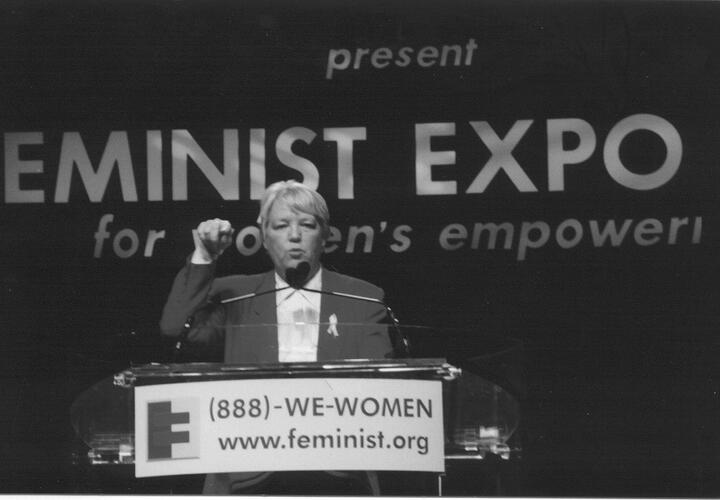

Heidi Hartmann, an early Yale Economics woman PhD, discusses how sisterhood can shape public policy

As a graduate student, she demanded an end to sexism at Yale. She has gone on to found a feminist think tank and conduct economic research that has informed policy decisions by Congress, the White House, and the Supreme Court, as well as states across the US.

Heidi Hartmann '72 M. Phil ’74 Ph.D. first caught the media’s attention in 1971 when she protested outside Mory’s, the private club near Yale campus that excluded women. In the decades since then, collective action has been a motivating principle of her research and activism.

“Organizing itself was seen as very radical and women's liberation was seen as a militant force,” Hartmann said in an EGC interview. “So, when you feel that the mainstream isn't particularly accepting of your views and ideas, you organize with like-minded people so you can develop them further.”

Since the early days of the women’s liberation movement, Hartmann has been a leading scholar of the intersections between economics, public policy, and gender. Her portfolio of research on the wage gap, paid leave programs, and women’s lifelong economic security has promoted the inclusion of women’s voices in American society.

These values led to her founding the Institute for Women's Policy Research (IWPR) in 1987 and winning the MacArthur Fellowship (commonly known as the “Genius Grant”) in 1994. She is a founding member of the International Association for Feminist Economics, which, through its journal Feminist Economics and annual conferences, has helped raise the profiles of feminist economics and women scholars around the world and within the discipline of economics.

Hartmann's portrait hangs in the Department of Economics, along with other women economists who received their PhDs from Yale.

The roots of a career in activism and academia

Hartmann was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, the child of German immigrants who divorced due to financial challenges when she was young, and she grew up in Seaside Heights and Toms River, New Jersey. Her mother struggled in low-paying jobs to take care of both Hartmann and her brother, experiences that piqued Hartmann’s interest in economics. From the start, she felt that studying economics was a way to “take care of people” on a large scale.

She dreaded sick days preventing her from going to school and was fascinated by everything from drawing and scribbling letters at the dinner table at age four to her work with graphs in economics in college.

Hartmann went on to pursue an ambitious educational path for a woman at the time: she obtained a B.A. in economics with high honors from Swarthmore College in 1967, a Master of Philosophy in economics in 1972 and Ph.D. in 1974, both from Yale.

With her atypical Ph.D. thesis topic, Capitalism and women’s work in the home, 1900-1930, it was clear that Hartmann and her career would stand out among economists of her time.

Hartmann “was bold when she needed to be,” said Francine Blau, Frances Perkins Professor of Industrial and Labor Relations and Professor of Economics at Cornell, like Hartmann one of the small minority of women entering the field of economics in the 1970s. “One of the boldest things she did was her dissertation, at a time when there wasn’t much interest in gender – the faculty certainly was not interested.”

Benefiting from, and organizing, other women at Yale

Hartmann said she never felt isolated during her time at Yale, even though there were only four women in her incoming graduate economics class. With the support of the small but close-knit community at Yale and in New Haven, which featured a strong New Left movement and women’s liberation organization, Hartmann felt inspired to act politically.

“When we were upset about anything, we would just organize a group of people together to demand something,” Hartmann chuckled. “It was a time in which lots of people were tirelessly involved in movements and it made a difference to organize.”

Until that time in 1971, Mory’s Association regularly hosted business meetings for various University departments on the upstairs floor. However, their policy prohibiting women from entering the club downstairs forced all women who attended the meetings to use the outdoor stairs.

Hartmann and women from other graduate Yale departments demanded a change. The group gathered outside the doors of Mory’s and actively engaged passersby in their cause. They challenged men who entered the club, asking “Tell me, sir, are you a racist as well as a sexist, or only a sexist?"

The graduate women in economics, including Hartmann and Janet Yellen, who today serves as the United States Secretary of the Treasury, wrote and signed a letter to the Department of Economics against the gender-based double standard, urging the department not to meet at Mory’s.

While the policy at Mory’s remained unchanged initially, Hartmann and her community succeeded in getting the Yale Department of Economics and Yale Law School to relocate their meetings. Subsequently, faced with the loss of their liquor license due to organizing by Yale Law students, Mory’s opened to female Yale undergraduates on the same terms as male undergraduates.

From feminist advocacy to applied women’s research

Hartmann continued to develop her ideas on policy, gender, and economics after graduating from Yale. She frequently participated in sessions on women in several of the annual economics conferences and, while working at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC, gathered with her female colleagues at lunches (an act which itself caused a stir).

Still, Hartmann often felt her feminist beliefs and work were misunderstood by the mainstream. According to Hartmann, many men at the time feared “women’s liberation” and even men on the political left failed to recognize it as a serious movement aiming to increase women's civil rights and economic well-being.

"Women's liberation is about sisterhood and bringing everybody together," Hartmann said. Like any successful feminist in public policy, Hartmann has managed to bring a lot of men along with her.

Hartmann knew that to create a societal change, she needed to bring women’s issues into the policy sphere. In 1987, she founded a non-profit focused on women-centered public policy research which would become known as the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR).

Hartmann and Hilda Solis, Secretary of Labor in the Obama administration, in 2012.

“Women’s policy research is still sidelined everywhere in terms of professional academic organizations,” Hartmann said. “The focus on policy research of interest to women is often a small part of larger organizations. Women’s policy research does not have an organization explicitly championing it out there besides the Institute [IWPR].”

IWPR initially faced many challenges in credibility from even the progressive movement in Washington, who saw any research about women as “advocacy,” and feminist issues overall as either too “extreme" or irrelevant for the greater policy sphere. While IWPR initially had the word “feminist” in its name, Hartmann soon changed it to “women” due to reactions from potential funders. She continued her research despite mainstream criticism.

IWPR soon became a valued voice in the policy sphere, winning its initial battle for public acceptance. Today it is one of the largest, longest-running, women-focused, policy-oriented non-profits in the United States.

“Dr. Heidi Hartmann is a living legend who ushered in a new era of women-led policy research," said Rosa DeLauro, US Congresswoman representing Connecticut’s 3rd District. "Her brainchild, the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, nurtured female thinkers and policymakers from all fields, including myself, and gave us equal footing to demonstrate that our ideas were just as grounded in data and evidence as male researchers."

Research at IWPR

One of the first publicly recognized research reports from the IWPR was Unnecessary Losses in 1990. This research showed that even unpaid family medical leave helped women because they had jobs to go back to. Many members of Congress consulted the report, especially after Hartmann testified, as they considered and ultimately passed the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, a law ensuring employees could access up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave per year without losing their jobs or health insurance.

Hartmann at a Congressional briefing on women and Social Security organized by the office of Nancy Pelosi, with Terry O’Neill, then president of the National Organization of Women (L), and Caroll Estes of the University of California, San Francisco (R).

More recently, Hartmann’s IWPR research has focused on developing simulation models of paid leave programs that benefit workers of all income levels. The paper, "Estimating Benefits: Proposed National Paid Family and Medical Leave Programs" coauthored by Jeffrey Hayes, builds upon fifteen years of research simulating family leave policies.

In 2004 and 2018, Hartmann partnered with Stephen Rose to explore the lifetime results of women's employment in segregated occupations and their resultant lower wages, finding that over a twenty-year period a typical woman earned only 50% of what a typical man earned. This research reinforced her focus on the importance of women's retirement security. With others Hartmann proposed adding caregiving credits in Social Security to increase women's (or other caregivers') benefits based on more than their earned wages.

Additional Research

Besides IWPR, from which she retired as president in 2019, Hartmann has also gained recognition for her feminist analysis of a range of theoretical and policy economic research before and after IWPR.

Her article "Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism," published in 1979, details what makes women’s issues revolutionary, how "the personal is political" for women, and how women’s issues merit collective action. It compares the relationship between Marxism and feminism to marriage law: not only do men legally dominate women in English common law on marriage, but Marxism dominates feminism by discouraging women’s independent organizing. It also discusses how inequalities in marriages mirror greater social phenomena. Not only is the article Hartmann’s most widely read and translated work, she cites it as a personal favorite.

Hartmann’s research has a history of creating a tangible social and political impact. She contributed to Women, Work, and Wages: Equal Pay for Jobs of Equal Value, a 1981 National Academy of Sciences report which exposed the pervasiveness of occupational and job segregation by sex and popularized the concept of comparable worth. The Supreme Court considered it when interpreting Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a law prohibiting employment discrimination. It also led Hartmann to testify before Congress for the first time, an act she has repeated many times since. An article Hartmann wrote in semi-retirement describes what it was like to lead IWPR as a feminist economist with roots in political economy, like feminist economics another heterodox sibling of mainstream economics.

The makings of success

For her research efforts in economics for women, Hartmann was awarded a 1994 MacArthur Fellowship.

Hartmann’s mother insisted to journalists covering news of the award that her daughter won because she was “always a hard worker,” who sat at the dinner table and did her homework independently. However, Hartmann attributes her success to her connection with others.

“Certainly, some good research ideas occur alone in the shower,” Hartmann said, “but more often progress in research on women's economic needs – and effective remedies – comes from working with others and listening to those affected by public policies.”

Hartmann is the mother of three daughters. Her husband, Jack Wells – who is also a Yale Economics PhD – served as Chief Economist at the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Like her mother, Hartmann also thinks hard work has played an important role in her success. "Persistence pays off too,” she said. “It can take years and years to see a public policy change enacted. At every step of the way, new research can make a difference."