How an Early Vision of Training Global Economists Led to Yale’s International and Development Economics (IDE) Master’s Program

Yale economist Robert Triffin’s expansive vision and the Ford Foundation’s post-World War II priorities helped shape IDE’s unique approach to training development economists.

by Adena Spingarn

When Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin joined Yale’s economics department in 1951 – after a decade at institutions including the Federal Reserve, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the European Payments Union (which he helped found) – he was determined to address what he and many colleagues saw as a global shortage of well-trained economists in the post-World War II period. As attention turned to rebuilding national economies, Triffin believed that universities had a central role to play in this effort.

With Yale’s support, Triffin started building a master’s program to equip staff in government offices and international organizations with the practical tools needed to foster global economic growth. What is now the Yale International and Development Economics (IDE) master’s program began training its first international economists in 1952, received initial Ford Foundation funding in 1955, and helped lay the groundwork for establishing the Yale Economic Growth Center.

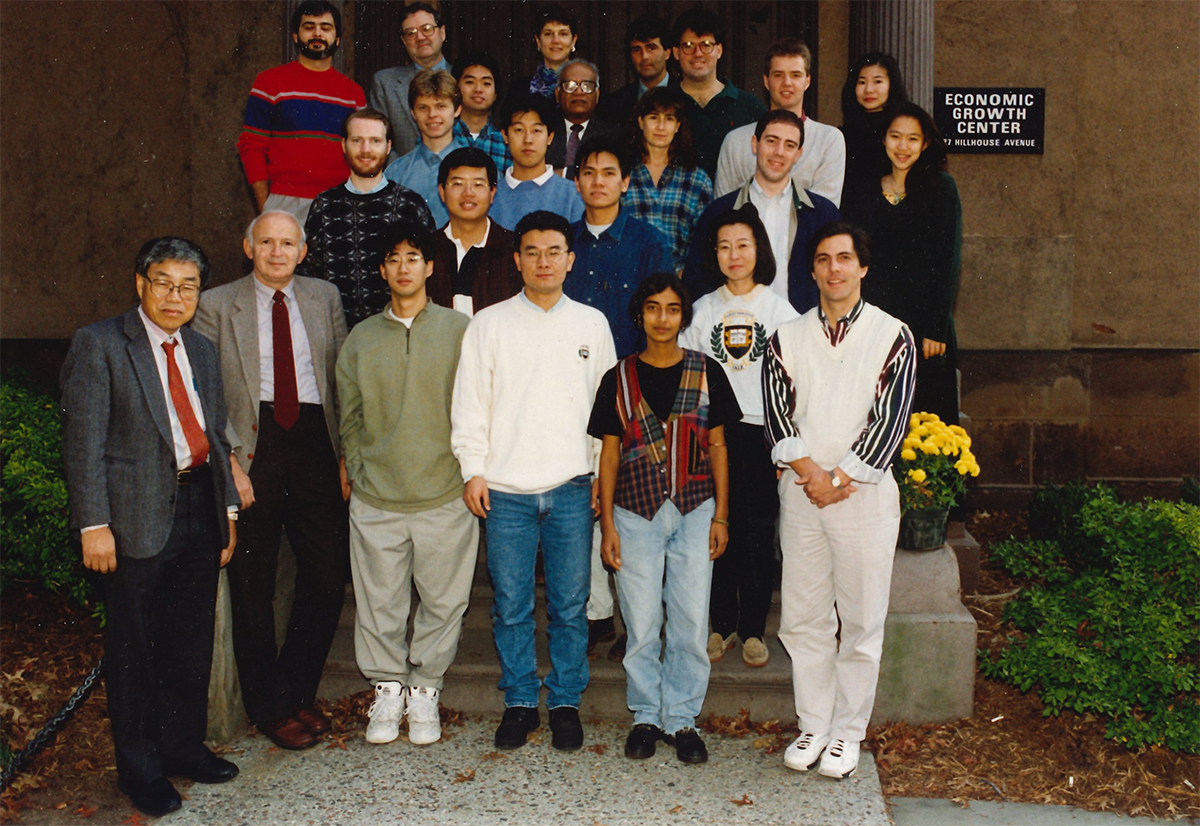

The IDE class of 1993 poses on the steps of Yale's Economic Growth Center.

A bold vision for training global economists

Shortly after arriving in New Haven, Triffin submitted a proposal to the Ford Foundation to create a foreign policy research and training program at Yale, with a special emphasis on international development. His vision, the proposed “Yale Center for International Administration,” aimed to train government and international organization staff to analyze economic data and produce research that would inform effective development programs and policies.

“There was a great need for economics practitioners who were not going to be academics, but at the same time had more than just an undergraduate level of education,” said IDE faculty co-director and Director of Graduate Studies Michael Boozer, who began leading IDE in 2002. “Triffin’s idea was that it was going to be helpful not just to the countries whose students came to study in IFEA, but to the policy economists in the United States as well, if practitioners around the globe had similar types of training, and contextual knowledge could be shared.”

“That original view proved prescient,” said Ana Cecilia Fieler, who became IDE faculty codirector in 2023. “Many IDE alumni went on to hold influential leadership positions around the world.”

Triffin proposed that the Yale center be “broadly patterned upon the [Harvard] Graduate School of Public Administration, but directed toward the international and foreign field rather than toward domestic government agencies in Washington.” The center would draw on an interdisciplinary advisory board including faculty from the law school and political science department, and would examine development challenges within a broad economic, political, and sociological context. In this way, it would fill the intellectual space recently vacated by the Yale School of International Studies, which closed due to a conflict with new Yale president A. Whitney Griswold. (That program was reestablished at Princeton as part of what is now the School of Public and International Affairs.)

In Triffin’s view, most graduate economics programs at the time focused on training future professors, not practitioners equipped to rebuild national economies or promote international cooperation. As he asserted in a funding proposal to Ford: “Economic research and training, in our graduate schools, still remain primarily oriented toward the preparation of teachers for other American colleges and universities. Most foreign students who come here under fellowship programs are fitted into existing curricula, even though few of them are destined to a teaching career upon return to their countries.”

Early progress & a revised proposal

Yale didn’t wait for Ford’s response to begin implementing Triffin’s ideas. In 1952, the university launched what became the Program in International and Foreign Economic Administration (IFEA) within the economics department, offering training for both Americans planning to work abroad and foreigners planning to return to their home countries. (The name stuck until 1977, when Yale economics professor Robert Evenson renamed it the Program in International and Development Economics – IDE – to reflect its broadened offerings. Evenson was director of the program from 1977 until 2002, during which time he taught and mentored hundreds of IDE students.) The initial curriculum emphasized the practical applications of economic techniques and policies to international development, with courses in economic theory, statistics, international economics, monetary policy, and economic planning.

A 1952 article in the Yale Daily News described the master’s program as “designed to train badly needed economic specialists” for institutions like the United Nations (UN) and the US government’s Economic Cooperation Association, an agency overseeing the Marshall Plan’s economic aid to Western Europe. Nominations from such institutions as well as foreign central banks produced IFEA’s first trainees. Initially, about half came from Europe – likely because their home institutions had to cover travel and living expenses. At the time, Yale hoped that the Ford Foundation or another private donor would help expand the program by sharing the financial cost.

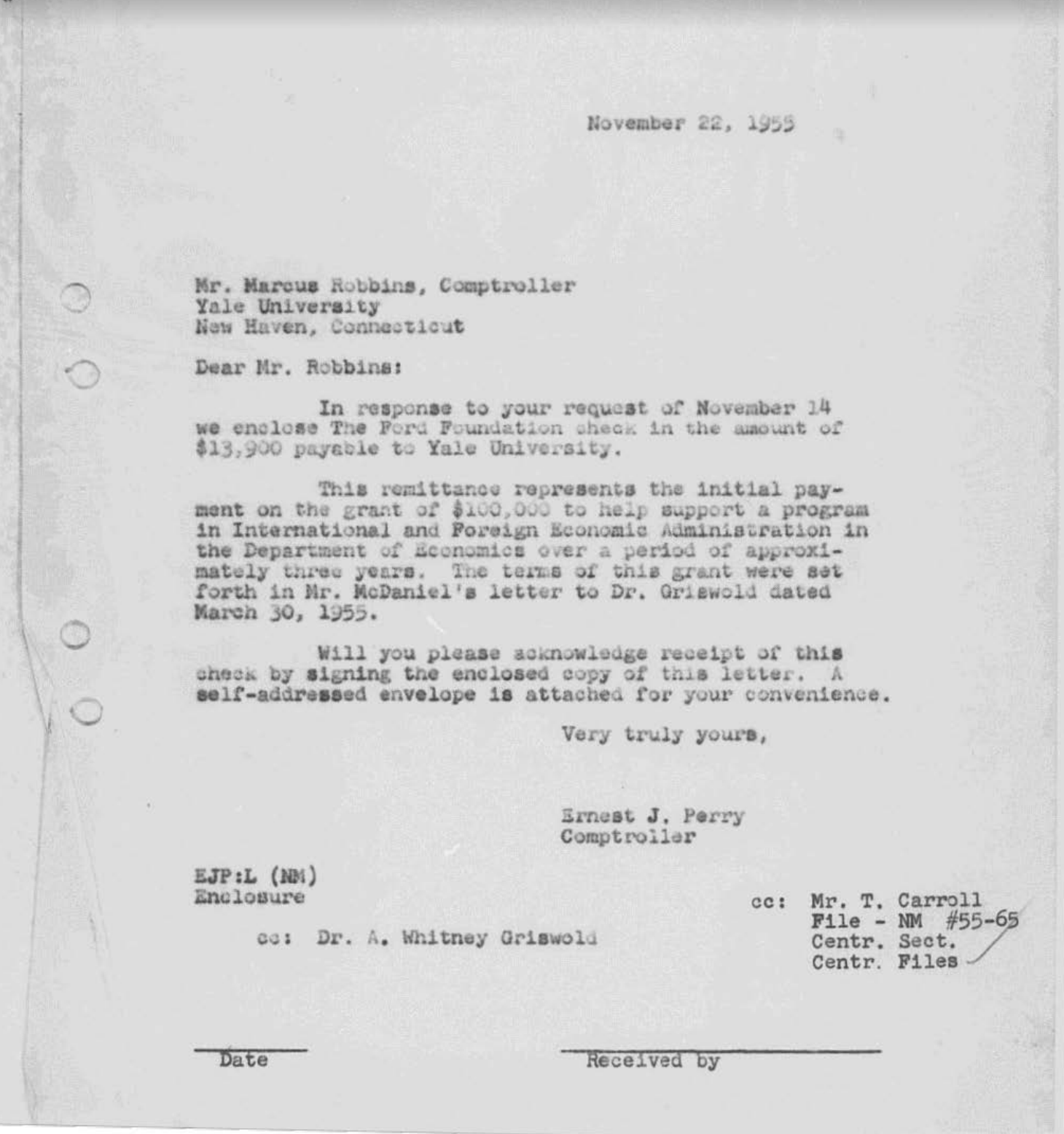

Unfortunately, some disappointing news arrived in 1954: the Ford Foundation declined to support Triffin’s initial proposal, arguing that it needed to play more to Yale’s strengths in economics and address the most urgent global development needs.

After Triffin revised the proposal, however, Ford awarded a three-year, $100,000 grant to expand IFEA, supporting more foreign students, visiting scholars, speakers, and research assistants, as well as building a more robust library of statistical documents. A five-year, $250,000 renewal followed in 1958. The program continued to grow in size and diversity, attracting more trainees from Africa and Asia, and from a wider range of economic institutions, including development agencies, treasury departments, statistical offices, and planning boards.

Despite its growth, the program maintained Triffin’s original emphasis on small class sizes, enabling close faculty attention and strong relationships between students.

The official invoice announcing funding from the Ford Foundation.

The birth of EGC

As IFEA grew during the late 1950s, training approximately 150 development economists in its first decade, economists including Lloyd Reynolds and Simon Kuznets began advocating for a dedicated research and training center that could help produce the kind of reliable foreign economic data that is so essential for informed economic policymaking.

In 1959, Yale developed a funding proposal to address this need through a new entity that would eventually become the Economic Growth Center (EGC). Central to this vision would be training economists to meet global development’s practical challenges – a goal that overlapped considerably with IFEA’s work. As such, the proposal included plans to restructure IFEA’s executive leadership, broaden the student base to include more trainees from governments and academic centers, and place greater curricular emphasis on statistical measurement.

“Major policy decisions are being taken at present on the basis of utterly inadequate information,” warned Reynolds in the proposal. “We are in the position of bridge builders working without the physical and engineering knowledge that would tell us the strength of our materials. The problem is not merely that we have no body of tested knowledge about economic growth. It goes deeper, to the fact that we do not have the information base on which a body of principles could gradually be constructed.”

Indeed, Reynolds and his colleagues were inundated with what he called “statistical horror stories from abroad.” For example, UN statistics reported that 20 percent of Burma’s (now Myanmar’s) national income was going to new investment. “This struck me as obviously too high,” Reynolds reflected in 1960. “On inquiring, I discovered that all the country’s military expenditures are classified as investment. ‘Isn’t suppressing the guerrillas the best investment we could make?’ they said.” Such anecdotes underscored the urgent need for more rigorous training in economic measurement – and the critical role Yale’s training and research programs could play in meeting that need.

Triffin’s legacy & IDE today

EGC’s founding in 1961 helped strengthen IFEA’s training by exposing students to cutting-edge concepts and methods for economic measurement. In 1964, for instance, Brazilian IFEA student Edmar Bacha took a course on Latin American Studies while also joining a seminar on Latin America’s economic problems – connecting with Yale economics professor Carlos Diaz-Alejandro, EGC visiting scholar Celso Furtado, and fellow Latin American IFEA student Guillermo Calvo, now emeritus professor at Columbia.

Bacha (far left) on Hillhouse Avenue with IDE classmates, March 1965.

In the Latin American seminar, Diaz’s presentation of comparative research on industrial productivity in Argentina and the US inspired Bacha to “do the same exercise with Brazil instead of Argentina,” Bacha wrote to his mother. “It will be a pain to write, requiring elaboration of huge statistical series and keeping the electronic computer busy. In any case, it’s the type of training I need, because I never did this kind of econometric research.”

This kind of econometric training helped form the foundation for Bacha’s career as a prominent economist in Brazil who designed the Plano Real to curb the country’s rampant inflation.

EGC’s creation reflected a broader shift in Ford’s priorities toward PhD-level training and academic research. In 1962, the foundation asked Reynolds to justify continued support for IFEA. The program became part of a wider conversation in the development field about how – and where – foreign economists should be trained. By 1963, a consortium of American economics departments agreed that although training foreign economists in US institutions might be necessary in the short term, the long-term goal should be to develop programs abroad. Despite overwhelmingly positive feedback from alumni and their employers, Ford decided to wind down IFEA funding in favor of supporting EGC. The final grant ended in 1968.

Even so, IFEA’s track record with foreign governments and international organizations persuaded Yale to continue the program on a smaller scale under EGC, with approximately five to ten students per year. Since then, the renamed IDE ultimately expanded again – today hosting 30 to 35 students per cohort – but it has retained its intimate scale. Students benefit from Yale’s wide academic offerings while enjoying close ties to faculty, their fellow students, and a dedicated alumni network.

“The small classroom facilitates student participation, and lively discussions often continue after class,” said IDE co-director Fieler. “It’s in these discussions that students share their diverse backgrounds, previous professional experiences, as well as what they have learned in other courses or research assistantships here at Yale.”

“Our smallness is our strength,” adds IDE co-director Boozer. “IDE’s alumni are incredibly generous and giving with their time. Our alums had such an enjoyable experience in their time here that they want to stay part of this broader community.”