New research on why authoritarian regimes have local leadership elections

The Rise and Fall of Local Elections in China

A trade-off between autocratic control and local information can explain institutional choices in dictatorships, according to new research coauthored by Gerard Padró i Miquel, Yale Professor of Economics and Political Science and an EGC affiliate.

When a state is poor and has little resources, it cannot afford to monitor a large, dispersed population of local officials. This is where local elections become important. The autocrat delegates monitoring of local elected officials to the citizens who, via elections, can use their local knowledge to better select and to discipline these officials. The downside of this arrangement is that elected officials have weak incentives to implement unpopular policies mandated by the central government. Hence, as the state becomes richer, the autocrat is likely to undermine local officials and take back direct control.

The study tests this logic with a large new dataset that documents change in the political economies of more than 200 Chinese villages over 40 years.

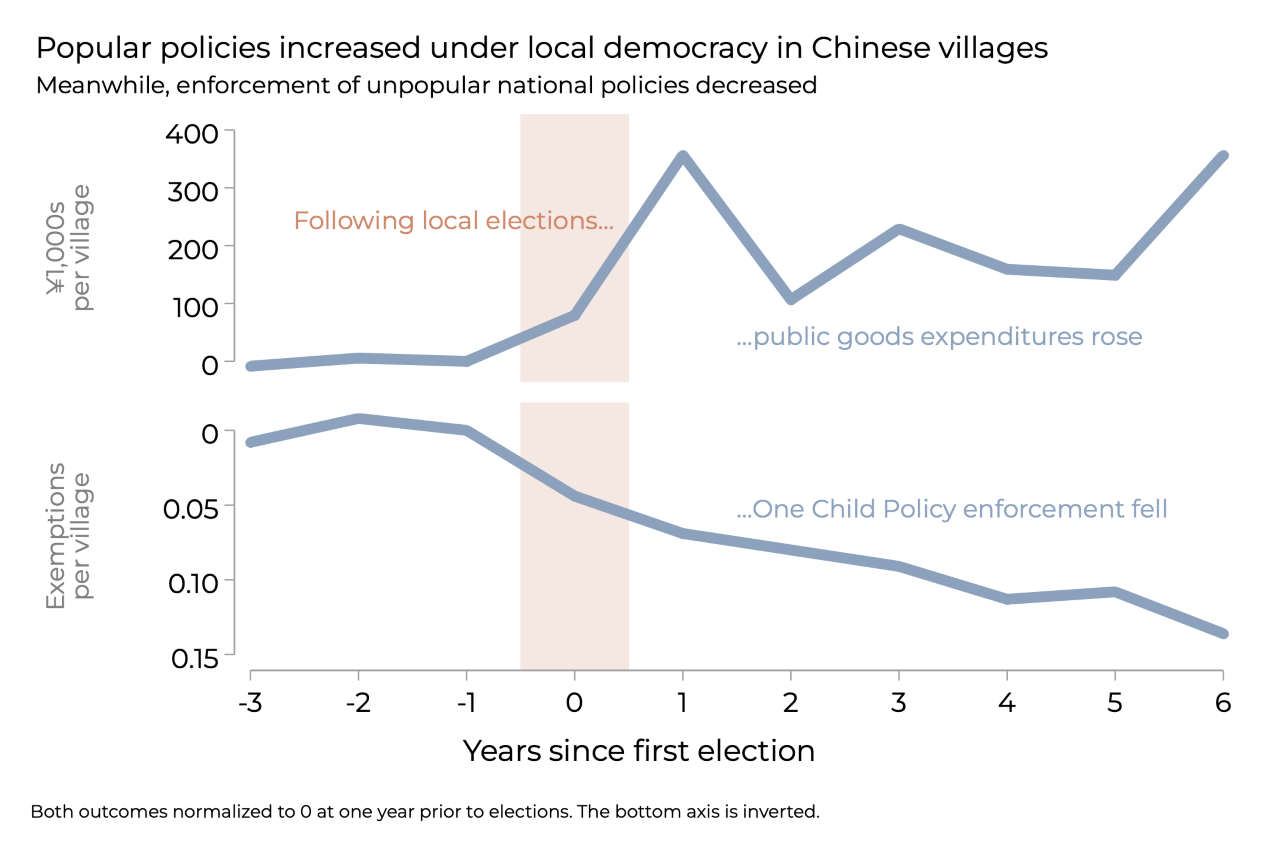

The research finds that the benefits in terms of better monitoring indeed come with a loss of direct control for the autocrat. Local officials care about their re-election outcomes, so while they exert effort to implement popular policies, they are reluctant to institute unpopular policies. This undermines autocratic power. The study shows that as bureaucratic capacity increases, the power of elected officials is undermined as the vertically controlled bureaucracy reasserts dominance.

When China had little resources in the 1980s, they used local elections as a low-cost way to monitor the population.

Citizens held their local official accountable which led to a lowering in corruption and responsibility shirking.

A local official’s re-election incentives also lead to less implementation of unpopular central policies.

As China’s economy grew, the central government increased support towards county governments who strengthen direct control over villages, thus undermining the role of elected officials.

Bureaucratic capacity was an important part of China’s re-centralization.

Many autocratic governments allow both national and local elections. Pakistan under Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Indonesia under General Suharto, and China in the 1980s and 1990s are all examples of autocratic governments that introduced locally elected bodies designated to deal with administrative matters. While the issue of national elections in autocratic countries has been explored in economic literature (typically interpreted as a means of distributing spoils among the elite) the phenomenon of local elections has been under-explored – beyond speculations that they imply political transformation from autocracy to democracy.

“During China’s extraordinary economic transformation in the 1980s and 1990s, many social scientists thought something extraordinary was also happening in the political domain,” Padró i Miquel said in an EGC interview. “But local elections were not a ‘new dawn for democracy’ in China. The politburo simply identified a problem – corruption and bad governance in rural parts of the country – and determined that local elections would solve that problem while maintaining the central government’s tight political control.”

Since few economic studies have explored such dynamics, Padró i Miquel and co-authors Monica Martinez-Bravo, Nancy Qian, and Yang Yao sought to fill this gap in the literature by studying local elections in China. In a paper published this month in the American Economic Review, they demonstrate that in situations where the autocrat has a lack of resources, local elections help them maintain control.

A new public dataset on China

China presents an informative case study to researchers interested in these questions, as it is a large, stable autocracy with a highly heterogeneous population. The researchers track this introduction and progression of Chinese local elections to explore how means of control evolve alongside a country’s economic progress.

In the 1980s, Chinese officials were struggling with a weak control of the countryside. This led to corruption, shirking, and a lack of public goods. The Chinese central government did not have the resources to improve information collection. They therefore delegated control over local officials to informed villagers. These elections started in the early 1980s but were codified by the central government in the 1987 Organizational Law on Village Committees (OLVC). Village committee members were elected with the position of Village Chairman going to the candidate who received the greatest number of votes. Beginning in 2002, when the Chinese government could afford more vertical control due to economic growth, the government began eroding the power of these village governments.

To analyze these dynamics over time, the researchers built a unique dataset, carefully documenting the political economy of Chinese villages over years. The researchers work with a large dataset documenting 200 Chinese villages over 40 years. The dataset originates from the annual National Fixed Point Surveys (NFS) conducted by the Ministry of Agriculture. Villages were regularly sampled to reflect China’s rural population focusing on households’ economic and agricultural production.

“The data is like looking at a window into the past,” Padró i Miquel observed. “It shows that people in rural regions had an unfavorable view of local government in the early 1980s, but those views improved after local elections were introduced – especially with the relatively impressionable demographic of young people aged 18 to 25, who increasingly saw governments doing what they were supposed to do and being more accountable to citizens.”

The researchers created their own Village Democracy Survey (VDS). This was added to the NFS. The VDS focused more on the political economy and elections, collecting disaggregated data instead of focusing on village-level aggregate data. The VDS was collected in 2006, 2011 and 2019. The first survey wave recorded a variety of political and financial variables and the second wave recorded the names of local officials from 1982 to 2005. Finally, the third wave attempted to study the loss of autonomy of local officials.

Political Distortions and Economic Development

Held in conjunction with the 31st Kuznets Lecture, the Kuznets Mini-Conference on Political Distortions and Economic Development highlighted current work on themes relevant to the Kuznets lecture. Gerard Padró i Miquel spoke on a panel on “Research and Research Directions in Political Distortions and Economic Development” alongside Rohini Pande and Leonard Wantchekon.

A trade-off between monitoring and direct control

The lack of implementation of unpopular central policies poses an issue to the autocrat. Autocratic leaders often struggle with maintaining control to implement their policies across an entire society. “Dictators sitting in capitals are trying to control rural villages,” Padró i Miquel explained. In large countries like China, villages are often culturally and even linguistically diverse and therefore are difficult to monitor continuously. Introducing local elections meant that candidates were often well-known by their peers and active members of the village community. This greatly improved the corruption and shirking. “If the villagers have a choice, they won’t pick the guy who is corrupt,” Padró i Miquel explained.

The findings demonstrate that election incentives and increased local accountability leads to an increased implementation of popular policies and a reluctant implementation of unpopular policies. Those who implement popular policies are more likely to be re-elected. The researchers use public goods expenditure and land availability to households as examples of popular policies at the time. Officials who provided more public good expenditure were elected at a higher rate. Further, the findings show that elections were followed by increased public expenditure to address electoral promises.

Conversely, the framework demonstrates that Village Chairmen who instituted unpopular state-mandated policies were re-elected at a lower rate. For example, the One Child Policy, which attempted to limit Chinese families to one child each, caused wide-spread discontentment. The researchers found that the Village Chairmen likely helped their villagers to circumvent it, undermining the control of the central government. Similarly, policies to expropriate village land for infrastructure projects like roads or airports were also extremely unpopular; the study found that Village Chairmen were also less compliant with its implementation. Since Village Chairmen had been elected by their constituents rather than appointed by the state, their selective lack of compliance risked lower consequences.

The researchers argue that China’s dramatically increased fiscal capacity led to an undermining of village autonomy starting in 2003. Between 1980 and 2015, China’s per capita GDP increased from about $740 to over $8,000 and government revenues increased by more than twenty times. Throughout the 2000s, the government began to undermine VCs as well as invest in information collection systems that would notify them if local officials deviated from central policies. County governments that were in place to supervise villages began to visit more often and take more managerial and fiscal control. This was first codified in the 2003 Tax and Fee Reform, which prohibited village governments from raising their own revenues by setting their own fees. County governments further instituted more managerial practices including the cadre-in-residence program, in which county officials spent multiple days a week in a village. As counties increased revenues, they gained more vertical control.

Interestingly, the researchers also found that distance from county capitals mattered. Consistent with the logic, the more remote a village was, the more likely they were to retain their autonomy.

The organizational framework provided by the paper demonstrates that there is a trade-off in delegation due to divergent interests between citizens and the autocrat. Improved performance thus comes jointly with weaker autocrat control. When the autocrat becomes richer, therefore, they are more likely to invest in vertical structures. This helps explain China’s policies surrounding VCs post 2002. However, the researchers emphasize that there were other forces driving recentralization, including shifting priorities and changes in party leadership.

Looking forward

This research explains why autocrats introduce local elections as a means of monitoring instead of a move towards democracy or more political openness. Local elections are cheap alternatives to vastly improving the means of vertical control.

The researchers note that these insights can be applied to countries beyond China. For instance, General Suharto’s regime in Indonesia saw a similar phenomenon of decentralization and recentralization, and similar cases can be found throughout recent history across the globe – offering rich potential for further research.

Research Summary by Anusha Sarathy. Infographic by Nils Enevoldsen. Banner image: An 400 yuan postage stamp from 1954 shows a Woman Worker Voting in the First National Congress.