Economist Dudley Seers used time at Yale in the 1960s to reimagine international development

In the early 1960s, Seers brought iconoclastic ideas to the EGC as a visiting scholar — and wrote seminal papers that still resonate today.

What is development economics? Several decades after its emergence as an academic discipline, this question still inspires spirited debate. While the prevailing orthodoxy continues to evolve, certain thinkers and their ideas have proved enduring. One such pioneer was Dudley Seers, a British economist whose insights about the development process were far ahead of their time. In the early 1960s, Seers was a visiting fellow at Yale’s Economic Growth Center (EGC), where he produced two landmark papers that still resonate today.

Helping shape a nascent field

Both as an academic and policymaker, Seers played an important role in the early history of development economics. Born in 1920 and trained at Cambridge, he spent much of his career studying what were then called “Third World” countries. In the 1950s and 1960s, he worked for the UN economic commissions for Latin America and Africa, traveling extensively throughout both regions. In 1964, he helped found the UK’s Ministry of Overseas Development, and in 1967 became the founding director of the Institute for Development Studies at the University of Sussex.

Professional portrait of Dudley Seers. Photo courtesy of Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

During this period, development economists were split between two competing schools of thought: neoclassical economics and structuralism. The neoclassical approach emphasized supply and demand and utility maximization as its organizing principles, believing that these forces will help allocate resources efficiently in any free market economy. Structuralism, by contrast, emphasized country-specific analysis to identify an economy’s key structural relationships, such as factor endowments or trade links with the global economy.

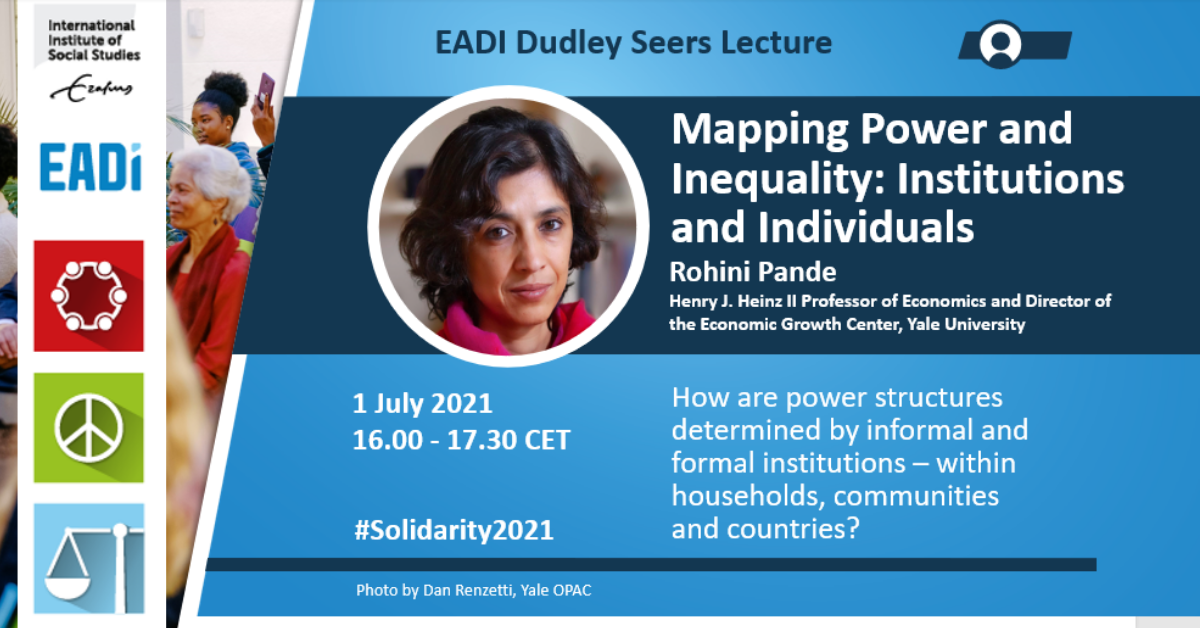

The Dudley Seers Memorial Lecture

Rohini Pande delivered a lecture, "Mapping Power and Inequality: Institutions and Individuals" on July 1, 2021, hosted by the European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes (EADI).

Seers was a staunch structuralist, arguing that development economists should focus on poverty, inequality, and unemployment in addition to topline measures like GDP per capita growth. But by his death in 1983, the neoclassical school was on the ascent. During the Cold War, development economists in the West had begun favoring free-market, private sector-led growth strategies. In the 1980s and 1990s, these approaches coalesced into the Washington Consensus, which prioritized a standard policy regimen of low inflation, balanced budgets, free trade, and privatization. But by the early 2000s, many contested the Washington Consensus, and argued that economic development was a far more complex process.

Today, development economics is a diverse blend of structuralist and neoclassical approaches, prioritizing country-level analysis and a broad set of goals, from growth to poverty reduction, social development, anti-corruption, and promoting the rule of law. It is also marked by significant engagement of researchers with the design of development policy, often based on insights gathered through field experiments.

Sixty years ago, Seers anticipated many of these intellectual developments. In fact, several of his most enduring insights were cultivated at Yale – from 1962 to 1964, he was one of EGC’s first visiting fellows. During his time on campus, he actively engaged in debates about the future of development economics, earning a reputation for being provocative and iconoclastic. He was also prolific, writing at least eight papers during his time in New Haven.

Two of these papers, in particular, exemplify Seers’ pioneering insights: “The Limitations of the Special Case” and “Why Visiting Economists Fail.”

An early champion of “context matters”

A central critique in “The Limitations of the Special Case” is one that may seem obvious today: poor economies are very different than rich ones, and they require different policies to promote growth and development. But this was a radical idea in 1963, when many considered economics principles to be universal. As Seers points out, though, economics was designed in and for industrialized countries – namely by British and American economists, seeking to better understand and analyze the US and UK economies.

The problem, Seers writes, is that developed industrial economies are “by no means typical”:

Viewed from the point of view of either history or geography, it is an extremely rare case, and obviously so. There have been only a few such economies for a few decades; even now they cover only quite a small fraction of mankind… The typical case is a largely unindustrialised economy, the foreign trade of which consists essentially in selling primary products for manufactures. There are about 100 identifiable economies of this sort, covering the great majority of the world’s population.

Seers lays out the set of structural characteristics that make industrialized countries so unique, from their highly-educated and skilled populations to their diversified sectors, large public revenue bases, and deep capital markets. As Seers notes, the majority of countries in the world lack these characteristics – and have many of their own unique structural challenges, from geographic barriers to export dependency, as well as political and social issues. Seers contends that it is naive and dangerous to apply industrialized-country models onto non-industrialized economies. The prevailing orthodoxy, he argues, is inappropriate and insufficient for analyzing and understanding the process and challenge of development.

Written in an era when development economics was barely mentioned in textbooks or featured in economics departments, the paper laments that economics students of the day were completely unprepared to study poor countries. “People are being turned out as economists,” Seers writes, “who can draw diagrams illustrating the theory of duopoly, but who would not know how to start dealing with the question (say) of whether a steel industry should be established in Guatemala, or what it should make or how much.”

An early critic of “best practices”

In “Why Visiting Economists Fail,” these themes are extended to the pitfalls of providing economic advice to developing country governments – an endeavor Seers participated in often but that, he admits, typically fails. “In the ministries of almost any underdeveloped country,” he writes, “you can find cupboards full of the reports of economists, reports which have been talked about for a week or two, then put away and forgotten.”

By considering why these failures are so common, however, Seers generates important insights about the challenge of putting development economics into practice. He notes, for instance, that developing countries often have weak statistics, making it nearly impossible to conduct rigorous data analysis or construct meaningful economic models. Likewise, policy instruments that are widely used in industrialized economies, such as monetary policy, might have significantly less effect in developing countries. Visiting economists also often encounter difficult political dynamics, from unreceptive “host” governments to dysfunctional institutions.

More broadly, the paper underscores how challenging it can be for short-term visitors to understand the full complexity of a developing country’s economy, society, and politics. He notes that many economists, when faced with this challenge, may fall back on industrialized-country models. As if anticipating Washington Consensus policy prescriptions, he writes that short-term visiting economists may make the “grotesque error of handing out sweeping recommendations that derive rather from ideological bias than from study of the local problem… such as ‘balance the budget,’ ‘control imports,’ or ‘unify the exchange rates.’”

The paper is not entirely cynical, however. Seers notes that the mere presence of a visiting economist can have a positive impact, either by encouraging junior officials or improving government statistics by requesting data. And he underscores, importantly, that “a visitor can achieve a great deal merely by asking the right sort of question.”

What is development economics?

Beyond the influence of his papers, Seers also had a lasting impact on the students and professors he met at Yale. Donald Mead, a PhD student at the time and now Professor Emeritus at Michigan State University, still vividly remembers the visiting scholar. “A lot of us were seeking to make sense of the development process,” Mead said. “We sat at his feet, listened, debated, and learned a lot.”

Seers also played a role in shaping the EGC’s future. Around the time of his visit, EGC created its Country Studies program, which funded young economists to spend 1-2 years in a developing country, gathering data and conducting applied country-level research – two goals that Seers, despite his critique of visiting economists, would have surely supported.

Development economics has evolved considerably during the last sixty years. But in some respects, the field is still grappling with many of the tensions Seers identified. The persistence of contemporary debates – between promoting growth or reducing poverty, balancing normative assumptions, or the relative merits of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) – suggests that tension may be inherent to the field.

Indeed, perhaps tensions are the drivers of progress. In 1963, Seers surveyed the challenges facing developing countries and called for the complete “reconstruction of economics” – because “the existing body of theory cannot explain what has to be explained.” In a world still riven with poverty, conflict, and uncertainty, such a revolutionary spirit can be instructive.

Greg Larson is a consultant and writer focused on economics, public policy, and social impact. We thank former EGC intern Christina Pao for extensive editorial and research assistance on this article.

This article is part of a series about the first decade of the Economic Growth Center, published as part of EGC’s 60th Anniversary celebration during 2021.