Towards Gender Equality Newsletter Issue #8: Understanding Fertility Decline

A significant takeaway from the past century of rapid fertility decline around the world is that decisions about how many children to have do not occur in a vacuum. Parents pay attention to health signals such as children's survival prospects. They pay attention to the time and costs of raising children, as well as the benefits they bring to the household, such as their ability to work on a family farm or their long term earning prospects in a given economic environment.

Parents pay attention to what others are doing in terms of educational investments and extra-curricular activities to ensure that their children can compete with their peers. Some may pay attention to how many girls and boys they have based on how different genders are regarded and rewarded in a society.

Parents also consider their own health, time, and aspirations, and the support (or penalties) they can expect from partners, families, societies and governments.

Often, this rich set of internal calculations is reduced to simplistic caricatures in the public discourse. We hope that this newsletter opens up a whole world of compelling research on the agency and welfare of individuals today, and how investments in the future are shaped by the current economic and social environment.

Aishwarya Lakshmi Ratan

EGC Deputy Director

Research Highlight

Long-run Impacts of Forced Labor Migration on Fertility Behaviors: Evidence from Colonial West Africa

Dupas, Falezan, Mabeu, Rossi [Working Paper]

Fertility rates in sub-Saharan Africa remain among the highest in the world, with a slower decline than in other regions. While some scholars attribute this to deep-rooted cultural preferences for large families, Mabeu and coauthors’ research investigates the role of long-term economic disruptions rooted in colonial labor policies. Using a unique historical natural experiment in Burkina Faso, the authors investigate whether the forced migration of young men in Burkina Faso under French colonial rule has shaped fertility behavior across generations.

Insight 1: Historical exposure to forced labor migration predicts lower fertility today

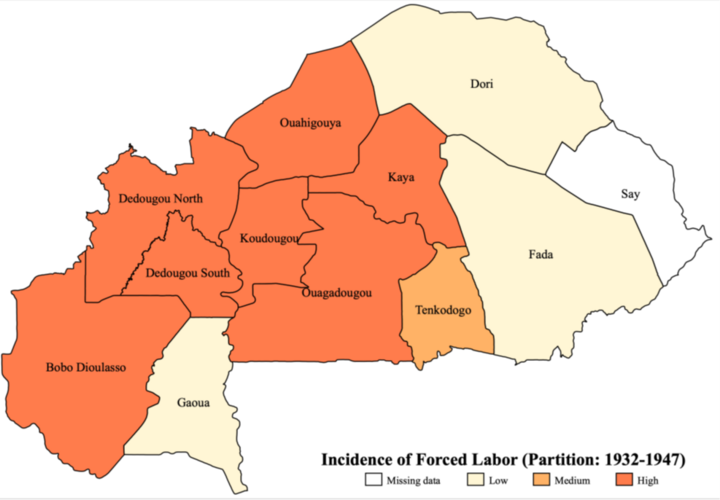

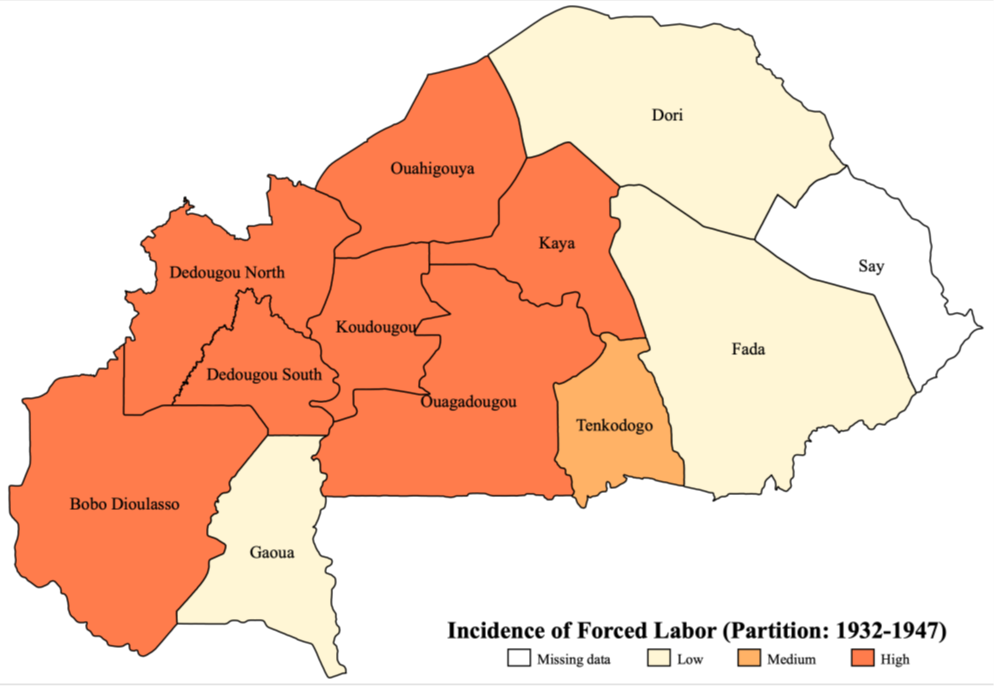

Between the 1910s and 1940s, tens of thousands of young men in Burkina Faso were conscripted to work in infrastructure and plantation projects in neighboring colonies, especially Côte d’Ivoire. As shown in Figure 1, the southern and western regions of present-day Burkina Faso, were heavily targeted, while eastern regions —annexed to Niger during the 1932 colonial partition and lacking similar labor demand—were largely spared.

Figure 1: Heterogeneity in historical exposure to forced labor migration within present-day Burkina Faso

Note: This map shows variation in recruitment intensity across Burkina Faso based on archival records. Darker colors indicate higher rates of conscription.

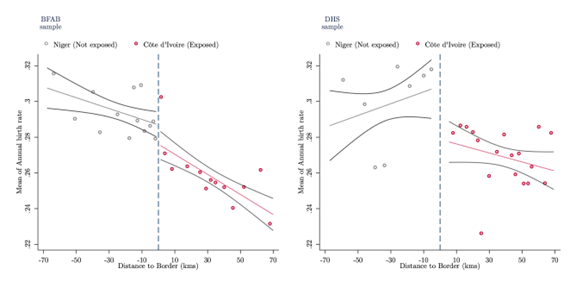

Exploiting this spatial variation in colonial recruitment intensity, the authors show that villages with higher historical exposure to forced labor migration exhibit significantly lower fertility today—by about 0.5 fewer children per woman by the end of reproductive age. This is shown in Figure 2 using two different geo-referenced contemporary datasets: data from the Burkina Families Aspirations and Behaviors project (BFAB) and Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS).

Figure 2: Effect of colonial forced labor migration on annual birth rate

Source: BFAB (left) and DHS (right). The figure plots the average annual birth rate (y-axis) against the distance to the Côte d'Ivoire-Niger boundary (x-axis). The analysis is restricted to observations within our main bandwidth (70 km). The vertical dashed line marks the boundary separating areas exposed to forced labor migration (Côte d'Ivoire in pink) from areas not exposed (Niger in light grey). Villages are grouped in equal-sized bins on each side of the boundary and each bin is represented by a dot. The lines overlaid on the dots represent the best linear fit and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals on each side of the boundary.

Insight 2: Persistent circular migration and inflow of remittances are the key transmission channels

To explain this long-run negative effect on fertility, the paper shows that colonial labor policies established migration corridors that persisted across generations. Even after independence and the end of formal coercion, temporary male migration to Côte d’Ivoire remained concentrated in the same areas historically targeted by colonial recruiters. These flows have become self-sustaining, fueled by private employer demand (particularly cocoa plantations) and entrenched networks. Households in historically exposed regions are more likely to send male migrants to Côte d’Ivoire and receive regular remittances, highlighting a powerful channel of persistence rooted in colonial-era economic geography.

Insight 3: Migration and remittances altered household labor needs and optimal family size

The study shows that remittance inflows have led to modest economic diversification. Adults in exposed villages are more likely to engage in non-agricultural activities, and children spend less time on farm work. Household heads also report lower demand for family labor, weakening the economic rationale for large families. The result is a shift toward smaller optimal family size, even though measures of women's education, empowerment, or child mortality remain largely unchanged. This suggests that remittances drove fertility decline by shifting production away from subsistence farming, not by improving human capital.

Insight 4: Structural transformation—not cultural change—is key to understanding fertility decline

The study concludes that smaller family sizes are not only a reflection of changing norms but also a response to economic restructuring. This challenges the idea that fertility behaviors in Africa are purely shaped by fixed cultural norms. The study also highlights a "reversal of fortune": areas once targeted for their labor potential remain locked into low-return migration patterns, with only modest gains in economic development. Yet, even without major improvements in capital accumulation, the shift away from family farming has significantly changed reproductive choices. This underscores the importance of viewing fertility through the lens of economic transformation and historical context, not just social norms.

Featured Researcher: Marie Christelle Mabeu

Marie Christelle Mabeu is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at Toronto Metropolitan University and an invited researcher at the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). She holds a PhD in Economics from the University of Ottawa, and her research lies at the intersection of applied microeconomics, development economics, family economics, and political economy.

Marie Christelle Mabeu

In a recent working paper, Mabeu and co-authors ask whether decades of forced labor migration dating back to colonial times shaped fertility behaviors in West Africa, analyzing the case of Burkina Faso (see Research Highlight above). In another co-authored working paper,Mabeu exploited the discontinuity in institutions across the British-French colonial borders to find that women in former British areas are more likely to delay sexual debut and marriage and have fewer children. They find that the impact of colonial origin on fertility is “partly driven by differences in the timing of colonial population policies” and their effect on the use of modern contraceptive methods.

See Mabeu’s website for more information.

“Fertility behaviors are deeply shaped by historical institutions and migration patterns, yet their long-run consequences for gender inequality and economic outcomes remain underexplored. My research focuses on understanding how structural forces—such as colonial labor policies or population planning regimes—have shaped fertility preferences and behaviors over time. This lens helps uncover how past policies continue to influence women’s choices, labor market participation, and the broader trajectory of gender equity in low- and middle-income countries today.”

- Marie Christelle Mabeu

New Research

Babies and the Macroeconomy

Goldin [Working Paper]

Fertility levels have greatly decreased in virtually every nation in the world, but the timing of the decline has differed even among developed countries. In Europe, Asia, and North America, total fertility rates of some nations dipped below the magic replacement figure of 2.1 as early as the 1970s. But in other nations, fertility rates remained substantial until the 1990s but plummeted subsequently. This paper addresses why some countries in Europe and Asia with moderate fertility levels in the 1980s, have become the “lowest-low” nations today (total fertility rates of less than 1.3), whereas those that decreased earlier have not. Also addressed is why the crossover point for the two groups of nations was around the 1980s and 1990s. An important factor that distinguishes the two groups is their economic growth in the 1960s and 1970s. Countries with “lowest low” fertility rates today experienced rapid growth in GNP per capita after a long period of stagnation or decline. They were catapulted into modernity, but the beliefs, values, and traditions of their citizens changed more slowly. Thus, swift economic change may lead to both generational and gendered conflicts that result in a rapid decrease in the total fertility rate.

Did the Modern Mortgage Set the Stage for the U.S. Baby Boom?

Dettling & Kearney [Working Paper]

This paper proposes that the adoption of the modern U.S. mortgage (i.e., low down payment, long-term, and fixed-rate)—led by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Veteran’s Administration (VA) loan insurance programs—set the stage for the mid-twentieth century U.S. baby boom by dramatically raising rates of home ownership for young families. Using newly digitized data on FHA- and VA- backed loan issuance and births by state-year, and a novel instrumental variables strategy that isolates supply-side variation in loan issuance, the authors find that the FHA and VA mortgage insurance programs led to 3 million additional births from 1935-1957, roughly 10 percent of the excess births in the baby boom. Aggregate effects mask differences by group—the authors find no effects of FHA/VA lending on births for Nonwhite women, consistent with well-documented racial discrimination in these lending programs. These results highlight the importance of access to home ownership for fertility decisions.

Firstborn Daughters and Family Structure in Sub-Saharan Africa

Genicot & Hernandez-de-Benito [Working Paper]

Does the absence of missing baby girls in sub-Saharan Africa imply a lack of son preference in the region? This paper uncovers systematic gendered effects on family structure and fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Using data from Demographic and Health Surveys, the authors show that having a firstborn daughter, rather than a son, significantly influences women’s family dynamics. Women with a female firstborn experience higher long-term marriage rates but are less likely to marry the child’s father when the birth occurs prior to formal union. They also face higher divorce rates and greater likelihood of entering polygamous unions. Despite these marital transitions, they tend to have more children. Their analysis further reveals that having a firstborn daughter is associated with poorer living standards and adverse health outcomes for mothers. To examine the mechanisms driving these patterns, the authors employ a geographic regression discontinuity design along ancestral ethnic borders separating matrilineal and patrilineal traditions. This approach highlights patrilineality as a key driver, shaping both marriage dynamics and fertility.

Parental Leave Policies, Fertility, and Labor Supply

Kim, Yum [Working Paper]

South Korea has been facing persistently low fertility rates and large gender gaps in labor supply. In response, the government has expanded parental leave benefits to address these challenges. To evaluate the effectiveness of these policies, the authors develop a quantitative, heterogeneous-household life-cycle model in which couples make joint decisions on careers, labor supply, savings, and child-related choices, including fertility, childcare, and parental leave take-up. The model is calibrated to recent Korean cohorts to replicate key patterns observed in the data, including segmented labor markets where career-oriented jobs require high entry costs and long working hours. The authors find that generous benefits increase fertility and reduce gender gaps in labor supply and wages by enabling more women to remain in career-oriented jobs during their child's early years, facilitating career advancement later. The positive labor supply effects are particularly strong among highly educated parents, and the policy can be self-financing through higher lifetime labor supply. Finally, the authors find that incentivizing joint parental leave use is more effective than mandating it and that the positive fertility effects may weaken when parents place greater emphasis on child quality—a trend observed in recent years. (See related published paper by Kim et al. (2024) titled "Status Externalities in Education and Low Birth Rates in Korea")

The Impact of Fertility Relaxation on the Gender Wage Gap

Agarwal, Li, Qin, Wu, Yan [Working Paper]

In this paper, the authors study the immediate impact of fertility relaxation on the gender wage gap. They explore a 2013 policy shock that relaxed the One-Child Policy in China. Using an employer-employee matched administrative data, this paper shows that after the policy shock, the salary of female new hires is reduced by 2.7% relative to the salary of male new hires, equivalent to a 47% increase in the gender wage gap in the data. The effect is more pronounced for female new hires aged below 35, implying the salary reduction is related to concerns about the increasing fertility of females.

The Negligible Effect of Free Contraception on Fertility: Experimental Evidence from Burkina Faso

Dupas, Jayachandran, Lleras-Muney, Rossi [Working Paper]

The authors conducted a randomized trial among 14,545 households in rural Burkina Faso to test the oft-cited hypothesis that limited access to contraception is an important driver of high fertility rates in West Africa. The authors do not find support for this hypothesis. Women who were given free access to modern contraception for three years did not have lower birth rates; even modest effects are rejected. The authors cross-randomized additional interventions to address inefficiencies that might depress demand for free contraception, specifically misperceptions about the child mortality rate and social norms. Free contraception did not significantly influence fertility even in combination with these interventions.

Policy Engagement, Events & Media Coverage

Rohini Pande in Science Magazine: "On the Economic Costs of Ending DEI"

EGC Director Professor Rohini Pande delves into research on meritocratic recruitment and talent allocation, and how US companies and universities can react to new legislation eliminating DEI activities.

Forthcoming Event: Harnessing Human Capital for Growth and Development in Kenya

The Yale Economic Growth Center (EGC) and Inclusion Economics at Yale University (YIE) will convene a research and policy dialogue in Nairobi, Kenya on June 30, 2025, in which we will discuss how macroeconomic transformation and growth strategies interact with gender gaps in sub-Saharan Africa, how investing in early childhood development can boost human capital and women’s socioeconomic advancement, how time use data can be effectively leveraged to inform policymaking, and how we can boost the digital economy through equal participation.

North East Universities Gender Day

On April 3, 2025 Yale Economic Growth Center and Yale Inclusion Economics launched the first North East Universities Gender and Development (NEUGD) Conference, bringing together early-career and senior scholars from universities in the northeast United States to explore the role of gender in the economy. The day-long conference featured twelve presentations by PhD students, covering topics ranging from gender disparities in the labor market and the home to the impact of abortion bans on maternal and infant health.

Designing Quality Care: Insights on Advancing Child Development and Women’s Empowerment

[Event Page; Conference Program & Speaker Bios; Professor Costas Meghir on the economics of early childhood development]

On May 7, 2025, the Yale Economic Growth Center and Yale Inclusion Economics, in collaboration with the MacMillan Center Council on African Studies at Yale University and the Gates Foundation, hosted a research-policy dialogue at Yale University highlighting emerging insights from a project examining the impacts of enriching public preschool quality and expanding access to younger children on children's and mothers' outcomes. This event brought together research-policy partners from the County Government of Tharaka Nithi in Kenya, the State Department for Gender and Affirmative Action in Kenya, and an interdisciplinary team of researchers from Yale University, Kenyatta University, Bangor University, and the University of the West Indies.

Additional News and Opportunities

Spotlight: Costas Meghir on the Economics of Early Childhood Development

In this EGC research spotlight, Yale EGC faculty affiliate Professor Costas Meghir discusses the economics of early childhood development, and how children can reach their full developmental potential through cost-effective and scalable programs.

Inclusion Economics Team Secures Funding to Expand Research-Policy Work for More Inclusive Digital Transformation

Yale Inclusion Economics researchers were recently awarded $3.5 million by the Gates Foundation in a new investment that will expand the evidence base on pathways to promote women as agents in the digital economy and encourage evidence-based programming.

Yale Researchers Offer New Insight into the Role of Women in Economic Development

Almost fifty years after the U.N.’s establishment of International Women’s Day, Rohini Pande, Pinelopi (Penny) Koujianou Goldberg, and other Yale researchers offer valuable perspectives on gender, structural transformation, entrepreneurship, technology access, childcare, and new analytic methodologies.

World Bank and Partners Release Two Calls for Proposals on Women and Jobs

The World Bank and partners have released two calls for proposals on Women and Jobs. The first, focused on Africa, has been released in partnership with African Center for Economic Transformation (ACET), the University of Ghana-Legon. It is a competitive call for papers and participation with a submission deadline of June 30, 2025, in advance of a policy research workshop planned for November 11-12, 2025 on the campus of the University of Ghana-Legon. The second, focused on Latin America and the Caribbean, is in partnership with Universidad de los Andes, Colombia, in collaboration with the Latin America and the Caribbean Gender Innovation Lab (LACGIL) of the World Bank, and the World Bank's Center for Research on Women and Jobs (CRWJ). It is also a competitive call for papers with a submission deadline of June 15, 2025, in advance of a workshop planned for October 6-7, 2025, to be hold in Bogota.