Expanding the scope of India's Covid-19 relief measures

An April 2020 survey conducted by a team of researchers finds that India's food distribution system helps alleviate food insecurity and should continue given forecasts of continued pandemic-related distress.

Background

On March 24, the Government of India introduced a ₹ 1.7 trillion ($23 billion) relief package to mitigate the economic effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Relief measures included transferring cash to government-provided digital bank accounts and providing food rations through the country’s public distribution system (PDS). India’s PDS provides food and other essential items to the poor at subsidized prices through a network of ration shops.

Analysis

- A survey of state-owned shops shows that the Indian state of Chhattisgarh is successfully implementing India’s public distribution system (PDS) for food relief. Very few PDS shops were closed (1%), had inadequate supplies of rice and salt (1-8% depending on the food item), had not instituted at least one social distancing measure (less than 1%), or were not complying with free rice allotments for citizens (1%).

- A survey of rural women supports the PDS survey findings, but food security remains an issue. 95% of respondents reported receiving rations from the PDS shop and 98% reported that rice was available and was free. However, a third of households worried they would run out of food or would need to cut down on the amount of food consumed.

- Women working in rural childcare centers report that current rations do not fulfill nutritional needs. Although PDS shops stock enough rice and salt, some women said that they had lower access to fruit and vegetables compared to other districts (13% of respondents), a lack of cheap replacements for green vegetables (27%), and the following health concerns in the community (21%): feeling weak, loss of appetite, weight loss, and feeling increasingly irritated. Over a quarter of women reported eating more rice and lentils compared to what they ate prior to lockdown.

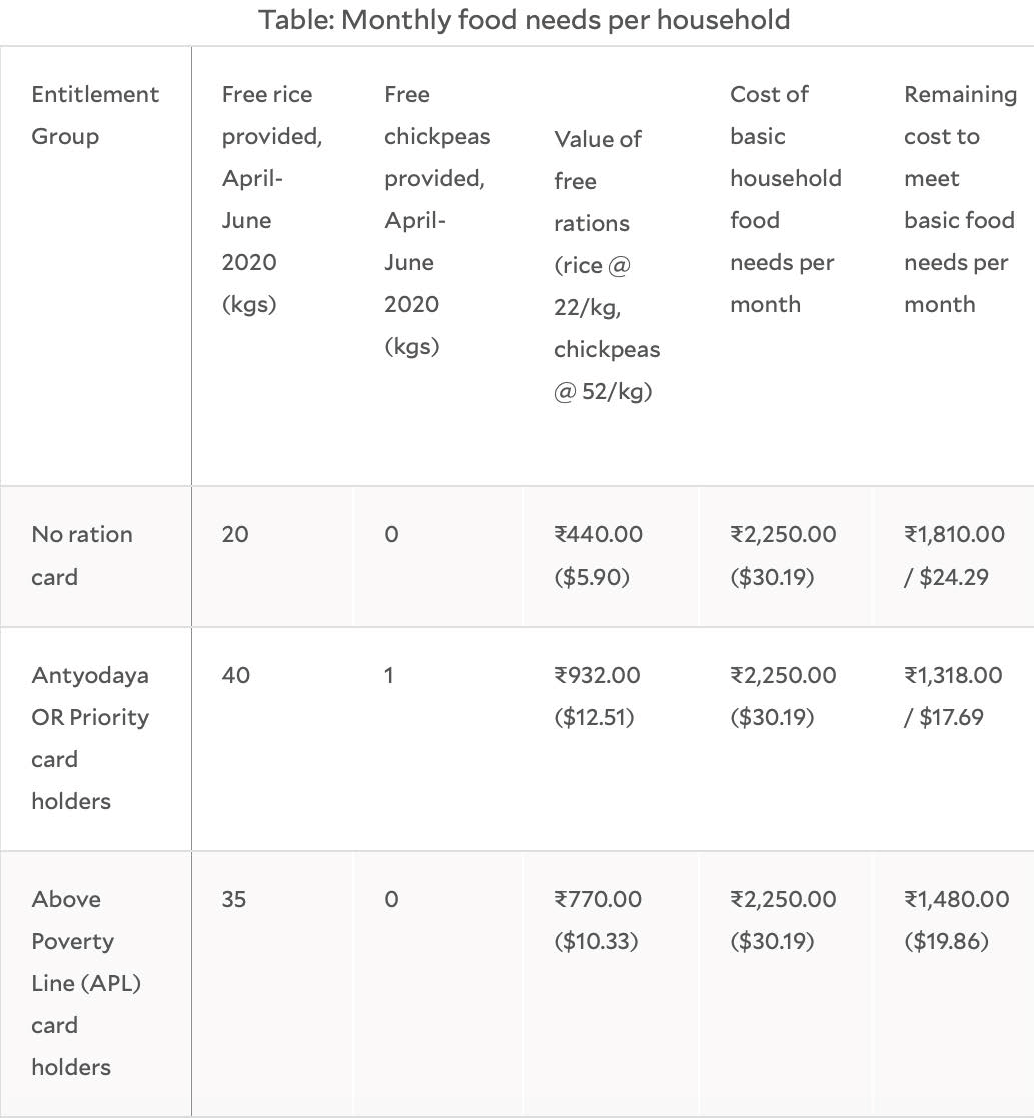

- Current rations and digital cash transfers cannot fully meet the caloric needs of the poor. While relief measures help, without a way to earn other income, the poorest rural households will still require between ₹ 1,480 and 1,810 ($19.86 and 24.29) to cover basic monthly needs. Moreover, 51% of surveyed rural women reported not receiving the cash transfer.

Looking Ahead: Expanding PDS

At the time of writing, India’s government is providing extra rice (5 kg) and lentils (1 kg) – a policy that was scheduled to end after an initial three-month period, but which has been extended. Given forecasts of continued distress during the Covid-19 crisis, the extra rations may continue to mitigate food insecurity and stabilize food prices in the private market.

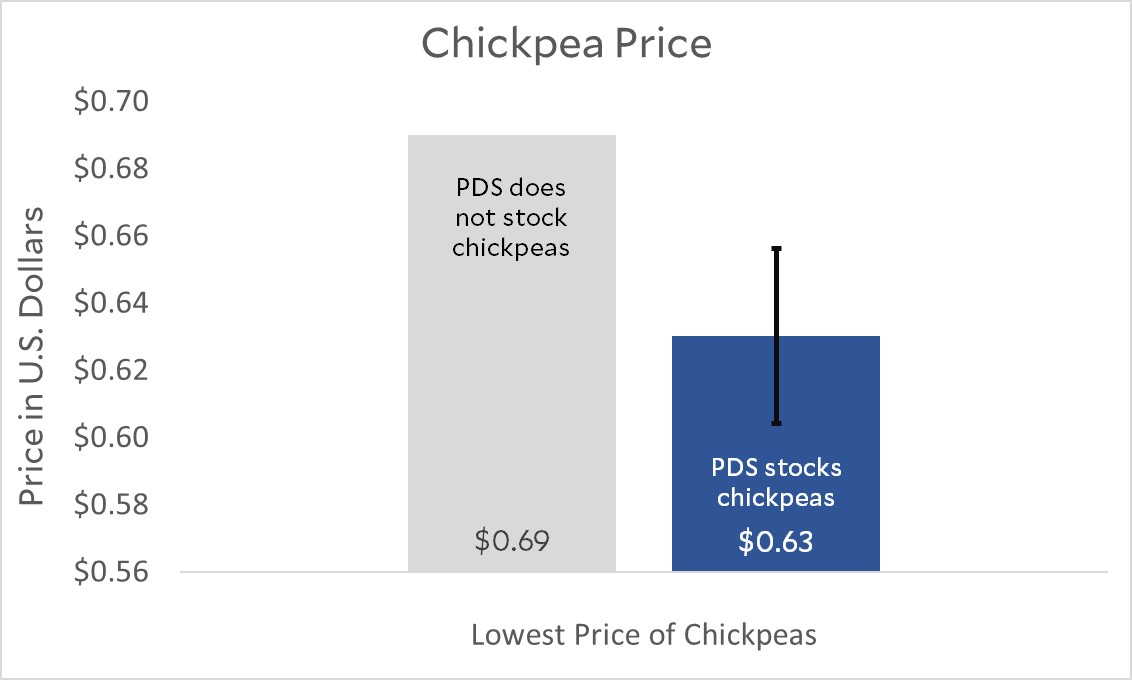

Prices for chickpeas in private shops are lower in villages where the PDS shops stock them than those in villages where they don’t.

Stocking PDS shops with other goods including beans, peas, lentils, and edible oils may help meet a wider array of nutritional needs and stabilize food prices in private shops. Prior research has shown that the PDS helps insulate poor households from spikes in food prices by giving them access to price-stabilized rations, and data from the Chhattisgarh PDS survey suggest that this may be the case here.

The Government of Chhattisgarh collects most data digitally, allowing it to respond rapidly to changes in local conditions. In fact, the areas of the state that are least well-functioning are those that do not keep digital records. The research team worked with the government to feed this data into an online dashboard, which can facilitate further decision-making and identify kinks in the system, such as the number of shops that did not distribute any rice in March. Other Indian states could adopt digital processes as a way to increase the efficiency of their PDS systems.

About the Surveys

Our research team analyzed the efficacy of these economic interventions through four data sources:

- a survey of food availability covering 4,000 state-owned and 28,000 privately owned shops in the state of Chhattisgarh

- surveys of 3,951 rural women

- administrative food distribution shop data from the Indian government and

- in-depth telephone interviews of 15 women working in rural childcare centers.

This was a collaborative effort by researchers from Yale Economic Growth Center, Yale MacMillan Center, Harvard Business School, the University of Southern California Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research, Warwick Business School, and LEAD at Krea University.