Q&A: Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg on Poverty Reduction in an Era of Waning Globalization

The Elihu Professor of Economics at Yale and outgoing Chief Economist of the World Bank Group, returns to campus to deliver the 30th annual Kuznets Memorial Lecture.

Globalization, for all its faults, has been good to many poor people living in developing countries. Millions in East Asia have escaped the threat of hunger by leaving the fields to work in factories producing manufactured goods to sell in the West. So, what happens to the prospects of the world’s poor when the West stops buying?

Pinelopi (Penny) Koujianou Goldberg’s is the Elihu Professor of Economics at Yale, and outgoing Chief Economist of the World Bank Group. Her recent research explores the extent to which cross-border trade reduces poverty in developing countries and the effects of the current trade war with China is having on the US economy. This Thursday, Penny will deliver the 30th annual Kuznets Lecture on the subject, “Poverty Reduction in the Era of Waning Globalization” and take questions from Yale students. The event was named in honor of a cofounder of the Yale Economic Growth Center whose work also examined the interactions between growth, inequality, and poverty reduction.

Penny spoke with us about how changes in world politics affect the approach to reducing poverty – particularly in Africa – and how Kuznets’ theory itself may be affected by recent developments in a world marked by substantial inequalities.

Economic growth is often cited as the tide that will lift all boats – and China and India’s roles in reducing total world poverty are often seen as important testaments. Yet, many fast-growing Asian countries are also seeing the gap widen between the very rich and very poor. Looking ahead, how do you see the relationship between growth, inequality, and poverty evolving?

The Kuznets lecture I’m going to give aims to address some of these questions. It is true that growth is highly correlated with poverty reduction. It would be hard to deny that, even though we have examples where growth did not generate poverty reduction. Usually that happens where growth is associated with huge inequalities. There are plenty of examples, especially in African countries, where wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few. In such cases, even when the tide rises, only very few boats rise. Growth doesn’t trickle down and doesn’t improve the lot of the poor.

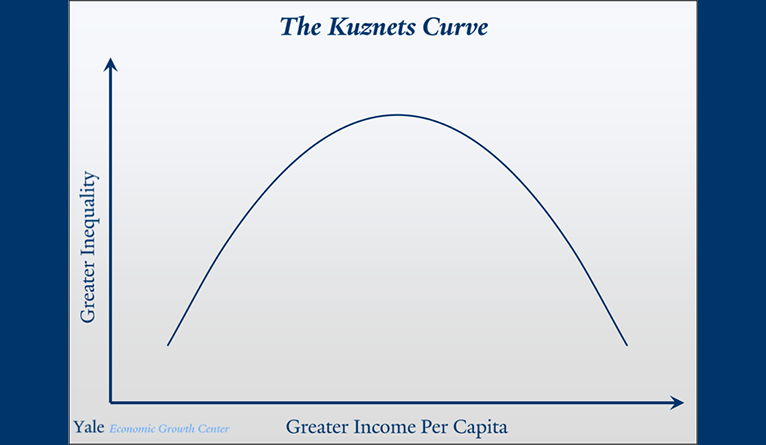

[Simon] Kuznets was most famous for the Kuznets Curve, which posits that there is a tradeoff in the early stages of development between growth and inequality. One point I want to make in the lecture is that we live at a very different time, when the world is changing rapidly, retreating from globalization. Many fear that the old model of export-led industrialization is no longer going to be relevant. And I want to make the point that in this new world, a certain degree of equality and growth may be complements and not substitutes. To put it in a different way, you cannot have growth unless you have a certain degree of equality.

First proposed by Simon Kuznets, an economics Nobel laureate who was instrumental in founding the Economic Growth Center at Yale, the Kuznets Curve posits that inequality is low both at high and low levels of income per capita, worsening to a peak during transitory growth. The path of inequality during economic growth is thus represented as following an "inverted U" path as income per capita rises.

Just last month you announced that the 2021 World Development Report will focus on “Data for Development”. How do you think these changing patterns of world poverty and inequality that you mentioned influence the ways in which we measure well-being?

First of all, measuring poverty is a huge challenge, and you don’t appreciate it fully until you come to the World Bank. There are many conceptual issues – about getting access to the data, about collecting data – but more than anything else you have the problem that countries often are not willing to share the data. You often don’t have independent statistical agencies sharing the data. So just getting the data is a huge challenge.

I don’t think the poverty data we have changed our view of how to measure wellbeing. What I think has changed more, perhaps, than attitudes isis the realization that we already live very well by conventional standards. Per-capita incomes are very high in the developed world. We have enough to eat, we have enough to drink, however, people feel increasingly unhappy, they feel under pressure, they feel huge insecurity and uncertainty about the future. They feel they don’t have enough time to spend with their family, raising their children or with their elderly parents. Most importantly, they are very concerned about the future of the planet, about climate change. And at this point you ask the question, is further growth really what we should be striving for?

Measurement there is very important because if all you care to track is, as a statistical agency, is per-capita GDP, then that becomes your only relevant measure of success. So, the push to develop more general measures of wellbeing has come from the more advanced countries, from the people who are well-off, who have realized that we need to develop a measurement approach to take all these other aspects of life into consideration. Because ultimately that’s what we care about – we care whether people feel happy and fulfilled, we don’t care about how much per-capita income they have.

So, this is a very valid position, a very valid attitude in advanced countries. It becomes more controversial when you look at developing countries, because there you have huge poverty rates, and by that, I mean extreme poverty, living on less than $1.90 a day. So there, you are talking about basic needs. In such countries, employing traditional measures is still very helpful.

It’s a sad tradeoff, but people in developing countries care less about climate change and care less about time with family, they have plenty of time with family, they do care about traditionally measured growth in order to improve their living standards.

How would you defend the benefits of trade to someone who feels that they have become poorer as a result of globalism?

This is a very good question, because economists have argued for centuries that trade is good for the economy as a whole – it is good for the aggregate. However, economists have also argued that trade generates winners and losers. So, saying that someone has lost from trade is perfectly consistent with the claim (and evidence) that the average citizen in an economy has benefitted from trade.

So, what do you say to a person who actually has lost from trade? First, I would not deny the fact that they may have lost because of trade – I would acknowledge the evidence rather than trying to discredit it as some do. Second, I would tell them that the proper response is not to shut down trade. The proper response is to try to compensate those who were impacted negatively by trade. One of the big insights that economists have provided is that there are sufficient gains generated by open trade that the winners can compensate the losers and still be better off. That is the concept of what we call “Pareto improvement” in economics. So, when people think they lost from trade, what they should push hard for is compensation and redistribution, not closing off the economy and returning to protectionism.

The proper response is not to shut down trade. The proper response is to try to compensate those who were impacted negatively by trade. – Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg

You have just returned from a trip to Kenya. There seems to be growing consensus that the methods that worked in China to spur growth and reduce poverty won’t work in Africa. Have you seen promising ideas for what can work?

Again, this is something I’m going to talk about in the lecture. I think we’re at a point in time when we need a new vision, or a new model of what might work in places like Africa, and I’m afraid at this point, there’s no consensus of what this vision is.

My personal view is that Africa needs to rely on itself more than ever. The idea that export-led industrialization as it happened in China or east Asia is going to lead growth in Africa becomes less and less plausible as time goes by, for many reasons. Protectionism is on the rise – industrialized countries are less open to imports from developing countries. In addition, there is by now a lot of competition, so there is Kenya, there is Ethiopia, there is Bangladesh, there is Vietnam, there are many countries competing in this space. There are also new technologies and automation threatening low-wage jobs – the traditional comparative advantage of developing countries.

On the other hand, the African market is a very large market with incredible potential. It has not been developed yet. So, regional integration might be one path forward. Rather than opting for global integration, which may be very hard to achieve these days when countries are retreating from multilateralism, it might be more feasible to push for regional trade agreements and create bigger regional markets for countries’ goods and services.

We are still a very long way from there because most counties are averse to this idea – they see their neighbors as competitors rather than countries they can cooperate with. So, more than anything else, we need a big change in mindset, we need policy makers to embrace the idea of regional cooperation.

And as I will argue in the Kuznets lecture, we need countries to push for a more equitable distribution of resources within their borders. If trade with rich countries is no longer the engine of growth, it will be more important than ever to rely on the domestic resources, and particularly the domestic market power generated by a healthy middle class, to generate growth that does trickle down and translates to poverty reduction.

What has the shift from an academic to a policy position been like?

Taking a policy position is a very interesting and rewarding experience, and it’s something I would recommend that every academic does from time to time.

There are three big differences between policy and academia. The first is that you get exposed to questions you’re not exposed to as an academic. Or, in some cases, you’re exposed to these questions much earlier than academics – usually the questions come to academics with a lag of months if not years. So, you are on the front line and you know what’s really relevant. That comes with a drawback, which is the second big difference: policymakers need answers right now! In academia, we strive to give the most rigorous answer possible, so we take the time to collect and analyze the data and provide robust evidence. As a policymaker you don’t have this luxury, so you often have to give advice based on your best judgement. A third difference, that I truly appreciate now, is that in academia we have the freedom to say what we really think. You have many more constraints when you enter policy.