New findings on the interplay of insurance, agricultural inputs, and crop yields for poor farmers in India

The equilibrium impact of agricultural risk on intermediate inputs and aggregate productivity

Floods, droughts, and other extreme weather events are major sources of risk for smallholder farmers, often destroying their harvests and leaving them with little to no income for the season. In semiarid regions of India, roughly nine in ten farming households cited drought as the largest risk to their harvest. In response to this risk, farmers underinvest in fertilizer to save money or plant low-risk, low-yield crops instead of more profitable ones. This underinvestment in farming inputs can lead to large-scale macroeconomic impacts on a country’s productivity.

In a recent paper, Kevin Donovan, Assistant Professor of Economics at Yale School of Management and an EGC affiliate, explores the nationwide economic impacts of providing crop insurance to smallholder farmers in India. His results show that implementing crop insurance would increase farmers’ investment in fertilizer and boost overall crop yields, growing India’s overall agricultural productivity. Further, Donovan’s results suggest that adopting the use of improved seeds could have broader economic effects than previously researched, such as reducing inequality between farmers.

In Donovan’s model of the Indian economy, providing all farmers with crop insurance would increase agricultural productivity by 16%

Providing all farmers with crop insurance is projected to reduce the U.S.-Indian agricultural labor productivity gap by 14%

There are additional gains to risk-mitigating measures like improved seeds when rolled out nationwide that do not appear in the smaller-scale randomized controlled trials, increasing agricultural productivity by 6% and GDP per worker by 5%.

Implementing a large-scale policy to provide farmers with improved seeds is projected to reduce the misallocation of farming resources and ultimately reduce inequality between rich and poor farmers.

Every harvest season, poor farmers in developing countries face the risk of bad weather destroying their crops. While crop insurance or other technological advances like risk-reducing seeds could offer protection against this risk, most poor farmers in developing countries don't have access to crop insurance. As a result, they have to make a difficult decision every harvest season: should they spend their scarce financial resources on fertilizer, which could increase crop yield, or forego buying needed fertilizer in case bad weather destroys the crops and save resources to feed their household? Most farmers are forced to save some money, instead of spending it on the optimal amount of fertilizer, to ensure they have leftover savings to feed their family in the case a storm strikes. The downside, though, is that this lack of investment in fertilizer lowers the yield of a farmer’s harvest.

People are willing to forgo some profit from their farms to reduce exposure to potential shocks and consumption”

- Kevin Donovan

Altogether, this underinvestment in fertilizer due to uninsurance can have profound macroeconomic implications given that the least developed countries in the world employ 70% of their population in the agricultural sector. Indeed, poor countries lag behind rich countries in the efficiency of their agricultural sectors: In the United States, fertilizer expenditures make up 40% of all harvest revenue, but in India, that number falls to 11%.

One potential cause for poor countries’ low agricultural productivity is the inefficient use of intermediate inputs like fertilizer by smallholder farmers due to a lack of insurance. In his paper, Donovan primarily explores this connection between insurance and intermediate input intensity (i.e. how much farmers invest in fertilizer), quantifying their impact on the broader economy.

Modeling the uncertainty farmers face

Donovan’s model simulates the Indian economy’s agricultural sector, in which farmers combine inputs (e.g. seeds, labor, fertilizer) to produce their outputs (e.g. harvested crops). In the past, small-scale randomized controlled trials have quantified the positive effects of farmers insurance and improved seeds. Yet, the question left unanswered is what happens when you give all poor farmers access to insurance or improved seeds? By modeling for random weather events, lack of insurance, and farmers’ food constraints, Donovan provides an accurate simulation of farmers' decision making in the face of uncertainty, revealing the large-scale impacts that come with risk-mitigating measures for farmers.

Results and Policy Lessons:

Crop insurance increases a country’s agricultural productivity.

A key finding from Donovan’s model is that providing smallholder farmers with crop insurance is projected to increase India’s total agricultural productivity by 16%. Risk makes farmers, especially poorer ones, scale back the amount of inputs like fertilizer they use. Evidently, Donovan found that most, about 64%, of this productivity increase was explained by farmers’ increased willingness to invest in fertilizer once they have access to crop insurance. The other 36% was explained by the fact that poorer farmers are more likely to receive farming resources they need in well-insured markets.

Crop insurances also decreases the productivity gap between rich and poor countries.

There are large differences in agricultural productivity between low-income nations like India and high-income countries like the United States. Donovan simulated the introduction of agricultural insurance into the U.S. and Indian economies, and found this agricultural productivity gap declined by 14%. Overall, these results indicate that insurance can significantly reduce the disparity in output across low-income and high-income nations.

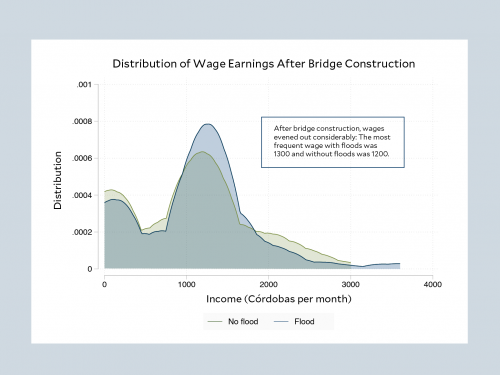

Bridges between villages in Nicaragua serve as links to markets

EGC researcher Kevin Donovan and coauthor find that building footbridges positively affects rural economies in flood-prone areas.

There may be additional gains to risk-mitigating policies when rolled out nationwide that do not appear in the smaller-scale randomized controlled trials.

Rich farmers often use large amounts of fertilizer because in the event of a weather disaster, they will still have enough money to cover their day-to-day living needs. Poor farmers don’t have this luxury, leading them to invest small amounts of fertilizer for fear of not having enough money left to feed themselves or their families in the event of a storm or drought. But improved seeds have the potential to reduce this investment inequality. Previous research has found that improved, more durable seeds mitigate the risk of losing crops to bad weather. These seeds prompt farmers to invest more in fertilizer and high-yield farming activities, increasing their overall harvest output.

Donovan’s model reaffirmed this effect. However, Donovan’s simulation revealed other positive price effects that previous randomized controlled trials had not considered. As millions of Indian farmers implement improved seeds and grow their crop yields, his model found that the price of crops falls, making it easier for everyone — including the farmers themselves — to purchase food. With the more affordable prices of food, it is easier for poor farmers to feed their families, further reducing the risk farmers often face when confronting the possibility of poor weather conditions. They can properly invest in their fertilizer knowing they can easily feed their families if disaster strikes their harvest. Altogether, when accounting for this price effect, Donovan found that improved seeds increased agricultural productivity by 6% and GDP per worker by 5%.

Further, Donovan found this price effect reduces inequality between rich and poor farmers. For rich farmers, who were not previously concerned about the tradeoff between feeding their families and fertilizing their farms, the drop in crop prices lowers the value of their harvest. In turn, rich farmers reduce the amount of fertilizer they use. This excess material is then redistributed through market forces to poorer farmers. Ultimately, when implemented at scale, this improved seed program is projected to reduce inequality of farming inputs (fertilizers) and income between poor and rich farmers.

If you scale one of these programs, the gains are much larger than if you just replicated the results from one study,”

- Kevin Donovan

Mushfiq Mobarak, a Professor of Economics at Yale and an EGC affiliate, put the paper’s contribution in a different light. “Donovan’s paper tackles two of the most important, classical questions in the field of economic growth: Why are there such large productivity differences across countries? And more specifically, Why are productivity differences so much larger in the agriculture sector than the non-agricultural sector?”

Mobarak explained that the paper offers an elegant theory that can explain these facts: agricultural productivity is particularly low in poor countries because the high degree of risk faced by farm operators (e.g., from weather) acts as a major deterrent to investment in intermediate inputs like fertilizer. When efficiency is low, farm operators choose to use fewer intermediates to limit their exposure to bad shocks, which happen to be more costly when agents are closer to their subsistence requirements. When efficiency is low, farmers, especially poorer ones, choose to use fewer intermediates to limit their exposure to bad shocks, which happen to be more costly when agents are closer to their subsistence requirements

“Donovan explores the aggregate, economy-wide consequences of this, which is a nice complement to other micro papers that have used experiments with farmers to document the low investment in fertilizer in the face of risk,” Mobarak said. “This is the strength of the diversity of research approaches across faculty affiliated with EGC. Taken together, it provides more holistic understanding of development issues”

Implications for agricultural policy

The impact of crop insurance for smallholder farmers in poor countries makes intuitive sense: without the existential fear of weather shocks destroying their harvest, low-income farmers can make more optimal farming decisions. Donovan’s study fills a key gap in the literature by modeling the aggregate impacts that such factors can have on a country’s broader economy. The findings indicate that crop insurance and other risk mitigation strategies can have a significant impact on low-income countries’ agricultural productivity, narrowing the productivity gap between rich and poor countries and reducing inequality between farmers.

As policymakers in India and other developing countries strive to grow their economies and lift poor farmers out of poverty, these results show that lack of access to risk mitigation tools like crop insurance and improved seeds can have large potential benefits.

As noted by Donovan, “When we think about broad economic policy, we generally think of policy at the level of a state or country. Accurate policy debates must understand the effects that occur at scale.”

Research Summary by Diego Haro