“Brain drain” or “brain gain”? New research identifies a more nuanced story about skilled migration

Many educated and skilled citizens from low-income countries continue to emigrate to high-income countries. As global education levels rise, international competition for talent intensifies, and many destination countries adopt immigration policies that favor high-skill migrants, the outflow of high-skill migrants from low-income countries is likely to continue. This trend has raised concerns that such high emigration rates may result in substantial losses of human capital for countries of origin – a phenomenon colloquially referred to as “brain drain.”

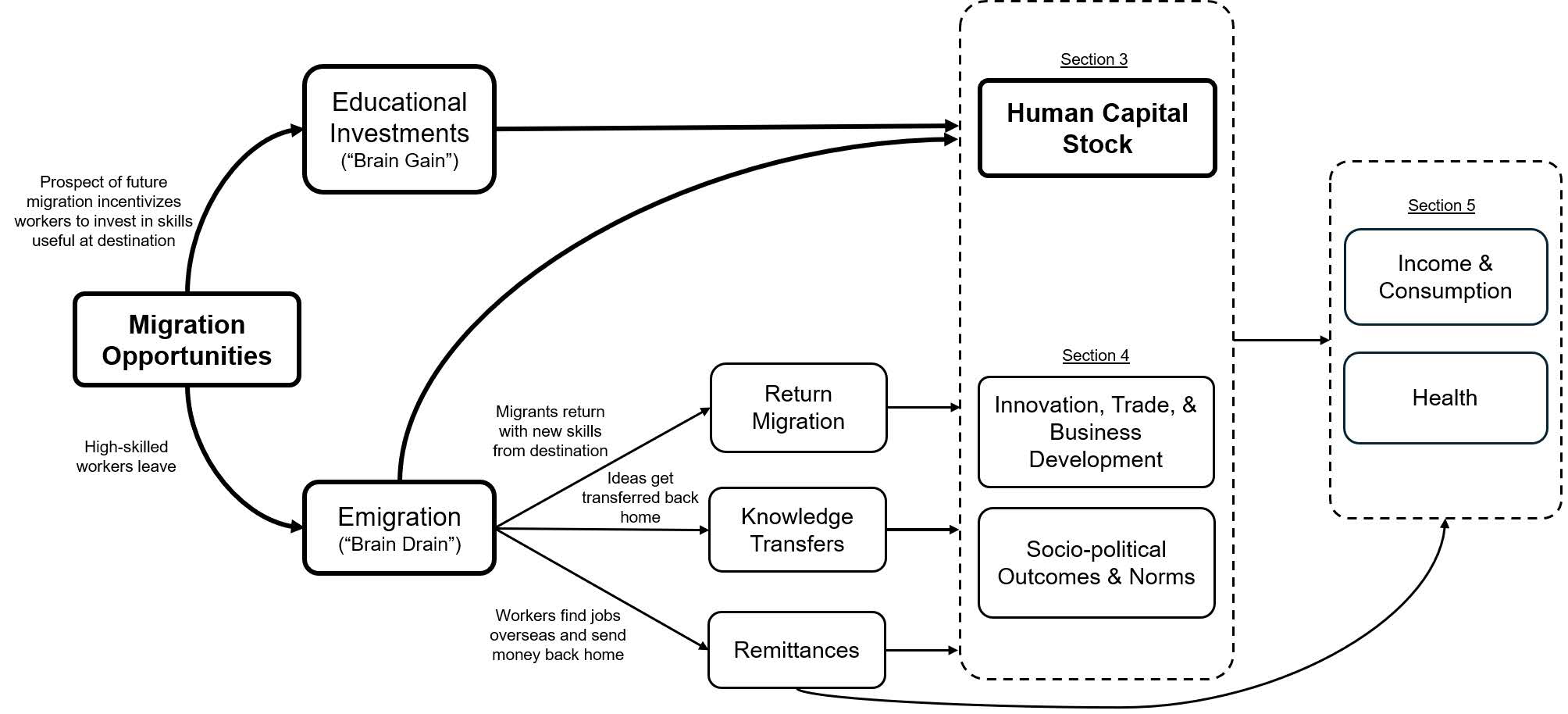

But in a new Science article, EGC affiliate Mushfiq Mobarak and coauthors review papers that apply modern causal identification empirical methods to analyze the effects of emigration in greater detail. Notably, they identified causal channels through which emigration can actually lead to increased human capital and welfare in origin countries – a process dubbed “brain gain.” Their findings paint a more nuanced picture of emigration, which the authors hope can motivate more informed policies in origin countries.

Wage benefits from migration and visa policies in destination countries incentivize investment in specialized education, thereby increasing the human capital stock in origin countries.

Migrants send remittances that help finance local education and businesses, while diaspora networks open new channels for trade and investment, boosting local innovation, entrepreneurship, and knowledge exchange.

Whether emigration leads to brain drain or brain gain is shaped by local capacity and policies, particularly the ability of education systems to produce new skilled graduates and the extent to which business and trade conditions support the reintegration of returnees.

Framework containing direct and indirect channels of migration (Batista et al. Science)

Brain gain through human capital advances

The typical story of brain drain is that the emigration of high-skilled workers depletes human capital stock in origin countries. However, Mobarak and coauthors highlight growing evidence showing that new migration opportunities – such as expanded foreign visa programs for healthcare and technology workers – can actually increase the stock of high-skilled workers. For example, coauthor Caroline Theoharides from Amherst College has shown that the introduction of a new U.S. visa program for nurses led to large increases in investment in nursing training in the Philippines, such that it ultimately led to an increase in the number of domestic nurses within the Philippines, since many newly licensed nurses were not ultimately able to move abroad. Similarly, another coauthor Gaurav Khanna from UC San Diego has shown that relaxing the strict cap on H-1B visas – a U.S. work permit that lets companies hire foreign workers for specialized jobs requiring a college degree or higher – prompted many Indian students and workers to acquire computer engineering skills, spurring the establishment of new specialized colleges to meet this demand. In short, when migration pathways open or expand, individuals invest in the skills aligned with foreign labor demand, which can lead to more skilled workers at home.

Additionally, Mobarak and his coauthors found that even lower-skilled migrants experience significant earnings gains from working abroad. For instance, Bangladeshi migrants who won a Malaysian work lottery tripled their income relative to others who were unlucky and did not win the visa lottery. The remittances almost doubled the income of their households back home. Other research shows that as migrants send remittances home, these funds can be invested in education over time, paving the way for more high-skilled migration in the future and ultimately boosting income and educational attainment in the origin country.

Importantly, the researchers emphasize that substantial brain gain can only occur if the origin country possesses adequate training infrastructure to develop skilled labor. To achieve this, policymakers must ensure that institutions can expand the supply of specialized training programs, focusing on vocations and skill sets that align with labor market demands both at home and abroad.

“You could have the brain drain effect, unless your country figures out how to produce skilled workers” says Mobarak. “Whether we get brain drain or gain on net depends on that.”

Networks, norms, and business innovation gains

The researchers also identified several gains from migration related to business, innovation, and entrepreneurship. As migrants establish diaspora networks abroad, they help attract foreign investment and create links to international markets. Likewise, for migrants who return home, the knowledge and skills gained abroad can be put to use domestically, boosting knowledge transfer. For example, Chinese returnees with foreign management experience were found to increase the valuation and productivity of the firms they joined upon return. Similarly, returnee employees at a large Indian company filed more U.S. patents. Returning migrants can also bring home business ideas developed abroad and establish new firms that rely on local workers.

The effects of migration in origin countries can also extend to less tangible domains. For instance, migrants and diaspora networks can transmit ideas about political and social norms, including those that promote gender equity in their home countries. In the Bangladesh-Malaysia example highlighted above, there were significant improvements in women’s decision-making power within households when their husband won the Malaysian visa lottery. Such changes in gender norms can generate broader benefits, including improved child health and development outcomes, as well as delayed marriage and childbirth.

For policymakers: Adaptation, rather than prevention

The income boosts experienced by migrants lead to better living standards for their family members (through remittances), and these income shocks can improve local development in the origin country, from increased educational investment to downstream benefits like fertility and family planning. Moreover, these findings offer some reassurance against concerns that emigration of healthcare workers undermines health outcomes in origin countries; indeed, migration can lead to an overall brain gain in the domestic healthcare sector.

Whether migration ultimately leads to brain drain or brain gain depends crucially on which types of workers are in demand within destination countries, as well as on the capacity of the origin countries’ training institutes to produce new skilled graduates in those fields. Since this capacity is shaped by government policy, it is something that policymakers can – and should – focus on.

Mobarak hopes that this research can help governments view brain drain as part of a much broader and more complex migration story, one that also includes important indirect effects and potential spillover benefits.

“The risk of brain drain exists, but now, this framework allows us to unpack the elements of that risk,” he says. “Rather than saying ‘brain drain is a problem, so we should discourage migration,’ the question for governments is: 'how do we ensure that migration maximizes the chances of a win-win-win scenario for the source country, the destination country, and the migrant’s family?'’”

Johannes Haushofer (Cornell), David McKenzie (World Bank), Daniel Han (Boston University), Catia Batista (NOVA Lisbon), and Dean Yang (Michigan) are the other coauthors of this review paper published in Science.

Research Summary by Peter Zhang.