been thinking incorrectly about small-scale farming in recent decades, and that technologies and processes that augment output on a small scale, emphasized by many NGO’s, are unlikely to make big shifts in agricultural productivity. Small farms are likely to remain the dominant form of production in low-income countries for the foreseeable future, but a policy shift favoring agricultural consolidation, though a challenging prospect, could lead to significant poverty reduction.

Research Summary by Emma Lambert-Porter. Infographic designed by Goodness Okoro.